Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

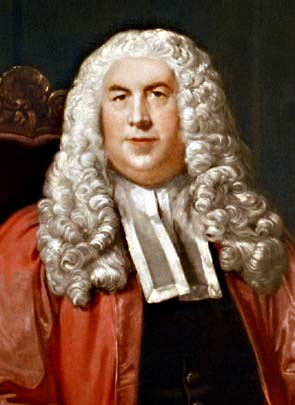

William Blackstone, fully Sir William Blackstone

English Judge, Jurist and Tory Politician most noted for writing The Commentaries on the Laws of England

"Law is the embodiment of the moral sentiment of the people."

"The suicide is guilt of a double offence; one spiritual, in invading the prerogative of the Almighty... the other temporal, against the king."

"If [the legislature] will positively enact a thing to be done, the judges are not at liberty to reject it, for that were to set the judicial power above that of the legislature, which would be subversive of all government."

"In all tyrannical governments the supreme magistracy, or the right both of making and of enforcing the laws, is vested in one and the same man, or one and the same body of men; and wherever these two powers are united together, there can be no public liberty."

"It is better that ten guilty escape than one innocent suffer."

"Man was formed for society and is neither capable of living alone, nor has the courage to do it."

"No enactment of man can be considered law unless it conforms to the law of God"

"So great moreover is the regard of the law for private property, that it will not authorize the least violation of it; no, not even for the general good of the whole community"

"The husband and wife are one, and that one is the husband."

"The law, which restrains a man from doing mischief to his fellow citizens, though it diminishes the natural, increases the civil liberty of mankind."

"The public good is in nothing more essentially interested than in the protection of every individual's private rights."

"The Royal Navy of England hath ever been its greatest defense and ornament; it is its ancient and natural strength; the floating bulwark of the island."

"Those rights, then, which God and nature have established, and are therefore called natural rights, such as life and liberty, need not the aid of human laws to be more effectually invested in every man than they are; neither do they receive any additional strength when declared by the municipal laws to be inviolate. On the contrary, no human legislature has power to abridge or destroy them, unless the owner shall himself commit some act that amounts to a forfeiture."

"A second offence is that of heresy, which consists not in a total denial of Christianity, but of some of its essential doctrines, publicly and obstinately avowed."

"All presumptive evidence of felony should be admitted cautiously; for the law holds, that it is better that ten guilty persons escape, than that one innocent suffer."

"All the several pleas and excuses, which protect the committer of a forbidden act from the punishment which is otherwise annexed thereto, may be reduced to this single consideration, the want or defect of will. An involuntary act, as it has no claim to merit, so neither can it induce any guilt: the concurrence of the will, when it has its choice either to do or to avoid the fact in question, being the only thing that renders human actions either praiseworthy or culpable. Indeed, to make a complete crime, cognizable by human laws, there must be both a will and an act."

"An involuntary act, as it has no claim to merit, so neither can it induce any guilt; the concurrence of the will, when it has its choice to do or to avoid the fact in question, being the only thing that renders human actions either praiseworthy or culpable."

"And, lastly, to vindicate these rights, when actually violated and attacked, the subjects of England are entitled, in the first place, to the regular administration and free course of justice in the courts of law; next to the right of petitioning the king and parliament for redress of grievances; and, lastly, to the right of having and using arms for self-preservation and defense."

"Aristotle himself has said, speaking of the laws of his own country, that jurisprudence, or the knowledge of those laws, is the principal and most perfect branch of ethics."

"But that a science, which distinguishes the criterions of right and wrong; which teaches to establish the one, and prevent, punish, or redress the other; which employs in its theory the noblest faculties of the soul, and exerts in its practice the cardinal virtues of the heart; a science, which is universal in its use and extent, accommodated to each individual, yet comprehending the whole community; that a science like this should ever have been deemed unnecessary to be studied in an university, is matter of astonishment and concern."

