Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

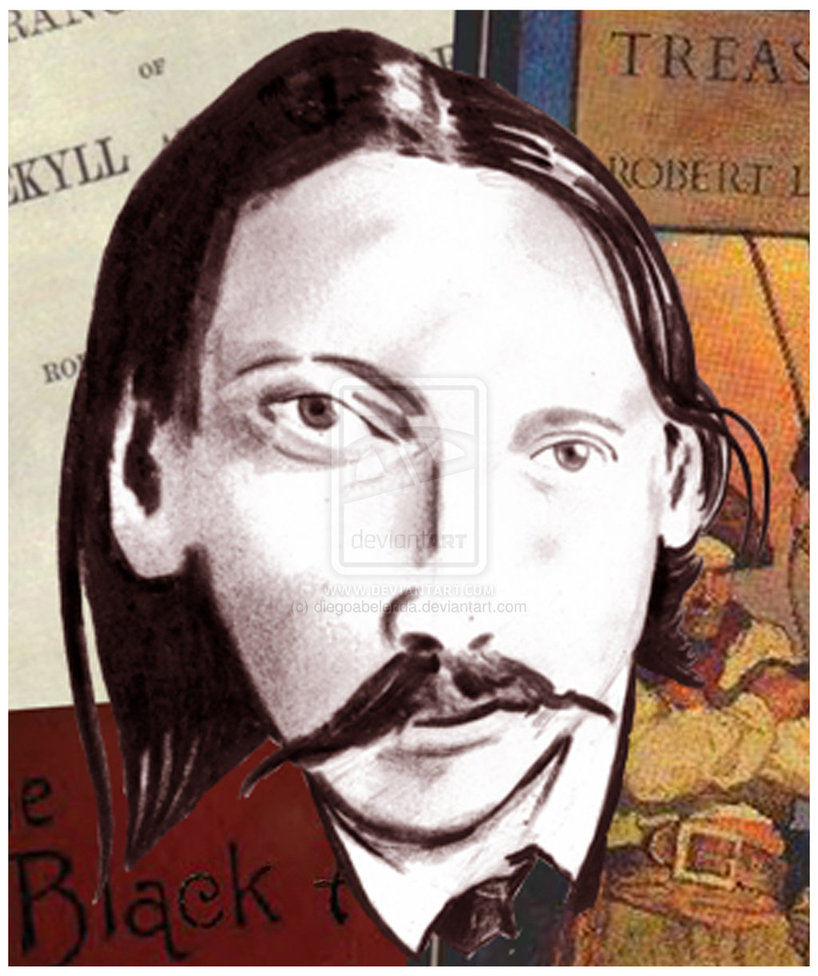

Robert Louis Stevenson, fully Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson

Scottish Novelist, Poet, Essayist and Travel Writer, known books include Treasure Island, Kidnapped, and the Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

"Everyone lives by selling something, whatever be his right to it."

"Everyone should always have two books with him, one to read and one to write in."

"Everyone who got where he is had to begin where he was."

"Everyone, at some time or another, sits down to a banquet of consequences."

"Extreme busyness is a symptom of deficient vitality, and a faculty for idleness implies a catholic appetite and a strong sense of personal identity."

"Extreme busyness, whether at school, or college, kirk or market, is a symptom of deficient vitality; and a faculty for idleness implies a catholic appetite and a strong sense of personal identity."

"Falling in love is the one illogical adventure, the one thing of which we are tempted to think as supernatural, in our trite and reasonable world. The effect is out of all proportion with the cause. Two persons, neither of them, it may be, very amiable or very beautiful, meet, speak a little, and look a little into each other's eyes. That has been done a dozen or so of times in the experience of either with no great result. But on this occasion all is different. They fall at once into that state in which another person becomes to us the very gist and center-point of God's creation, and demolishes our laborious theories with a smile; in which our ideas are so bound up with the one master-thought that even the trivial cares of our own person become so many acts of devotion, and the love of life itself is translated into a wish to remain in the same world with so precious and desirable a fellow-creature."

"Fate and the responsibility for our lives take forever linked to our backs; and when someone tries to get rid of them, do nothing but fall over with a tremendous force and unknown"

"Fear is the strong passion; it is with fear that you must trifle, if you wish to taste the intensest joys of living."

"Fiction is to the grown man what play is to the child; it is there that he changes the atmosphere and tenor of his life."

