Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

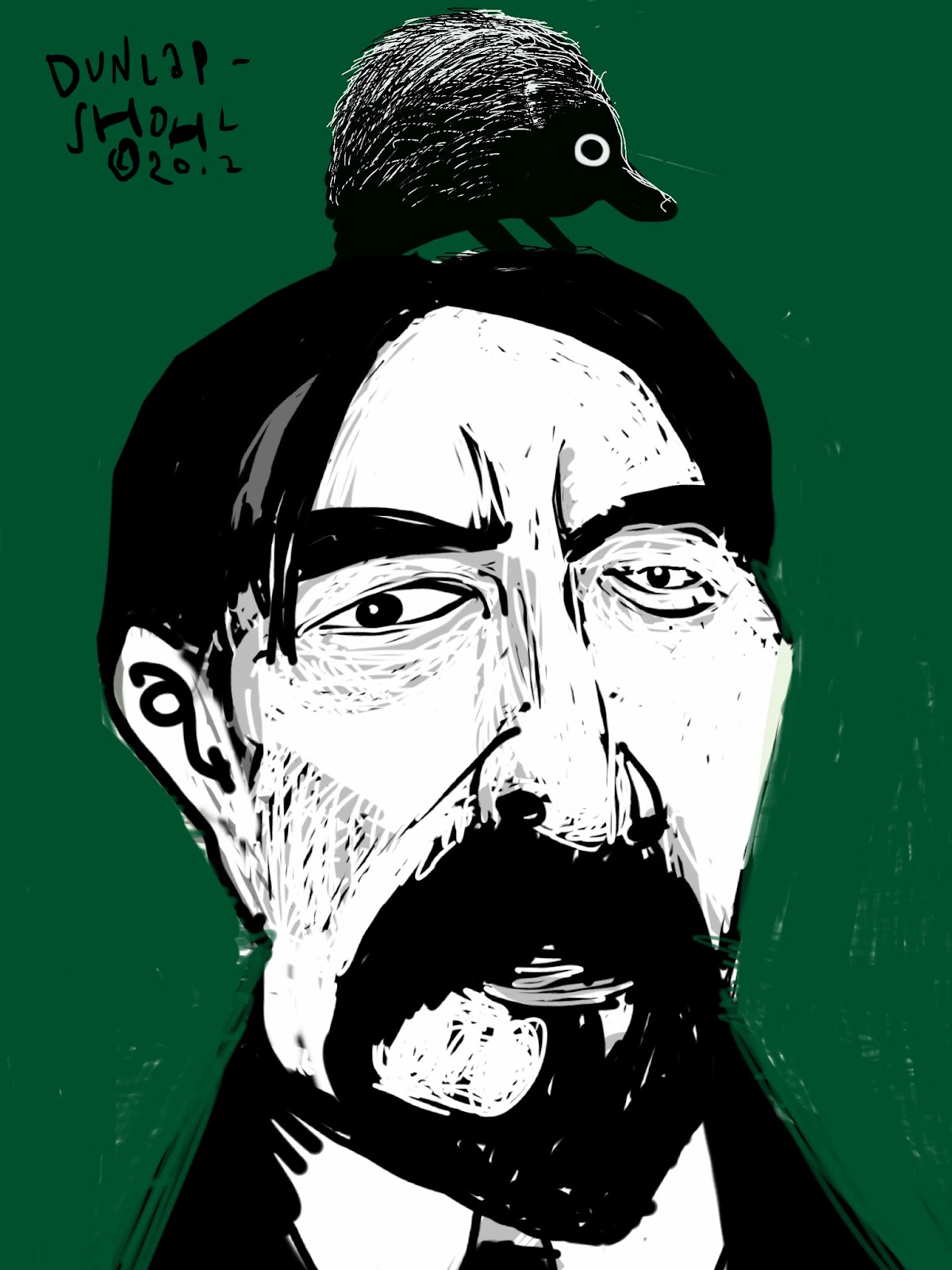

Thorstein Veblen, fully Thorstein Bunde Veblen, born Torsten Bunde Veblen

Norwegian-American Sociologist and Economist, Leader of the Institutional Economics Movement

"All these peoples that now hope to be nations have long been nationalities. A nation is an organization for collective offence and defense, in peace and war, -- essentially based on hate and fear of other nations; a nationality is a cultural group, bound together by home-bred affinities of language, tradition, use and wont, and commonly also by a supposed community race, -- essentially based on sympathies and sentiments of self-complacency within itself."

