Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

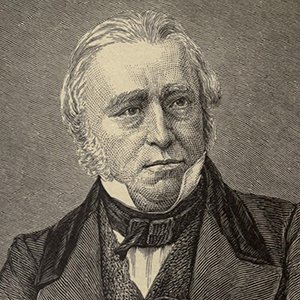

Thomas Macaulay, fully Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay

British Poet,Historian, Essayist, Biographer, Secretary of War, Paymaster-General and Whig Politician

"The least valuable of Addison’s contributions to the Spectator are, in the judgment of our age, his critical papers. Yet his critical papers are always luminous, and often ingenious. The very worst of them must be regarded as creditable to him, when the character of the school in which he had been trained is fairly considered. The best of them were much too good for his readers. In truth, he was not so far behind our generation as he was before his own. No essays in the Spectator were more censured and derided than those in which he raised his voice against the contempt with which our fine old ballads were regarded, and showed the scoffers that the same gold which, burnished and polished, gives lustre to the Æneid and the Odes of Horace, is mingled with the rude dross of Chevy Chace."

"The manner of Addison is as remote from that of Swift as from that of Voltaire. He neither laughs out like the French wit, nor, like the Irish wit, throws a double portion of severity into his countenance while laughing inwardly; but preserves a look peculiarly his own, a look of demure serenity, disturbed only by an arch sparkle of the eye, an almost imperceptible elevation of the brow, an almost imperceptible curl of the lip. His tone is never that either of a Jack Pudding or of a cynic; it is that of a gentleman, in whom the quickest sense of the ridiculous is constantly tempered by good nature and good breeding."

"The Life of Wesley [by Southey] will probably live. Defective as it is, it contains the only popular account of a most remarkable moral revolution, and of a man whose eloquence and logical acuteness might have made him eminent in literature, whose genius for government was not inferior to that of Richelieu, and who, whatever his errors [it would be difficult to name them] may have been, devoted all his powers, in defiance of obloquy and derision, to what he sincerely considered as the highest good of his species."

"The mere choice and arrangement of his words would have sufficed to make his essays classical. For never, not even by Dryden, not even by Temple, had the English language been written with such sweetness, grace, and facility. But this was the smallest part of Addison’s praise. Had he clothed his thoughts in the half-French style of Horace Walpole, or in the half-Latin style of Dr. Johnson, or in the half-German jargon of the present day, his genius would have triumphed over all faults of manner. As a moral satirist he stands unrivalled. If ever the best Tatlers and Spectators were equalled in their own kind, we should be inclined to guess that it must have been by the lost comedies of Menander."

"The maxim that governments ought to train the people in the way in which they should go, sounds well. But is there any reason for believing that a government is more likely to lead the people in the right way than the people to fall into the right way of themselves? Have there not been governments which were blind leaders of the blind? Are there not still such governments? Can it be laid down as a general rule that the movement of political and religious truth is rather downwards from the government to the people than upwards from the people to the government? These are questions which it is of importance to have clearly resolved. Mr. Southey declaims against public opinion, which is now, he tells us, usurping supreme power. Formerly, according to him, the laws governed; now public opinion governs. What are laws but expressions of the opinion of some class which has power over the rest of the community? By what was the world ever governed but by the opinion of some person or persons? By what else can it ever be governed? What are all systems, religious, political, or scientific, but opinions resting on evidence more or less satisfactory? The question is not between human opinion and some higher and more certain mode of arriving at truth, but between opinion and opinion, between the opinions of one man and another, or of one class and another, or of one generation and another. Public opinion is not infallible; but can Mr. Southey construct any institutions which shall secure to us the guidance of an infallible opinion? Can Mr. Southey select any family, any profession, any class, in short, distinguished by any plain badge from the rest of the community, whose opinion is more likely to be just than this much-abused public opinion? Would he choose the peers, for example? Or the two hundred tallest men in the country? Or the poor Knights of Windsor? Or children who are born with cauls? Or the seventh sons of seventh sons? We cannot suppose that he would recommend popular election; for that is merely an appeal to public opinion. And to say that society ought to be governed by the opinion of the wisest and best, though true, is useless. Whose opinion is to decide who are the wisest and best?"

"The measure of a man's real character is what he would do if he knew he would never be found out."

"The most elevated station that the greatest happiness principle is ever likely to attain is this, that it may be a fashionable phrase among newspaper writers and members of parliament,—that it may succeed to the dignity which has been enjoyed by the original contract, by the constitution of 1688, and other expressions of the same kind. We do not apprehend that it is a less flexible cant than those which have preceded it, or that it will less easily furnish a pretext for any design for which a pretext may be required. The original contract meant in the Convention Parliament the co-ordinate authority of the Three Estates. If there were to be a radical insurrection to-morrow, the original contract would stand just as well for annual parliaments and universal suffrage."