"Considering the Creator only as a being of infinite power, he was able unquestionably to have prescribed whatever laws he pleased to his creature, man, however unjust or severe. But, as he is also a being of infinite wisdom, he has laid down only such laws as were founded in those relations of justice that existed in the nature of things antecedent to any positive precept. These are the eternal immutable laws of good and evil, to which the Creator himself, in all his dispensations, conforms; and which he has enabled human reason to discover, so far as they are necessary for the conduct of human actions."

"Every wanton and causeless restraint of the will of the subject, whether practiced by a monarch, a nobility, or a popular assembly, is a degree of tyranny."

"Free men have arms; slaves do not."

"Gaming is a kind of tacit confession that the company engaged therein do in general exceed the bounds of their respective fortunes, and therefore they cast lots to determine upon whom the ruin shall at present fall, that the rest may be saved a little longer."

"Herein indeed consists the excellence of the English government, that all parts of it form a mutual check upon each other."

"Human legislators have, for the most part, chosen to make the sanction of their laws rather vindicatory than remuneratory, or to consist rather in punishments than in actual particular rewards."

"I think it an undeniable position, that a competent knowledge of the laws of that society in which we live, is the proper accomplishment of every gentleman and scholar; an highly useful, I had almost said essential, part of liberal and polite education. And in this I am warranted by the example of ancient Rome; where, as Cicero informs us, the very boys were obliged to learn the twelve tables by heart, as a carmen necessarium, or indispensable lesson, to imprint on their tender minds an early knowledge of the laws and constitution of their country."

"In general, all mankind will agree that government should be reposed in such persons in whom these qualities are most likely to be found the perfection of which is among the attributes of Him who is emphatically styled the Supreme Being; the three great requisites, I mean, of wisdom, of goodness, and of power: wisdom, to discern the real interest of the community; goodness, to endeavour always to pursue that real interest; and strength, or power, to carry this knowledge and intention into action. These are the natural foundations of sovereignty, and these are the requisites that ought to be found in every well-constituted frame of government."

"In this distinct and separate existence of the judicial power, in a peculiar body of men, nominated indeed, but not removable at pleasure, by the crown, consists one main preservative of the public liberty; which cannot subsist long in any state, unless the administration of common justice be in some degree separated both from the legislative and the also from the executive power. Were it joined with the legislative, the life, liberty, and property of the subject would be in the hands of arbitrary judges, whose decisions would be then regulated only by their own opinions, and not by any fundamental principles of law; which, though legislators may depart from, yet judges are bound to observe. Were it joined with the executive, this union might soon be an overbalance for the legislative. For which reason... effectual care is taken to remove all judicial power out of the hands of the king's privy council; who, as then was evident from recent instances might soon be inclined to pronounce that for law, which was most agreeable to the prince or his officers. Nothing therefore is to be more avoided, in a free constitution, than uniting the provinces of a judge and a minister of state."

"Law, in its most general and comprehensive sense, signifies a rule of action; and is applied indiscriminately to all kinds of action, whether animate, or inanimate, rational or irrational. Thus we say, the laws of motion, of gravitation, of optics, or mechanics, as well as the laws of nature and of nations. And it is that rule of action, which is prescribed by some superior, and which the inferior is bound to obey."

"Man was formed for society; and, as is demonstrated by the writers on the subject, is neither capable of living alone, nor indeed has the courage to do it. However, as it is impossible for the whole race of mankind to be united in one great society, they must necessarily divide into many, and form separate states, commonwealths, and nations, entirely independent of each other, and yet liable to a mutual intercourse."

"Man... must necessarily be subject to the laws of his Creator, for he is entirely a dependent being...And, consequently, as man depends absolutely upon his Maker for everything, it is necessary that he should in all points conform to his Maker's will."

"Men was formed for society, and is neither capable of living alone, nor has the courage to do it."

"No outward doors of a man's house can in general be broken open to execute any civil process; though in criminal cases the public safety supersedes the private."