"All wastefulness is offensive to native taste. The psychological law has already been pointed out that all men?and women perhaps even in a higher degree?abhor futility, whether of effort or of expenditure... But the principle of conspicuous waste requires an obviously futile expenditure; and the resulting conspicuous expensiveness of dress is therefore intrinsically ugly."

"Already the vested interests are again tightening their hold and are busily arranging for a return to business as usual; which means working at cross-purposes as usual, waste of work and materials as usual, restriction of output as usual, unemployment as usual, labor quarrels as usual, competitive selling as usual, mendacious advertising as usual, waste of superfluities as usual by the kept classes, and privation as usual for the common man."

"Altered conditions may increase the facility of life for the group as a whole, but the redistribution will usually result in a decrease of facility or fullness of life for some members of the group."

"Among the country population its [conspicuous consumption's] place is to some extent taken by savings and home comforts known through the medium of neighborhood gossip sufficiently to serve the like general purpose of Pecuniary repute...everybody's affairs, especially everybody's pecuniary status, are known to everybody else."

"An article may be useful and wasteful both, and its utility to the consumer may be made up of use and waste in the most varying proportions."

"An auxiliary sense of taste is the sense of novelty... Hence it comes that most objects alleged to be beautiful... show considerable ingenuity of design and are calculated to puzzle the beholder?to bewilder him with irrelevant suggestions and hints of the improbable?at the same time that they give evidence of an expenditure of labor in excess of what would give them their fullest efficiency for their ostensible economic end...The result is quite as often a virtually complete suppression of all elements that would bear scrutiny as expressions of beauty, or of serviceability, and the substitution of evidences of misspent ingenuity and labor, backed by a conspicuous ineptitude; until many of the objects with which we surround ourselves in everyday life, and even many articles of everyday dress and ornament, are such as would not be tolerated except under the stress of prescriptive tradition."

"and all the while the owner of the equipment is some person who has contributed no more than his per-capita quota to this state of the industrial arts out of which his earnings arise. Indeed the chances are that the owner has contributed less than his per-capita quota, if anything, to that common fund of knowledge on the product of which he draws by virtue of his ownership, because he is likely to be fully occupied with other things, -- such things as lucrative business transactions, e.g., or the decent consumption of superfluities."

"And it is a divine right of the nation to use its discretion and offset this inordinate efficiency of its common stock of knowledge by adroitly crippling its own commerce and the commerce of its neighbors, for the benefit of those vested interests that are domiciled within the national frontiers."

"And, finally, there should be some gain of serenity in realizing how singularly consistent has been the run of economic law through the ages, and recalling, once more the reflection which John Stuart Mill arrived at some half-a-century ago, that, "Hitherto it is questionable if all the mechanical inventions yet made have lightened the day's toil of any human being.""

"Animals which merit particular attention are cats, dogs, and fast horses. The cat is less reputable than the other two just named, because she is less wasteful; she may even serve a useful end. At the same time the cat's temperament does not fit her for the honorific purpose. She lives with man on terms of equality, knows nothing of that relation of status which is the ancient basis of all distinctions of worth, honor, and repute, and she does not lend herself with facility to an invidious comparison between her owner and his neighbors. The exception to this last rule occurs in the case of such scarce and fanciful products as the Angora cat, which have some slight honorific value on the ground of expensiveness."

"Any change in men's views as to what is good and right in human life make its way but tardily at the best. Especially is this true of any change in the direction of what is called progress; that is to say, in the direction of divergence from the archaic position?from the position which may be accounted the point of departure at any step in the social evolution of the community."