"The modern historians of Greece had been in the habit of writing as if the world had learned nothing new during the last sixteen hundred years. Instead of illustrating the events which they narrated by the philosophy of a more enlightened age, they judged of antiquity by itself alone. They seemed to think that notions long driven from every other corner of literature had a prescriptive right to occupy this last fastness. They considered all the ancient historians as equally authentic. They scarcely made any distinction between him who related events at which he had himself been present and him who five hundred years after composed a philosophic romance for a society which had in the interval undergone a complete change. It was all Greek, and all true! The centuries which separated Plutarch from Thucydides seemed as nothing to men who lived in an age so remote. The distance of time produced an error similar to that which is sometimes produced by distance of place. There are many good ladies who think that all the people of India live together, and who charge a friend setting out for Calcutta with kind messages to Bombay. To Rollin and Barthelemi, in the same manner, all the classics were contemporaries."

"The Novum Organum, it is true, persons who know only English must read in a translation: and this reminds me of one great advantage which such persons will derive from our Institution. They will, in our library, be able to form some acquaintance with the master-minds of remote ages and foreign countries. A large part of what is best worth knowing in ancient literature, and in the literature of France, Italy, Germany, and Spain, has been translated into our own tongue. It is scarcely possible that the translation of any book of the highest class can be equal to the original. But, though the finer touches may be lost in the copy, the great outlines will remain. An Englishman who never saw the frescoes in the Vatican may yet from engravings form some notion of the exquisite grace of Raphael and of the sublimity and energy of Michael Angelo. And so the genius of Homer is seen in the poorest version of the Iliad; the genius of Cervantes is seen in the poorest version of Don Quixote. Let it not be supposed that I wish to dissuade any person from studying either the ancient languages or the languages of modern Europe. Far from it. I prize most highly those keys of knowledge; and I think that no man who has leisure for study ought to be content until he possesses several of them. I always much admired a saying of the Emperor Charles the Fifth. When I learn a new language, he said, I feel as if I had got a new soul! But I would console those who have not time to make themselves linguists, by assuring them that by means of their own mother tongue they may obtain ready access to vast intellectual treasures, to treasures such as might have been envied by the greatest linguists of the age of Charles the Fifth, to treasures surpassing those which were possessed by Aldus, by Erasmus, and by Melancthon."

"The natural consequences followed. Left to the conduct of men who neither loved those whom they defended, nor hated those whom they opposed, who were often bound by stronger ties to the army against which they fought than to the state which they served, who lost by the termination of the conflict, and gained by its prolongation, war completely changed its character. Every man came into the field of battle impressed with the knowledge that, in a few days, he might be taking the pay of the power against which he was then employed, and fighting by the side of his enemies against his associates. The strongest interests and the strongest feelings concurred to mitigate the hostility of those who had lately been brethren in arms, and who might soon be brethren in arms once more. Their common profession was a bond of union not to be forgotten even when they were engaged in the service of contending parties. Hence it was that operations, languid and indecisive beyond any recorded in history, marches and counter-marches, pillaging expeditions and blockades, bloodless capitulations and equally bloodless combats, make up the military history of Italy during the course of nearly two centuries. Mighty armies fight from sunrise to sunset. A great victory is won. Thousands of prisoners are taken; and hardly a life is lost. A pitched battle seems to have been really less dangerous than on ordinary civil tumult. Courage was now no longer necessary even to the military character. Men grew old in camps, and acquired the highest renown by their warlike achievements, without being once required to face serious danger."

"The object of oratory alone is not truth, but persuasion."

"The opinion of Bacon on this subject was diametrically opposed to that of the ancient philosophers. He valued geometry chiefly, if not solely, on account of those uses which to Plato appeared so base. And it is remarkable that the longer Bacon lived the stronger this feeling became."

"The opinion of the great body of the reading public is very materially influenced even by the unsupported assertions of those who assume a right to criticize."

"The ordinary sophism by which misrule is defended is, when truly stated, this:—The people must continue in slavery because slavery has generated in them all the vices of slaves. Because they are ignorant, they must remain under a power which has made and which keeps them ignorant. Because they have been made ferocious by misgovernment, they must be misgoverned forever. If the system under which they live were so mild and liberal that under its operation they had become humane and enlightened, it would be safe to venture on a change. But as this system has destroyed morality, and prevented the development of the intellect,—as it has turned men, who might under different training have formed a virtuous and happy community, into savage and stupid wild beasts,—therefore it ought to last forever."

"The people are to be governed for their own good; and, that they may be governed for their own good, they must not be governed by their own ignorance. There are countries in which it would be as absurd to establish popular governments as to abolish all the restraints in a school, or to untie all the strait-waistcoats in a madhouse."

"The perfect lawgiver is a just temper between the mere man of theory, who can see nothing but general principles, and the mere man of business, who can see nothing but particular circumstances."

"The perfect historian is he in whose work the character and spirit of an age is exhibited in miniature. He relates no fact, he attributes no expression to his characters, which is not authenticated by sufficient testimony. But, by judicious selection, rejection, and arrangement, he gives to truth those attractions which have been usurped by fiction. In his narrative a due subordination is observed; some transactions are prominent; others retire. But the scale on which he represents them is increased or diminished, not according to the dignity of the persons concerned in them, but according to the degree in which they elucidate the condition of society and the nature of man. He shows us the court, the camp, and the senate. But he shows us also the nation. He considers no anecdote, no peculiarity of manner, no familiar saying, as too insignificant for his notice which is not too insignificant to illustrate the operation of laws, of religion, and of education, and to mark the progress of the human mind. Men will not merely be described, but will be made intimately known to us. The changes of manners will be indicated, not merely by a few general phrases or a few extracts from statistical documents, but by appropriate images presented in every line."