"Fifteen men on the dead man's chest ? Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum! Drink and the devil had done for the rest ? Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!"

"Find out where joy resides, and give it a voice far beyond singing. For to miss the joy is to miss all."

"For I think we may look upon our little private war with death somewhat in this light. If a man knows he will sooner or later be robbed upon a journey, he will have a bottle of the best in every inn, and look upon all his extravagances as so much gained upon thieves....So every bit of brisk living, and above all when it is healthful, is just so much gained upon the wholesale filcher, death. We shall have the less in our pockets, the more in our stomachs, when he cries stand and deliver."

"For marriage is like life in this?that it is a field of battle, and not a bed of roses."

"For my part, I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel's sake. The great affair is to move. Give me the young man who has brains enough to make a fool of himself."

"For no man lives in the external truth among salts and acids, but in the warm, phantasmagoric chamber of his brain, with the painted windows and the storied wall."

"For thirty years, he said, I've sailed the seas and seen good and bad, better and worse, fair weather and foul, provisions running out, knives going, and what not. Well, now I tell you, I never seen good come o' goodness yet. Him as strikes first is my fancy; dead men don't bite; them's my views?amen, so be it."

"Gentleness and cheerfulness, these come before all morality; they are the perfect duties."

"Give me the young man who has brains enough to make a fool of himself."

"Go, little book, and wish to all flowers in the garden, meat in the hall, a bin of wine, a spice of wit, a house with lawns enclosing it, a living river by the door, a nightingale in the sycamore?"

"God, if this were enough, that I see things bare to the buff."

"Half a capital and half a country town, the whole city leads a double existence; it has long trances of the one and flashes of the other; like the king of the Black Isles, it is half alive and half a monumental marble."

"Half an hour from now, when I shall again and forever rein due that hated personality, I know how I shall sit shuddering and weeping in my chair, or continue, with the most strained and fear-struck ecstasy of listening, to pace up and down this room (my last earthly refuge) and give ear to every sound of menace. Will Hyde die upon the scaffold? or will he find the courage to release himself at the last moment? God knows; I am careless; this is my true hour of death, and what is to follow concerns another than myself. Here, then, as I lay down the pen, and proceed to seal up my confession, I bring the life of that unhappy Henry Jekyll to an end."

"Happiness and goodness, according to canting moralists, stand in the relation of effect and cause. There was never anything less proved or less probable: our happiness is never in our own hands; we inherit our constitution; we stand buffet among friends and enemies; we may be so built as to feel a sneer or an aspersion with unusual keenness and so circumstanced as to be unusually exposed to them; we may have nerves very sensitive to pain, and be afflicted with a disease very painful. Virtue will not help us, and it is not meant to help us."

"Happy thought. The world is so full of a number of things, I'm sure we should all be as happy as kings."

"He began to understand what a wild game we play in life; he began to understand that a thing once done cannot be undone nor changed by saying I am sorry!"

"He felt ready to face the devil, and strutted in the ballroom with the swagger of a cavalier."

"He had hobbled down there that morning,"

"He is not easy to describe. There is something wrong with his appearance; something displeasing, something downright detestable. I never saw a man I so disliked, and yet I scarce know why. He must be deformed somewhere; he gives a strong feeling of deformity, although I couldn?t specify the point. He?s an extraordinary-looking man, and yet I really can name nothing out of the way. No, sir; I can make no hand of it; I can?t describe him. And it?s not want of memory; for I declare I can see him this moment."

"He put the glass to his lips, and drank at one gulp. A cry followed; he reeled, staggered, clutched at the table and held on, staring with injected eyes, gasping with open mouth; and as I looked there came, I thought, a change?he seemed to swell?his face became suddenly black and the features seemed to melt and alter?and at the next moment, I had sprung to my feet and leaped back against the wall, my arm raised to shield me from that prodigy, my mind submerged in terror. 'O God!' I screamed, and 'O God!' again and again; for there before my eyes?pale and shaken, and half fainting, and groping before him with his hands, like a man restored from death?there stood Henry Jekyll!"

"He recollected his courage."

"He sows hurry and reaps indigestion."

"He stands unshook from age to youth."

"He travels best that knows when to return. Middleton for my part, I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel's sake. The great affair is to move."