"Any consumer who might, Diogenes-like, insist on the elimination of all honorific or wasteful elements from his consumption, would be unable to supply his most trivial wants in the modern market. Indeed, even if he resorted to supplying his wants directly by his own efforts... he could scarcely compass a supply of the necessaries of life for a day's consumption without instinctively and by oversight incorporating in his home-made product something of this honorific, quasi-decorative element of wasted labor."

"Any established system of law and order will remain securely stable only on condition that it he kept in line or brought into line to conform with those canons of validity that have the vogue for the time being; and the vogue is a matter of habits of thought ingrained by everyday experience. And the moral is that any established system of law and custom is due to undergo a revision of its constituent principles so soon as a new order of economic life has had time materially to affect the community's habits of thought. But all the while the changeless native proclivities of the race will assert themselves in some measure in any eventual revision of the received institutional system; and always they will stand ready eventually to break the ordered scheme of things into a paralytic mass of confusion if it cannot be bent into some passable degree of congruity with the paramount native needs of life."

"Any person with a taste for curiosities of human behavior might well pursue this question of capitalized free income into its further convolutions, and might find reasonable entertainment in so doing. The topic also has merits as a subject for economic theory. But for the present argument it may suffice to note that this free income and the business-like contrivances by which it is made secure and legitimate are of the essence of this new order of business enterprise; that the abiding incentive to such enterprise lies in this unearned income; and that the intangible assets which are framed to cover this line of "earnings," therefore, constitute the substantial core of corporate capital under the new order."

"Any valuable object in order to appeal to our sense of beauty must conform to the requirements of beauty and of expensiveness both...The marks of expensiveness come to be accepted as beautiful features of the expensive articles."

"As fast as a person makes new acquisitions, and becomes accustomed to the resulting new standard of wealth, the new standard forthwith ceases to afford appreciably greater satisfaction than the earlier standard did. The tendency in any case is constantly to make the present pecuniary standard the point of departure for a fresh increase of wealth."

"As increased industrial efficiency makes it possible to procure the means of livelihood with less labor, the energies of the industrious members of the community are bent to the compassing of a higher result in conspicuous expenditure, rather than slackened to a more comfortable pace...this want ...is indefinitely expansible, after the manner commonly imputed in economic theory to higher or spiritual wants. It is owing chiefly to... this... that J. S. Mill was able to say that "hitherto it is questionable if all the mechanical inventions yet made have lightened the day's toil of any human being.""

"As is true of the divine right of kings, so also as regards the divine right of nations, it is extremely difficult to show that it serves the common good in any material way, in any way that can be formulated or verified in terms of tangible performance."

"As regards those individuals or classes who are immediately occupied with the technique and manual operations of production... So far as concerns this portion of the population, the educative and selective action of the industrial process with which they are immediately in contact acts to adapt their habits of thought to the non-invidious purposes of the collective life. For them, therefore, it hastens the obsolescence of the distinctively predatory aptitudes and propensities carried over by heredity and tradition from the barbarian past of the race. But... are nearly all to some extent also concerned with matters of pecuniary competition (as, for instance, in the competitive fixing of wages and salaries, in the purchase of goods for consumption, etc.). Therefore the distinction here made between classes of employments is by no means a hard and fast distinction between classes of persons."

"As seen from the economic point of view, leisure, considered as an employment, is closely allied in kind with the life of exploit; and the achievements... which remain as its decorous criteria, have much in common with the trophies of exploit."

"As seen from the point of view of life under modern civilized conditions in an enlightened community of the Western culture, the primitive, ante-predatory savage... was not a great success...this primitive man has quite as many and as conspicuous economic failings as he has economic virtues?as should be plain to any one whose sense of the case is not biased by leniency born of a fellow-feeling. At his best he is "a clever, good-for-nothing fellow." The shortcomings of this presumptively primitive type of character are weakness, inefficiency, lack of initiative and ingenuity, and a yielding and indolent amiability, together with a lively but inconsequential animistic sense. Along with these traits go certain others which have some value for the collective life process, in the sense that they further the facility of life in the group. These traits are truthfulness, peaceableness, good-will, and a non-emulative, non-invidious interest in men and things."