"The Pilgrim’s Progress undoubtedly is not a perfect allegory. The types are often inconsistent with each other; and sometimes the allegorical disguise is altogether thrown off. The river, for example, is emblematic of death; and we are told that every human being must pass through the river. But Faithful does not pass through it. He is martyred, not in shadow, but in reality, at Vanity Fair. Hopeful talks to Christian about Esau’s birthright and about his own convictions of sin as Bunyan might have talked with one of his own congregation. The damsels at the House Beautiful catechise Christiana’s boys as any good ladies might catechise any boys at a Sunday-school. But we do not believe that any man, whatever might be his genius, and whatever his good luck, could long continue a figurative history without falling into many inconsistencies. We are sure that inconsistencies, scarcely less gross than the worst into which Bunyan has fallen, may be found in the shortest and most elaborate allegories of the Spectator and the Rambler. The Tale of a Tub and the History of John Bull swarm with similar errors, if the name of error can be properly applied to that which is unavoidable. It is not easy to make a simile go on all-fours. But we believe that no human ingenuity could produce such a centipede as a long allegory in which the correspondence between the outward sign and the thing signified should be exactly preserved. Certainly no writer, ancient or modern, has yet achieved the adventure. The best thing, on the whole, that an allegorist can do, is to present to his readers a succession of analogies, each of which may separately be striking and happy, without looking very nicely to see whether they harmonize with each other. This Bunyan has done; and, though a minute scrutiny may detect inconsistencies in every page of his Tale, the general effect which the Tale produces on all persons, learned and unlearned, proves that he has done well."

"The plan of the Spectator must be allowed to be both original and eminently happy. Every valuable essay in the series may be read with pleasure separately; yet the five or six hundred essays form a whole, and a whole which has the interest of a novel. It must be remembered, too, that at that time no novel, giving a lively and powerful picture of the common life and manners of England, had appeared. Richardson was working as a compositor. Fielding was robbing birds’ nests. Smollett was not yet born. The narrative, therefore, which connects together the Spectator’s Essays, gave to our ancestors the first taste of an exquisite and untried pleasure. That narrative was indeed constructed with no art or labour. The events were such events as occur every day. Sir Roger comes up to town to see Eugenio, as the worthy baronet always calls Prince Eugene, goes with the Spectator on the water to Spring Gardens, walks among the tombs in the Abbey, and is frightened by the Mohawks, but conquers his apprehension so far as to go to the theatre, when the Distressed Mother is acted. The Spectator pays a visit in the summer to Coverley Hall, is charmed with the old house, the old butler, and the old chaplain, eats a jack caught by Will Wimble, rides to the assizes, and hears a point of law discussed by Tom Touchy. At last a letter from the honest butler brings to the club the news that Sir Roger is dead. Will Honeycomb marries and reforms at sixty. The club breaks up, and the Spectator resigns his functions. Such events can hardly be said to form a plot; yet they are related with such truth, such grace, such wit, such humour, such pathos, such knowledge of the human heart, such knowledge of the ways of the world, that they charm us on the hundredth perusal. We have not the least doubt that, if Addison had written a novel, on an extensive plan, it would have been superior to any that we possess. As it is, he is entitled to be considered not only as the greatest of the English essayists, but as the forerunner of the great English novelists."

"The principle of Mr. Bentham, if we understand it, is this, that mankind ought to act so as to produce their greatest happiness. The word ought, he tells us, has no meaning unless it be used with reference to some interest. But the interest of a man is synonymous with his greatest happiness:—and therefore to say that a man ought to do a thing, is to say that it is for his greatest happiness to do it. And to say that mankind ought to act so as to produce their greatest happiness, is to say that the greatest happiness is the greatest happiness,—and this is all! Does Mr. Bentham’s principle tend to make any man wish for anything for which he would not have wished, or do anything which he would not have done, if the principle had never been heard of? If not, it is an utterly useless principle. Now, every man pursues his own happiness or interest,—call it which you will. If his happiness coincides with the happiness of the species, then, whether he ever heard of the greatest happiness principle or not, he will, to the best of his knowledge and ability, attempt to produce the greatest happiness of the species. But, if what he thinks his happiness be inconsistent with the greatest happiness of mankind, will this new principle convert him to another frame of mind?"

"The principle of copyright is this: It is a tax on readers for the purpose of giving a bounty to writers. The tax is an exceedingly bad one; it is a tax on one of the most innocent and most salutary of human pleasures; and never let us forget that a tax on innocent pleasures is a premium on vicious pleasures. I admit, however, the necessity of giving a bounty to genius and learning. In order to give such a bounty I willingly submit even to this severe and burdensome tax. Nay, I am ready to increase the tax if it can be shown that by so doing I should proportionally increase the bounty."