"He was a very silent man by custom. All day he hung round the cove or upon the cliffs with a brass telescope; all evening he sat in a corner of the parlor next the fire and drank rum and water very strong. Mostly he would not speak when spoken to, only look up sudden and fierce and blow through his nose like a fog-horn; and we and the people who came about our house soon learned to let him be. Every day when he came back from his stroll he would ask if any seafaring men had gone by along the road. At first we thought it was the want of company of his own kind that made him ask this question, but at last we began to see he was desirous to avoid them. When a seaman did put up at the Admiral Benbow (as now and then some did, making by the coast road for Bristol) he would look in at him through the curtained door before he entered the parlor; and he was always sure to be as silent as a mouse when any such was present. For me, at least, there was no secret about the matter, for I was, in a way, a sharer in his alarms. He had taken me aside one day and promised me a silver four-penny on the first of every month if I would only keep my "weather-eye open for a seafaring man with one leg" and let him know the moment he appeared. Often enough when the first of the month came round and I applied to him for my wage, he would only blow through his nose at me and stare me down, but before the week was out he was sure to think better of it, bring me my four-penny piece, and repeat his orders to look out for "the seafaring man with one leg.""

"He was breaking his fast on white wine and raw onions, in order to keep up the character of martyr, I conclude."

"He was in that humor when a man will cut off his nose to spite his face"

"He was only once crossed, and that was towards the end, when my poor father was far gone in a decline that took him off. Dr. Livesey came late one afternoon to see the patient, took a bit of dinner from my mother, and went into the parlor to smoke a pipe until his horse should come down from the hamlet, for we had no stabling at the old Benbow. I followed him in, and I remember observing the contrast the neat, bright doctor, with his powder as white as snow and his bright, black eyes and pleasant manners, made with the coltish country folk, and above all, with that filthy, heavy, bleared scarecrow of a pirate of ours, sitting, far gone in rum, with his arms on the table. Suddenly he--the captain, that is--began to pipe up his eternal song: "Fifteen men on the dead man's chest-- Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum! Drink and the devil had done for the rest-- Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!""

"He was wild when he was young; a long while ago to be sure; but in the law of God, there is no statute of limitations. Ay, it must be that; the ghost of some old sin, the cancer of some concealed disgrace: punishment coming, PEDE CLAUDO, years after memory has forgotten and self-love condoned the fault."

"He who indulges habitually in the intoxicating pleasures of imagination, for the very reason that he reaps a greater pleasure than others, must resign himself to a keener pain, a more intolerable and utter prostration."

"He who sows hurry reaps indigestion."

"Hence it came about that I concealed my pleasures; and that when I reached years of reflection, and began to look round me, and take stock of my progress and position in the world, I stood already committed to a profound duplicity of life."

"Here he lies where he longed to be; home is the sailor, home from sea, and the hunter home from the hill."

"Here it is about gentlemen of fortune. They lives rough, and they risk swinging, but they eat and drink like fighting-cocks, and when a cruise is done, why, it's hundreds of pounds instead of hundreds of farthings in their pockets."

"Here lies one who meant well, tried a little, failed much. Surely that may be his epitaph of which he need not be ashamed."

"Here then, as I lay down the pen and proceed to seal up my confession, I bring the life of that unhappy Henry Jekyll to an end."

"His affections, like ivy, were the growth of time, they implied no aptness in the object."

"His friends were those of his own blood, or those whom he had known the longest; his affections, like ivy, were the growth of time, they implied no aptness in the object."

"His past was fairly blameless; few men could read the rolls of their life with less apprehension; yet he was humbled to the dust by the many ill things he had done, and raised up again into sober and fearful gratitude by the many he had come so near to doing, yet avoided."

"His stories were what frightened people worst of all. Dreadful stories they were--about hanging, and walking the plank, and storms at sea, and the Dry Tortugas, and wild deeds and places on the Spanish Main. By his own account he must have lived his life among some of the wickedest men that God ever allowed upon the sea, and the language in which he told these stories shocked our plain country people almost as much as the crimes that he described. My father was always saying the inn would be ruined, for people would soon cease coming there to be tyrannized over and put down, and sent shivering to their beds; but I really believe his presence did us good. People were frightened at the time, but on looking back they rather liked it; it was a fine excitement in a quiet country life, and there was even a party of the younger men who pretended to admire him, calling him a "true sea-dog" and a "real old salt" and such like names, and saying there was the sort of man that made England terrible at sea."