"As seen from the point of view of the individual consumer, the question of wastefulness does not arise within the scope of economic theory proper. The use of the word "waste" as a technical term, therefore, implies no deprecation of the motives or of the ends sought by the consumer under this canon of conspicuous waste."

"As the population increases in density, and as human relations grow more complex and numerous, all the details of life undergo a process of elaboration and selection; and in this process of elaboration the use of trophies develops into a system of rank, titles, degrees and insignia, typical examples of which are heraldic devices, medals, and honorary decorations."

"As we descend the social scale, the point is presently reached where the duties of vicarious leisure and consumption devolve upon the wife alone. In the communities of the Western culture, this point is at present found among the lower middle class."

"As wealth accumulates, the leisure class develops... a more or less elaborate system of rank and grades."

"At a farther step backward in the cultural scale?among savage groups?the differentiation of employments is still less elaborate... Their culture differs... in the absence of a leisure class and the absence, in great measure, of the animus or spiritual attitude on which the institution of a leisure class rests. These communities of primitive savages in which there is no hierarchy of economic classes make up but a small and inconspicuous fraction of the human race...the class seems to include the most peaceable?perhaps all the characteristically peaceable?primitive groups of men. Indeed, the most notable trait common to members of such communities is a certain amiable inefficiency when confronted with force or fraud."

"At an earlier... stage of barbarism, the leisure class is found in a less differentiated form. Neither the class distinctions nor the distinctions between leisure-class occupations are so minute and intricate...The men of the upper classes are not only exempt, but by prescriptive custom they are debarred, from all industrial occupations. The range of employments open to them is rigidly defined. As on the higher [feudal] plane... these employments are government, warfare, religious observances, and sports. These four lines of activity govern the scheme of life of the upper classes, and for the highest rank?the kings or chieftains?these are the only kinds of activity that custom or the common sense of the community will allow."

"At home in America for the transient time being, the war administration has under pressure of necessity somewhat loosened the strangle-hold of the vested interests on the country's industry; and in so doing it has shocked the safe and sane business men into a state of indignant trepidation and has at the same time doubled the country's industrial output."

"At the other hand the guiding principles in the case at certain other points have undergone a certain refinement of interpretation with a view to greater ease and security for trade and investment; and there has, in effect, been some slight abridgement of the freedom of combination and concerted action at any point where an unguarded exercise of such freedom would hamper trade or curtail the profits of business, -- for the modern era has turned out to be an era of business enterprise, dominated by the paramount claims of trade and investment. In point of formal requirements, these restrictions imposed on concerted action "in restraint of trade" fall in equal measure on the vested interests engaged in business and on the working population engaged in industry. So that the measures taken to safeguard the natural rights of ownership apply with equal force to those who own and those who do not. "The majestic equality of the law forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges or to beg on the street corners." But it has turned out on trial that the vested interests of business are not seriously hampered by these restrictions; inasmuch as any formal restriction on any concerted action between the owners of such vested interests can always be got around by a formal coalition of ownership in the shape of a corporation. The extensive resort to corporate combination of ownership, which is so marked a feature of the nineteenth century, was not foreseen and was not taken into account in the eighteenth century, when the constituent principles of the modern point of view found their way into the common law."

"At this point, where the beautiful and the honorific meet and blend, that a discrimination between serviceability and wastefulness is most difficult in any concrete case. It frequently happens that an article which serves the honorific purpose of conspicuous waste is at the same time a beautiful object; and the same application of labor to which it owes its utility for the former purpose may, and often does, give beauty of form and color to the article."

"Barnyard fowl, hogs, cattle, sheep, goats, draught-horses. They are of the nature of productive goods, and serve a useful, often a lucrative end; therefore beauty is not readily imputed to them. The case is different with those domestic animals which ordinarily serve no industrial end; such as pigeons, parrots and other cage-birds, cats, dogs, and fast horses. These commonly are items of conspicuous consumption, and are therefore honorific in their nature and may legitimately be accounted beautiful."