"The progress of elegant literature and of the fine arts was proportioned to that of the public prosperity. Under the despotic successors of Augustus, all the fields of the intellect had been turned into arid wastes, still marked out by formal boundaries, still retaining the traces of old cultivation, but yielding neither flowers nor fruit. The deluge of barbarism came. It swept away all the landmarks. It obliterated all the signs of former tillage. But it fertilized while it devastated. When it receded, the wilderness was as the garden of God, rejoicing on every side, laughing, clapping its hands, pouring forth, in spontaneous abundance, everything brilliant, or fragrant, or nourishing. A new language, characterized by simple sweetness and simple energy, had attained perfection. No tongue ever furnished more gorgeous and vivid tints to poetry; nor was it long before a poet appeared, who knew how to employ them. Early in the fourteenth century came forth the Divine Comedy, beyond comparison the greatest work of imagination which had appeared since the poems of Homer. The following generation produced indeed no second Dante, but it was eminently distinguished by general intellectual activity. The study of the Latin writers had never been wholly neglected in Italy. But Petrarch introduced a more profound, liberal, and elegant scholarship, and communicated to his countrymen that enthusiasm for the literature, the history, and the antiquities of Rome, which divided his own heart with a frigid mistress and a more frigid Muse. Boccaccio turned their attention to the more sublime and graceful models of Greece."

"The Puritan hated bear-baiting not because it gave pain to the bear, but because it gave pleasure to the spectators."

"The project of mending a bad world by teaching people to give new names to old things reminds us of Walter Shandy’s scheme for compensating the loss of his son’s nose by christening him Trismegistus. What society wants is a new motive,—not a new cant. If Mr. Bentham can find out any argument yet undiscovered which may induce men to pursue the general happiness, he will indeed be a great benefactor to our species. But those whose happiness is identical with the general happiness are even now promoting the general happiness to the very best of their power and knowledge; and Mr. Bentham himself confesses that he has no means of persuading those whose happiness is not identical with the general happiness to act upon his principle. Is not this, then, darkening counsel by words without knowledge? If the only fruit of the magnificent principle is to be, that the oppressors and pilferers of the next generation are to talk of seeking the greatest happiness of the greatest number, just as the same class of men have talked in our time of seeking to uphold the Protestant constitution,—just as they talked under Anne of seeking the good of the Church, and under Cromwell of seeking the Lord,—where is the gain? Is not every great question already enveloped in a sufficiently dark cloud of unmeaning words? Is it so difficult for a man to cant some one or more of the good old English cants which his father and grandfather canted before him, that he must learn, in the schools of the Utilitarians, a new sleight of tongue to make fools clap and wise men sneer? Let our countrymen keep their eyes on the neophytes of this sect, and see whether we turn out to be mistaken in the prediction which we now hazard. It will before long be found, we prophesy, that as the corruption of a dunce is the generation of an Utilitarian, so is the corruption of an Utilitarian the generation of a jobber."

"The poetry of Milton differs from that of Dante as the hieroglyphics of Egypt differed from the picture-writing of Mexico. The images which Dante employs speak for themselves; they stand simply for what they are. Those of Milton have a signification which is often discernible only to the initiated. Their value depends less on what they directly represent than on what they remotely suggest. However strange, however grotesque, may be the appearance which Dante undertakes to describe, he never shrinks from describing it. He gives us the shape, the colour, the sound, the smell, the taste; he counts the numbers; he measures the size. His similes are the illustrations of a traveller. Unlike those of other poets, and especially of Milton, they are introduced in a plain, business-like manner; not for the sake of any beauty in the objects from which they are drawn; not for the sake of any ornament which they may impart to the poem; but simply in order to make the meaning of the writer as clear to the reader as it is to himself. The ruins of the precipice which led from the sixth to the seventh circle of hell were like those of the rock which fell into the Adige on the south of Trent. The cataract of Phlegethon was like that of Aqua Cheta at the monastery of St. Benedict. The place where the heretics were confined in burning tombs resembled the vast cemetery of Arles."