"Of crimes injurious to the persons of private subjects, the most principal and important is the offense of taking away that life, which is the immediate gift of the great creator; and which therefore no man can be entitled to deprive himself or another of, but in some manner either expressly commanded in, or evidently deducible from, those laws which the creator has given us; the divine laws, I mean, of either nature or revelation."

"Outrageous penalties, being seldom or never inflicted, are hardly known to be law by the public; but that rather aggravates the mischief by laying a snare for the unwary."

"Self-defense is justly called the primary law of nature, so it is not, neither can it be in fact, taken away by the laws of society."

"Such, among others, are these principles: that we should live honestly, should hurt nobody, and should render to every one his due; to which three general precepts Justinian has reduced the whole doctrine of law."

"That the king can do no wrong is a necessary and fundamental principle of the English constitution."

"The absolute rights of man, considered as a free agent, endowed with discernment to know good from evil, and with power of choosing those measures which appear to him to be most desirable, are usually summed up in one general appellation, and denominated the natural liberty of mankind. This natural liberty consists properly in a power of acting as one thinks fit, without any restraint or control, unless by the law of nature: being a right inherent in us by birth, and one of the gifts of God to man at his creation, when he endowed him with the faculty of freewill. But every man, when he enters into society, gives up a part of his natural liberty, as the price of so valuable a purchase; and, in consideration of receiving the advantages of mutual commerce, obliges himself to conform to those laws, which the community has thought proper to establish."

"The founders of the English laws have with excellent forecast contrived, that no man should be called to answer to the king for any capital crime, unless upon the preparatory accusation of twelve or more of his fellow subjects, the grand jury: and that the truth of every accusation, whether preferred in the shape of indictment, information, or appeal, should afterwards be confirmed by the unanimous suffrage of twelve of his equals and neighbors, indifferently chosen, and superior to all suspicion. So that the liberties of England cannot but subsist, so long as this palladium remains sacred and inviolate, not only from all open attacks, (which none will be so hardy as to make) but also from all secret machinations, which may sap and undermine it; by introducing new and arbitrary methods of trial, by justices of the peace, commissioners of the revenue, and courts of conscience. And however convenient these may appear at first, (as doubtless all arbitrary powers, well executed, are the most convenient) yet let it be again remembered, that delays, and little inconveniences in the forms of justice, are the price that all free nations must pay for their liberty in more substantial matters; that these inroads upon this sacred bulwark of the nation are fundamentally opposite to the spirit of our constitution; and that, though begun in trifles, the precedent may gradually increase and spread, to the utter disuse of juries in questions of the most momentous concern."

"The king never dies."

"The king, moreover, is not only incapable of doing wrong, but even of thinking wrong: he can never mean to do an improper thing: in him is no folly or weakness."

"The liberty of the press is indeed essential to the nature of a free state: but this consists in laying no previous restraints upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published. Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public: to forbid this, is to destroy the freedom of the press: but if he publishes what is improper, mischievous, or illegal, he must take the consequence of his own temerity."

"The royal navy of England has ever been its greatest defense and ornament; it is its ancient and natural strength; the floating bulwark of the island."

"The sciences are of a sociable disposition, and flourish best in the neighborhood of each other; nor is there any branch of learning but may be helped and improved by assistance drawn from other arts."

"The two idioms [English and Norman] have mutually borrowed from each other."

"There is nothing which so generally strikes the imagination, and engages the affections of mankind, as the right of property; or that sole and despotic dominion which one man claims and exercises over the external things of the world, in total exclusion of the right of any other individual in the universe. And yet there are very few, that will give themselves the trouble to consider the original and foundation of this right."

"This appellation of parson [persona ecclesi‘], however depreciated by clownish and familiar use, is the most legal, most beneficial, and most honourable title which a parish priest can enjoy."

"Time whereof the memory of man runneth not to the contrary."