"Besides servants... there is at least one other class of persons whose garb assimilates them to the class of servants and shows many of the features that go to make up the womanliness of woman's dress. This is the priestly class. Priestly vestments show, in accentuated form, all the features that have been shown to be evidence of a servile status and a vicarious life. Even more strikingly than the everyday habit of the priest, the vestments, properly so called, are ornate, grotesque, inconvenient, and, at least ostensibly, comfortless to the point of distress. The priest is at the same time expected to refrain from useful effort and, when before the public eye, to present an impassively disconsolate countenance, very much after the manner of a well-trained domestic servant."

"Born in iniquity and conceived in sin, the spirit of nationalism has never ceased to bend human institutions to the service of dissension and distress."

"Business is a pursuit of profits, and profits are to be had from profitable sales, and profitable sales can be made only if prices are maintained at a profitable level, and prices can be maintained only if the volume of marketable output is kept within reasonable limits; so that the paramount consideration in such business as has to do with the staple industries is a reasonable limitation of the output. "Reasonable" means "what the traffic will bear"; that is to say, "what will yield the largest net return.""

"But it is also to be admitted that the typical owner-employer of the earlier modern time, such as he stood in the mind's eye of the eighteenth-century doctrinaires, -- this traditional owner-employer has also come through the period of the mutation in a scarcely better state of preservation. At the period of this stabilization of principles in the eighteenth century, he could still truthfully be spoken of as a "master," a foreman of the shop, and he was then still invested with a large reminiscence of the master-craftsman, as known in the time of the craft-gilds. He stood forth in the eighteenth-century argument on the Natural Order of things as the wise and workmanlike designer and guide of his workmen's handiwork, and he was then still presumed to be living in workday contact and communion with them and to deal with them on an equitable footing of personal interest. The employer of labor in the staple industries of that time was, in his own person, commonly also the owner of the establishment in which his hired workmen were employed; and also -- again in passable accord with the facts -- he was presumed personally to come to terms with his workmen about wages and conditions of work. Employment was considered to be a relation of man to man. So soon as the machine industry began to make headway, the industrial plant increased in size, and the number of workmen employed in each establishment grew continually larger; until in the course of time the large scale of organization in industry has put any relation of man to man out of the question between employers and workmen in the leading industries."

"But it is not usual to speak of the kept classes as the uncommon classes, inasmuch they personally differ from the common run of mankind in no sensible respect. It is more usual to speak of them as "the better classes," because they are in better circumstances and are better able to do as they like. Their place in the economic scheme of the civilized world is to consume the net product of the country's industry over cost, and so prevent a glut of the market."

"But the divine right of national self-direction also covers much else of the same description, besides the privilege of setting up a tariff in restraint of trade. There are many channels of such discrimination, of diverse kinds, but always it will be found that these channels are channels of sabotage and that they serve the advantage of some group of vested interests which do business under the shelter of the national pretensions. There are foreign investments and concessions to be procured and safeguarded for the nation's business men by moral suasion backed with warlike force, and the common man pays the cost; there is discrimination to be exercised and perhaps subsidies and credits to be accorded those of the nation's business men who derive a profit from shipping, for the discomfiture of alien competitors, and the common man pays the cost; there are colonies to be procured and administered at the public expense for the private gain of certain traders, concessionaires and administrative office-holders, and the common man pays the cost. Back of it all is the nation's divine right to carry arms, to support a competitive military and naval establishment, which has ceased, under the new order, to have any other material use than to enforce or defend the businesslike right of particular vested interests to get something for nothing in some particular place and in some particular way, and the common man pays the cost and swells with pride."

"But the gravest significance of this cleavage that so runs through the population of the advanced industrial countries lies in the fact that it is a division between the vested interests and the common man. It is a division between those who control the conditions of work and the rate and volume of output and to whom the net output of industry goes as free income, on the one hand, and those others who have the work to do and to whom a livelihood is allowed by these persons in control, on the other hand. In point of numbers it is a very uneven division, of course."