"The Puritans were men whose minds had derived a peculiar character from the daily contemplation of superior beings and eternal interests. Not content with acknowledging, in general terms, an overruling Providence, they habitually ascribed every event to the will of the Great Being, for whose power nothing was too vast, for whose inspection nothing was too minute. To know him, to serve him, to enjoy him, was with them the great end of existence. They rejected with contempt the ceremonious homage which other sects substituted for the pure worship of the soul. Instead of catching occasional glimpses of the Deity through an obscuring veil, they aspired to gaze full on his intolerable brightness, and to commune with him face to face. Hence originated their contempt for terrestrial distinctions. The difference between the greatest and the meanest of mankind seemed to vanish, when compared with the boundless interval which separated the whole race from Him on whom their own eyes were constantly fixed. They recognized no title to superiority but his favour; and, confident of that favour, they despised all the accomplishments and all the dignities of the world. If they were unacquainted with the works of philosophers and poets, they were deeply read in the oracles of God. If their names were not found in the registers of heralds, they were recorded in the Book of Life. If their steps were not accompanied by a splendid train of menials, legions of ministering angels had charge over them. Their palaces were houses not made with hands; their diadems, crowns of glory which should never fade away. On the rich and the eloquent, on nobles and priests, they looked down with contempt: for they esteemed themselves rich in a more precious treasure, and eloquent in a more sublime language, nobles by the right of an earlier creation, and priests by the imposition of a mightier hand. The very meanest of them was a being to whose fate a mysterious and terrible importance belonged, on whose slightest action the spirits of light and darkness looked with anxious interest; who had been destined, before heaven and earth were created, to enjoy a felicity which should continue when heaven and earth should have passed away. Events which short-sighted politicians ascribed to earthly causes had been ordained on his account. For his sake empires had risen, and flourished, and decayed. For his sake the Almighty had proclaimed his will by the pen of the Evangelist and the harp of the prophet. He had been wrested by no common deliverer from the grasp of no common foe. He had been ransomed by the sweat of no vulgar agony, by the blood of no earthly sacrifice. It was for him that the sun had been darkened, that the rocks had been rent, that the dead had risen, that all nature had shuddered at the sufferings of her expiring God."

"The reasoning by which Socrates, in Xenophon’s hearing, confuted the little atheist Aristodemus is exactly the reasoning of Paley’s Natural Theology. Socrates makes precisely the same use of the statues of Polycletus and the pictures of Zeuxis which Paley makes of the watch. As to the other great question, the question what becomes of man after death, we do not see that a highly-educated European, left to his unassisted reason, is more likely to be in the right than a Blackfoot Indian. Not a single one of the many sciences in which we surpass the Blackfoot Indians throws the smallest light on the state of the soul after animal life is extinct. In truth, all the philosophers, ancient and modern, who have attempted, without the help of revelation, to prove the immortality of man, from Plato down to Franklin, appear to us to have failed deplorably."

"The Romans submitted to the pretensions of a race which they despised. Their epic poet, while he claimed for them pre-eminence in the arts of government and war, acknowledged their inferiority in taste, eloquence, and science. Men of letters affected to understand the Greek language better than their own. Pomponius preferred the honour of becoming an Athenian by intellectual naturalization, to all the distinctions which were to be acquired in the political contests of Rome. His great friend composed Greek poems and memoirs. It is well known that Petrarch considered that beautiful language in which his sonnets are written as a barbarous jargon, and intrusted his fame to those wretched Latin hexameters which during the last four centuries have scarcely found four readers. Many eminent Romans appear to have felt the same contempt for their native tongue as compared with the Greek. The prejudice continued to a very late period. Julian was as partial to the Greek language as Frederic the Great to the French; and it seems that he could not express himself with elegance in the dialect of the state which he ruled."

"The question whether insults offered to a religion ought to be visited with punishment does not appear to us at all to depend on the question whether that religion be true or false. The religion may be false, but the pain which such insults give to the professors of that religion is real. It is often, as the most superficial observation may convince us, as real a pain and as acute a pain as is caused by almost any offence against the person, against property or against character. Nor is there any compensating good whatsoever to be set off against this pain. Discussion, indeed, tends to elicit truth. But insults have no such tendency. They can be employed just as easily against the purest faith as against the most monstrous superstition. It is easier to argue against falsehood than against truth. But it is as easy to pull down or defile the temples of truth as those of falsehood. It is as easy to molest with ribaldry and clamour men assembled for purposes of pious and rational worship, as men engaged in the most absurd ceremonies. Such insults when directed against erroneous opinions seldom have any other effect than to fix those opinions deeper, and to give a character of peculiar ferocity to theological dissension. Instead of eliciting truth, they only inflame fanaticism."

"The reluctant obedience of distant provinces generally costs more than it The Territory is worth. Empires which branch out widely are often more flourishing for a little timely pruning."

"The same distinction is found in the drama and in fictitious narrative. Highest among those who have exhibited human nature by means of dialogue stands Shakespeare. His variety is like the variety of nature, endless diversity, scarcely any monstrosity. The characters of which he has given us an impression as vivid as that which we receive from the characters of our own associates are to be reckoned by scores. Yet in all these scores hardly one character is to be found which deviates widely from the common standard, and which we should call very eccentric if we met it in real life. The silly notion that every man has one ruling passion, and that this clue, once known, unravels all the mysteries of his conduct, finds no countenance in the plays of Shakespeare. There man appears as he is, made up of a crowd of passions, which contend for the mastery over him, and govern him in turn. What is Hamlet’s ruling passion? Or Othello’s? Or Harry the Fifth’s? Or Wolsey’s? Or Lear’s? Or Shylock’s? Or Benedick’s? Or Macbeth’s? Or that of Cassius? Or that of Falconbridge? But we might go on forever. Take a single example, Shylock. Is he so eager for money as to be indifferent to revenge? Or so eager for revenge as to be indifferent to money? Or so bent on both together as to be indifferent to the honour of his nation and the law of Moses? All his propensities are mingled with each other, so that, in trying to apportion to each its proper part, we find the same difficulty which constantly meets us in real life. A superficial critic may say that hatred is Shylock’s ruling passion. But how many passions have amalgamated to form that hatred? It is partly the result of wounded pride: Antonio has called him dog. It is partly the result of covetousness: Antonio has hindered him of half a million; and, when Antonio is gone, there will be no limit to the gains of usury. It is partly the result of national and religious feeling: Antonio has spit on the Jewish gabardine; and the oath of revenge has been sworn by the Jewish Sabbath. We might go through all the characters which we have mentioned, and through fifty more in the same way; for it is the constant manner of Shakespeare to represent the human mind as lying, not under the absolute dominion of one despotic propensity, but under a mixed government, in which a hundred powers balance each other. Admirable as he was in all parts of his art, we most admire him for this, that while he has left us a greater number of striking portraits than all other dramatists put together, he has scarcely left us a single caricature."

