Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

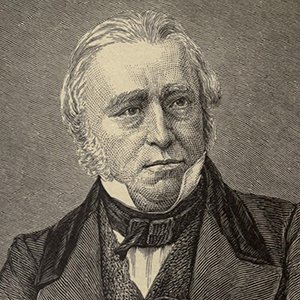

Thomas Macaulay, fully Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay

British Poet,Historian, Essayist, Biographer, Secretary of War, Paymaster-General and Whig Politician

"With all his deficiencies, Aristotle was the most enlightened and profound critic of antiquity. Dionysius was far from possessing the same exquisite subtilty, or the same vast comprehension. But he had access to a much greater number of specimens; and he had devoted himself, as it appears, more exclusively to the study of elegant literature. His peculiar judgments are of more value than his general principles. He is only the historian of literature. Aristotle is its philosopher."

"Who can believe that there is no soul behind those luminous eyes!"

"Words, and more words, and nothing but words, had been all the fruit of all the toil of all the most renowned sages of sixty generations. But the days of this sterile exuberance were numbered."

"Ye diners out from whom we guard our spoons."

"Yet this man, black with the vices which we consider as most loathsome, traitor, hypocrite, coward, assassin, was by no means destitute even of those virtues which we generally consider as indicating superior elevation of character. In civil courage, in perseverance, in presence of mind, those barbarous warriors, who were foremost in the battle or the breach, were far his inferiors. Even the dangers which he avoided with a caution almost pusillanimous never confused his perceptions, never paralyzed his inventive faculties, never wrung out one secret from his smooth tongue and his inscrutable brow. Though a dangerous enemy, and a still more dangerous accomplice, he could be a just and beneficent ruler. With so much unfairness in his policy, there was an extraordinary degree of fairness in his intellect. Indifferent to truth in the transactions of life, he was honestly devoted to truth in the researches of speculation. Wanton cruelty was not in his nature. On the contrary, where no political object was at stake, his disposition was soft and humane. The susceptibility of his nerves and the activity of his imagination inclined him to sympathize with the feelings of others, and to delight in the charities and courtesies of social life. Perpetually descending to actions which might seem to mark a mind diseased through all its faculties, he had nevertheless an exquisite sensibility both for the natural and the moral sublime, for every graceful and every lofty conception. Habits of petty intrigue and dissimulation might have rendered him incapable of great general views, but that the expanding effect of his philosophical studies counteracted the narrowing tendency. He had the keenest enjoyment of wit, eloquence, and poetry. The fine arts profited alike by the severity of his judgment and by the liberality of his patronage. The portraits of some of the remarkable Italians of those times are perfectly in harmony with this description. Ample and majestic foreheads, brows strong and dark, but not frowning, eyes of which the calm full gaze, while it expresses nothing, seems to discern everything, cheeks pale with thought and sedentary habits, lips formed with feminine delicacy but compressed with more than masculine decision, mark out men at once enterprising and timid, men equally skilled in detecting the purposes of others and in concealing their own, men who must have been formidable enemies and unsafe allies, but men, at the same time, whoso tempers were mild and equable, and who possessed an amplitude and subtlety of intellect which would have rendered them eminent either in active or in contemplative life, and fitted them either to govern or to instruct mankind."

"Your Constitution is all sail and no anchor."