"But the kept classes also comprise many persons who are entitled to a free income on other grounds than their ownership and control of industry or the market, as, e.g., landlords and other persons classed as "gentry," the clergy, the Crown ? where there is a Crown -- and its agents, civil and military. Contrasted with these classes who make up the vested interests, and who derive an income from the established order of ownership and privilege, is the common man. He is common in the respect that he is not vested with such a prescriptive right to get something for nothing. And he is called common because such is the common lot of men under the new order of business and industry; and such will continue (increasingly) to be the common lot so long as the enlightened principles of secure ownership and self-help handed down from the eighteenth century continue to rule human affairs by help of the new order of industry."

"But there are certain vested interests which find their profit in maintaining a tariff barrier as a means of keeping the price up and keeping the supply down; and the common man still faithfully believes that the profits which these vested interests derive in this way from increasing the cost of his livelihood and decreasing the net productivity of his industry will benefit him in some mysterious way."

"By and large, this eighteenth-century stabilized modern point of view has governed men's dealings within this era, and its constituent principles of right and honest living must therefore, presumptively, be held answerable for the disastrous event of it all, -- at least to the extent that they have permissively countenanced the growth of those sinister conditions which have now ripened into a state of world-wide shame and confusion."

"By further habituation to an appreciative perception of the marks of expensiveness in goods, and by habitually identifying beauty with reputability, it comes about that a beautiful article which is not expensive is accounted not beautiful. In this way... some beautiful flowers pass conventionally for offensive weeds; others that can be cultivated with relative ease are accepted and admired by the lower middle class... are rejected as vulgar by those people who are better able to pay for expensive flowers and who are educated to a higher schedule of pecuniary beauty in the florist's products"

"By use and wont, in the Liberal scheme of statecraft as well as in the scheme of freely competitive business, implicit faith has hitherto been given to the remedial effect of punitive competition and the punitive correction of excesses by law and custom. It has been a system of adjustment by punitive afterthought. All of which may once have been well enough in its time, so long as the rate and scale of the movement of things were slow enough and small enough to be effectually overtaken and set to rights by afterthought. The modern -- eighteenth-century -- point of view presumes an order of things which is amenable to remedial adjustment after the event. But the new order of industry, and that sweeping equilibrium of material forces that embodies the new order, is not amenable to afterthought. Where human life and human fortunes are exposed to the swing of the machine system, or to the onset of national ambitions that are served by the machine industry, it is safety first or none."

"By virtue of its high position as the avatar of good form, the wealthier class comes to exert a retarding influence upon social development far in excess of that which the simple numerical strength of the class would assign it."

"Canons of reputability have had a... more far-reaching... effect upon the popular sense of beauty or serviceability in consumable goods...Articles are ...felt to be serviceable somewhat in proportion as they are wasteful and ill adapted to their ostensible use...The utility of articles valued for their beauty depends closely upon the expensiveness of the articles."

"Changing institutions in their turn make for a further selection of individuals endowed with the fittest temperament, and a further adaptation of individual temperament and habits to the changing environment through the formation of new institutions."

"Chief among the honorable employments in any feudal community is warfare; and priestly service is commonly second to warfare...the rule holds with but slight exceptions that, whether warriors or priests, the upper classes are exempt from industrial employments, and this exemption is the economic expression of their superior rank."

"Closely related to the requirement that the gentleman must consume freely and of the right kind of goods, there is the requirement that he must know how to consume them in a seemly manner. His life of leisure must be conducted in due form. Hence arise good manners... High-bred manners and ways of living are items of conformity to the norm of conspicuous leisure and conspicuous consumption."

"Commonly, if not invariably, the honorific marks of hand labor are certain imperfections and irregularities in the lines of the hand-wrought article, showing where the workman has fallen short in the execution of the design. The ground of the superiority of hand-wrought goods, therefore, is a certain margin of crudeness."