"The sentimental comedy still reigned, and Goldsmith’s comedies were not sentimental."

"The severity with which the Tories, at the close of the reign of Anne, treated some of those who had directed public affairs during the War of the Grand Alliance, and the retaliatory measures of the Whigs, after the accession of the House of Hanover, cannot be justified; but they were by no means in the style of the infuriated parties whose alternate murders had disgraced our history towards the close of the reign of Charles the Second. At the fall of Walpole far greater moderation was displayed. And from that time it has been the practice, a practice not strictly according to the theory of our constitution, but still most salutary, to consider the loss of office, and the public disapprobation, as punishments sufficient for errors in the administration not imputable to personal corruption. Nothing, we believe, has contributed more than this lenity to raise the character of public men. Ambition is of itself a game sufficiently hazardous and sufficiently deep to inflame the passions, without adding property, life, and liberty to the stake. Where the play runs so desperately high as in the seventeenth century, honour is at an end. Statesmen, instead of being as they should be, at once mild and steady, are at once ferocious and inconsistent. The axe is ever before their eyes. A popular outcry sometimes unnerves them, and sometimes makes them desperate; it drives them to unworthy compliances, or to measures of vengeance as cruel as those which they have reason to expect. A Minister in our times need not fear to be firm or to be merciful. Our old policy in this respect was as absurd as that of the king in the Eastern tale who proclaimed that any physician who pleased might come to court and prescribe for his diseases, but that if the remedies failed the adventurer should lose his head. It is easy to conceive how many able men would refuse to undertake the cure on such conditions; how much the sense of extreme danger would confuse the perceptions and cloud the intellect of the practitioner, at the very crisis which most called for self-possession, and how strong his temptation would be, if he found that he had committed a blunder, to escape the consequences of it by poisoning his patient."

"The same remark will apply equally to the fine arts. The laws on which depend the progress and decline of poetry, painting, and sculpture operate with little less certainty than those which regulate the periodical returns of heat and cold, of fertility and barrenness. Those who seem to lead the public taste are, in general, merely outrunning it in the direction which it is spontaneously pursuing."

"The Sergeants made proclamation. Hastings advanced to the bar, and bent his knee. The culprit was indeed not unworthy of that great presence. He had ruled an extensive and populous country, and made laws and treaties, had sent forth armies, had set up and pulled down princes. And in his high place he had so borne himself that all had feared him, that most had loved him, and that hatred itself could deny him no title to glory, except virtue. He looked like a great man, and not like a bad man. A person small and emaciated, yet deriving dignity from a carriage which, while it indicated deference to the court, indicated also habitual self-possession and self-respect, a high and intellectual forehead, a brow pensive, but not gloomy, a mouth of inflexible decision, a face pale and worn, but serene, on which was written, as legibly as under the picture in the council-chamber at Calcutta, Mens æqua in arduis: such was the aspect with which the great proconsul presented himself to his judges."

"The spirit of the two most famous nations of antiquity was remarkably exclusive. In the time of Homer the Greeks had not begun to consider themselves as a distinct race. They still looked with something of childish wonder and awe on the riches and wisdom of Sidon and Egypt. From what causes, and by what gradations, their feelings underwent a change, it is not easy to determine. Their history, from the Trojan to the Persian war, is covered with an obscurity broken only by dim and scattered gleams of truth. But it is certain that a great alteration took place. They regarded themselves as a separate people. They had common religious rites, and common principles of public law, in which foreigners had no part. In all their political systems, monarchical, aristocratical, and democratical, there was a strong family likeness. After the retreat of Xerxes and the fall of Mardonius, national pride rendered the separation between the Greeks and the barbarians complete. The conquerors considered themselves men of a superior breed, men who, in their intercourse with neighbouring nations, were to teach, and not to learn. They looked for nothing out of themselves. They borrowed nothing. They translated nothing. We cannot call to mind a single expression of any Greek writer earlier than the age of Augustus indicating an opinion that anything worth reading could be written in any language except his own. The feelings which sprung from national glory were not altogether extinguished by national degradation. They were fondly cherished through ages of slavery and shame. The literature of Rome herself was regarded with contempt by those who had fled before her arms and who bowed beneath her fasces. Voltaire says, in one of his six thousand pamphlets, that he was the first person who told the French that England had produced eminent men besides the Duke of Marlborough. Down to a very late period the Greeks seem to have stood in need of similar information with respect to their masters. With Paulus Æmilius, Sylla, and Cæsar, they were well acquainted. But the notions which they entertained respecting Cicero and Virgil were probably not unlike those which Boileau may have formed about Shakespeare. Dionysius lived in the most splendid age of Latin poetry and eloquence. He was a critic, and, after the manner of his age, an able critic. He studied the language of Rome, associated with its learned men, and compiled its history. Yet he seems to have thought its literature valuable only for the purpose of illustrating its antiquities. His reading appears to have been confined to its public records and to a few old annalists. Once, and but once, if we remember rightly, he quotes Ennius, to solve a question of etymology. He has written much on the art of oratory: yet he has not mentioned the name of Cicero."