"Yet, though we think that in the progress of nations towards refinement the reasoning powers are improved at the expense of the imagination, we acknowledge that to this rule there are many apparent exceptions. We are not, however, quite satisfied that they are more than apparent. Men reasoned better, for example, in the time of Elizabeth than in the time of Egbert, and they also wrote better poetry. But we must distinguish between poetry as a mental act and poetry as a species of composition. If we take it in the latter sense, its excellence depends not solely on the vigour of the imagination, but partly also on the instruments which the imagination employs. Within certain limits, therefore, poetry may be improving while the poetical faculty is decaying. The vividness of the picture presented to the reader is not necessarily proportioned to the vividness of the prototype which exists in the mind of the writer. In the other arts we see this clearly. Should a man gifted by nature with all the genius of Canova attempt to carve a statue without instruction as to the management of his chisel, or attention to the anatomy of the human body, he would produce something compared with which the Highlander at the door of a snuff-shop would deserve admiration. If an uninitiated Raphael were to attempt a painting, it would be a mere daub; indeed, the connoisseurs say that the early works of Raphael are little better. Yet who can attribute this to want of imagination? Who can doubt that the youth of that great artist was passed amidst an ideal world of beautiful and majestic forms? Or who will attribute the difference which appears between his first rude essays and his magnificent Transfiguration to a change in the constitution of his mind? In poetry, as in painting and sculpture, it is necessary that the imitator should be well acquainted with that which he undertakes to imitate, and expert in the mechanical part of his art. Genius will not furnish him with a vocabulary: it will not teach him what word most exactly corresponds to his idea and will most fully convey it to others: it will not make him a great descriptive poet, till he has looked with attention on the face of nature; or a great dramatist, till he has felt and witnessed much of the influence of the passions. Information and experience are, therefore, necessary; not for the purpose of strengthening the imagination, which is never so strong as in people incapable of reasoning,—savages, children, madmen, and dreamers; but for the purpose of enabling the artist to communicate his conceptions to others."

"Yet he [Pitt] was not a great debater. That he should not have been so when first he entered the House of Commons is not strange. Scarcely any person has ever become so without long practice and many failures. It was by slow degrees, as Burke said, that the late Mr. Fox became the most brilliant and powerful debater that ever lived. Mr. Fox himself attributed his own success to the resolution which he formed when very young, of speaking, well or ill, at least once every night. During five whole sessions, he used to say, I spoke every night but one; and I regret only that I did not speak on that night too. Indeed, with the exception of Mr. Stanley, whose knowledge of the science of parliamentary defense resembles an instinct, it would be difficult to name any eminent debater who has not made himself a master of his art at the expense of his audience. But as this art is one which even the ablest men have seldom acquired without long practice, so it is one which men of respectable abilities, with assiduous and intrepid practice, seldom fail to acquire."

"A politician must often talk and act before he has thought and read. He may be very ill informed respecting a question: all his notions about it may be vague and inaccurate; but speak he must. And if he is a man of ability, of tact, and of intrepidity, he soon find that, even under such circumstances, it is possible to speak successfully."

"In taste and imagination, in the graces of style, in the arts of persuasion, in the magnificence of public works, the ancients were at least our equals."

"History is a compound of poetry and philosophy."

"Half-knowledge is worse than ignorance."

"It is the nature of man to overrate present evil and to underrate present good; to long for what he has not, and to be dissatisfied with what he has."

"Knowledge advances by steps, and not by leaps."

"Our judgment ripens; our imagination decays. We cannot at once enjoy the flowers of the Spring of life and the fruits of its Autumn."

"Our estimate of a character always depends much on the manner in which; that character affects our own interests and passions."

"No man correctly informed as to the past will be disposed to take a morose or desponding view of the present."

"The essence of politics is compromise."

"Real security... is to be found in its benevolent morality, in its exquisite adaption to the human heart, in the facility with which its scheme accommodates itself to the capacity of every human intellect, in the consolation which it bears to every house of mourning, in the light with which it brightens the great mystery of the grave."

"The study of the properties of numbers, Plato tells us, habituate the mind to the contemplation of pure truth, and raises us above the material universe. He would have his disciples apply themselves to this study, not that they may be able to buy or sell, not that they may qualify themselves to be shopkeepers or traveling merchants, but that they may learn to withdraw their minds from the ever-shifting spectacle of this visible and tangible world, and fix them on the immutable essences of things."

"What society wants is a new motive, not a new cant."

"The smallest actual good is better than the most magnificent promise of impossibilities."

"We deplore the outrages which accompany revolutions. But the more violent the outrages, the more assured we feel that a revolution was necessary."

"Timid and interested politicians think much more about the security of their seats than about the security of their country."