"The spirit which appears in the passage of Seneca to which we have referred tainted the whole body of the ancient philosophy from the time of Socrates downwards, and took possession of intellects with which that of Seneca cannot for a moment be compared. It pervades the dialogues of Plato. It may be distinctly traced in many parts of the works of Aristotle. Bacon has dropped hints from which it may be inferred that, in his opinion, the prevalence of this feeling was in a great measure to be attributed to the influence of Socrates. Our great countryman evidently did not consider the revolution which Socrates effected in philosophy as a happy event, and constantly maintained that the earlier Greek speculators, Democritus in particular, were, on the whole, superior to their more celebrated successors."

"The stronger our conviction that reason and Scripture were decidedly on the side of Protestantism, the greater is the reluctant admiration with which we regard that system of tactics against which reason and Scripture were arrayed in vain."

"The style of Bunyan is delightful to every reader, and invaluable as a study to every person who wishes to obtain a wide command over the English language. The vocabulary is the vocabulary of the common people. There is not an expression, if we except a few technical terms of theology, which would puzzle the rudest peasant. We have observed several pages which do not contain a single word of more than two syllables. Yet no writer has said more exactly what he meant to say. For magnificence, for pathos, for vehement exhortation, for subtle disquisition, for every purpose of the poet, the orator, and the divine, this homely dialect, the dialect of the workingmen, was perfectly sufficient. There is no book in our literature on which we would so readily stake the fame of the old unpolluted English language, no book which shows so well how rich that language is in its own proper wealth, and how little it has been improved by all that it has borrowed."

"The strange argument which we are considering would prove too much even for those who advance it. If no man has a right to political power, then neither Jew nor Gentile has such a right. The whole foundation of government is taken away. But if government be taken away, the property and the persons of men are insecure; and it is acknowledged that men have a right to their property and to personal security. If it be right that the property of men should be protected, and if this only can be done by means of government, then it must be right that government should exist. Now, there cannot be government unless some person or persons possess political power. Therefore it is right that some person or persons should possess political power. That is to say, some person or persons must have a right to political power."

"The style of Dante is, if not his highest, perhaps his most peculiar excellence. I know nothing with which it can be compared. The noblest models of Greek composition must yield to it. His words are the fewest and the best which it is possible to use. The first expression in which he clothes his thoughts is always so energetic and comprehensive that amplification would only injure the effect. There is probably no writer in any language who has presented so many strong pictures to the mind. Yet there is probably no writer equally concise. This perfection of style is the principal merit of the Paradiso, which, as I have already remarked, is by no means equal in other respects to the two preceding parts of the poem. The force and felicity of the diction, however, irresistibly attract the reader through the theological lectures and the sketches of ecclesiastical biography with which this division of the work too much abounds. It may seem almost absurd to quote particular specimens of an eloquence which is diffused over all his hundred cantos. I will, however, instance the third canto of the Inferno, and the sixth of the Purgatorio, as passages incomparable in their kind. The merit of the latter is, perhaps, rather oratorical than poetical; nor can I recollect anything in the great Athenian speeches which equals it in force of invective and bitterness of sarcasm. I have heard the most eloquent statesman of the age remark that, next to Demosthenes, Dante is the writer who ought to be most attentively studied by every man who desires to attain oratorical excellence."

"The style which the Utilitarians admire suits only those subjects on which it is possible to reason a priori. It grew up with the verbal sophistry which flourished during the dark ages. With that sophistry it fell before the Baconian philosophy in the day of the great deliverance of the human mind. The inductive method not only endured but required greater freedom of diction. It was impossible to reason from phenomena up to principles, to mark slight shades of difference in quality, or to estimate the comparative effect of two opposite considerations between which there was no common measure, by means of the naked and meagre jargon of the schoolmen."

"The Swiss and the Spaniards were, at that time, regarded as the best soldiers in Europe. The Swiss battalion consisted of pikemen, and bore a close resemblance to the Greek phalanx. The Spaniards, like the soldiers of Rome, were armed with the sword and the shield. The victories of Flaminius and Æmilius over the Macedonian kings seem to prove the superiority of the weapons used by the legions. The same experiment had been recently tried with the same result at the battle of Ravenna, one of those tremendous days into which human folly and wickedness compressed the whole devastation of a famine or a plague. In that memorable conflict, the infantry of Arragon, the old companions of Gonsalvo, deserted by all their allies, hewed a passage through the thickest of the imperial pikes, and effected an unbroken retreat, in the face of the gendarmerie of De Foix, and the renowned artillery of Este. Fabrizio, or rather Machiavelli, proposes to combine the two systems, to arm the foremost lines with the pike for the purpose of repulsing cavalry, and those in the rear with the sword, as being a weapon better adapted for every other purpose. Throughout the work the author expresses the highest admiration of the military science of the ancient Romans, and the greatest contempt for the maxims which had been in vogue amongst the Italian commanders of the preceding generation. He prefers infantry to cavalry, and fortified camps to fortified towns. He is inclined to substitute rapid movements and decisive engagements for the languid and dilatory operations of his countrymen. He attaches very little importance to the invention of gunpowder. Indeed, he seems to think it ought scarcely to produce any change in the mode of arming or of disposing troops. The general testimony of historians, it must be allowed, seems to prove that the ill-constructed and ill-served artillery of those times, though useful in a siege, was of little value on the field of battle."

"The truth is, that every man is, to a great extent, the creature of the age. It is to no purpose that he resists the influence which the vastness, in which he is but an atom, must exercise on him. He may try to be a man of the tenth century; but he cannot. Whether he will or no, he must be a man of the nineteenth century. He shares in the motion of the moral as well as in that of the physical world. He can no more be as intolerant as he would have been in the days of the Tudors than he can stand in the evening exactly where he stood in the morning. The globe goes round from west to east; and he must go round with it. When he says that he is where he was, he means only that he has moved at the same rate with all around him. When he says that he has gone a good way to the westward, he means only that he has not gone to the eastward quite so rapidly as his neighbours."

"The vast despotism of the Cæsars, gradually effacing all national peculiarities, and assimilating the remotest provinces of the empire to each other, augmented the evil. At the close of the third century after Christ the prospects of mankind were fearfully dreary. A system of etiquette as pompously frivolous as that of the Escurial had been established. A sovereign almost invisible; a crowd of dignitaries minutely distinguished by badges and titles; rhetoricians who said nothing but what had been said ten thousand times; schools in which nothing was taught but what had been known for ages: such was the machinery provided for the government and instruction of the most enlightened part of the human race. That great community was then in danger of experiencing a calamity far more terrible than any of the quick, inflammatory, destroying maladies to which nations are liable,—tottering, drivelling, paralytic longevity, the immortality of the Struldbrugs, a Chinese civilization. It would be easy to indicate many points of resemblance between the subjects of Diocletian and the people of that Celestial Empire where during many centuries nothing has been learned or unlearned; where government, where education, where the whole system of life, is a ceremony; where knowledge forgets to increase and multiply, and, like the talent buried in the earth, or the pound wrapped up in the napkin, experiences neither waste nor augmentation."

"The true distinction is perfectly obvious. To punish a man because we infer from the nature of some doctrine which he holds, or from the conduct of other persons who hold the same doctrines with him, that he will commit a crime, is persecution, and is, in every case, foolish and wicked."

"The voice of great events is proclaiming to us, Reform, that you may preserve"

"The vulgar notion about Bacon we take to be this: that he invented a new method of arriving at truth, which method is called Induction, and that he detected some fallacy in the syllogistic reasoning which had been in vogue before his time. This notion is about as well founded as that of the people who, in the middle ages, imagined that Virgil was a great conjurer. Many who are too well informed to talk such extravagant nonsense entertain what we think incorrect notions as to what Bacon really effected in this matter."

"The Westminster Review charges us with urging it as an objection to the greatest happiness principle that it is included in the Christian morality. This is a mere fiction of its own. We never attacked the morality of the Gospel. We blamed the Utilitarians for claiming the credit of a discovery when they had merely stolen that morality, and spoiled it in the stealing. They have taken the precept of Christ and left the motive; and they demand the praise of a most wonderful and beneficial invention when all that they have done has been to make a most useful maxim useless by separating it from its sanction. On religious principles it is true that every individual will best promote his own happiness by promoting the happiness of others. But if religious considerations be left out of the question it is not true. If we do not reason on the supposition of a future state, where is the motive? If we do reason on that supposition, where is the discovery?"

"The whole argument of the Utilitarians in favour of universal suffrage proceeds on the supposition that even the rudest and most uneducated men cannot, for any length of time, be deluded into acting against their own true interest. Yet now they tell us that in all aristocratical communities the higher and more educated class will, not occasionally, but invariably, act against its own interest. Now, the only use of proving anything, as far as we can see, is that people may believe it. To say that a man does what he believes to be against his happiness is a contradiction in terms. If, therefore, government and laws are to be constituted on the supposition on which Mr. Mill’s Essay is founded, that all individuals will, whenever they have power over others put into their hands, act in opposition to the general happiness, then government and laws must be constituted on the supposition that no individual believes, or ever will believe, his own happiness to be identical with the happiness of society. That is to say, government and laws are to be constituted on the supposition that no human being will ever be satisfied by Mr. Bentham’s proof of his greatest happiness principle,—a supposition which may be true enough, but which says little, we think, for the principle in question."