Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

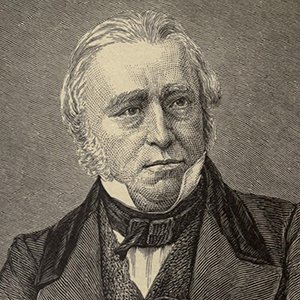

Thomas Macaulay, fully Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay

British Poet,Historian, Essayist, Biographer, Secretary of War, Paymaster-General and Whig Politician

"Oh Tiber! Father Tiber! To whom the Romans pray, a Roman's life, a Roman's arms, take thou in charge this day!"

"Oh, wherefore come ye forth in triumph from the north, / With your hands, and your feet, and your raiment all red? / And wherefore doth your rout send forth a joyous shout? / And whence be the grapes of the wine-press which ye tread?"

"Oligarchy is the weakest and the most stable of governments; and it is stable because it is weak. It has a sort of valetudinarian longevity; it lives in the balance of Sanctorius; it takes no exercise; it exposes itself to no accident; it is seized with an hypochondriac alarm at every new sensation; it trembles at every breath; it lets blood for every inflammation; and thus, without ever enjoying a day of health or pleasure, drags on its existence to a doting and debilitated old age."

"On the greatest and most useful of all human inventions, the invention of alphabetical writing, Plato did not look with much complacency. He seems to have thought that the use of letters had operated on the human mind as the use of the go-cart in learning to walk, or of corks in learning to swim, is said to operate on the human body. It was a support which, in his opinion, soon became indispensable to those who used it, which made vigorous exertion first unnecessary, and then impossible. The powers of the intellect would, he conceived, have been more fully developed without this delusive aid. Men would have been compelled to exercise the understanding and the memory, and, by deep and assiduous meditation, to make truth thoroughly their own. Now, on the contrary, much knowledge is traced on paper, but little is engraved in the soul. A man is certain that he can find information at a moment’s notice when he wants it. He therefore suffers it to fade from his mind. Such a man cannot in strictness be said to know anything. He has the show without the reality of wisdom. These opinions Plato has put into the mouth of an ancient king of Egypt. But it is evident from the context that they were his own; and so they were understood to be by Quinctilian. Indeed, they are in perfect accordance with the whole Platonic system."

"One reservation, indeed, must be made. The books and traditions of a sect may contain, mingled with propositions strictly theological, other propositions, purporting to rest on the same authority, which relate to physics. If new discoveries should throw discredit on the physical propositions, the theological propositions, unless they can be separated from the physical propositions, will share in that discredit. In this way, undoubtedly, the progress of science may indirectly serve the cause of religious truth. The Hindoo mythology, for example, is bound up with a most absurd geography. Every young Brahmin, therefore, who learns geography in our colleges learns to smile at the Hindoo mythology. If Catholicism has not suffered to an equal degree from the Papal decision that the sun goes round the earth, this is because all intelligent Catholics now hold, with Pascal, that in deciding the point at all the Church exceeded her powers, and was, therefore, justly left destitute of that supernatural assistance which in the exercise of her legitimate functions the promise of her Founder authorized her to expect."

"One single expression which Mr. Sadler employs on this subject is sufficient to show how utterly incompetent he is to discuss it. On the Christian hypothesis, says he, no doubt exists as to the origin of evil. He does not, we think, understand what is meant by the origin of evil. The Christian Scriptures profess to give no solution of the mystery. They relate facts; but they leave the metaphysical question undetermined. They tell us that man fell; but why he was not so constituted as to be incapable of falling, or why the Supreme Being has not mitigated the consequences of the Fall more than they actually have been mitigated, the Scriptures did not tell us, and, it may without presumption be said, could not tell us, unless we had been creatures different from what we are. There is something, either in the nature of our faculties or in the nature of the machinery employed by us for the purpose of reasoning, which condemns us on this and similar subjects to hopeless ignorance. Man can understand these high matters only by ceasing to be man, just as a fly can understand a lemma of Newton only by ceasing to be a fly. To make it an objection to the Christian system that it gives us no solution of these difficulties is to make it an objection to the Christian system that it is a system formed for human beings. Of the puzzles of the Academy there is not one which does not apply as strongly to Deism as to Christianity, and to Atheism as to Deism. There are difficulties in everything. Yet we are sure that something must be true."

"On the physical condition of the great body of the people government acts not as a specific, but as an alternative. Its operation is powerful, indeed, and certain, but gradual and indirect. The business of government is not directly to make the people rich, but to protect them in making themselves rich; and a government which attempts more than this is precisely the government which is likely to perform less. Governments do not and cannot support the people. We have no miraculous powers: we have not the rod of the Hebrew lawgiver: we cannot rain down bread on the multitude from Heaven: we cannot smite the rod and give them to drink. We can give them only freedom to employ their industry to the best advantage, and security in the enjoyment of what their industry has acquired. These advantages it is our duty to give them at the smallest possible cost. The diligence and forethought of individuals will thus have fair play; and it is only by the diligence and forethought of individuals that the community can become prosperous."

"On the morning of the 13th of August, in the year 1704, two great captains, equal in authority, united by close private and public ties, but of different creeds, prepared for a battle, on the event of which were staked the liberties of Europe. Marlborough had passed a part of the night in prayer, and before daybreak received the sacrament according to the rites of the Church of England. He then hastened to join Eugene, who had probably just confessed himself to a Popish priest. The generals consulted together, formed their plan in concert, and repaired each to his own post. Marlborough gave orders for public prayers. The English chaplains read the service at the head of the English regiments. The Calvinistic chaplains of the Dutch army, with heads on which hand of Bishop had never been laid, poured forth their supplications in front of their countrymen. In the mean time the Danes might listen to their Lutheran ministers; and Capuchins might encourage the Austrian squadrons, and pray to the Virgin for a blessing on the arms of the Holy Roman Empire. The battle commences, and these men of various religions all act like members of one body. The Catholic and the Protestant general exert themselves to assist and to surpass each other. Before sunset the Empire is saved. France has lost in a day the fruits of eighty years of intrigue and of victory. And the allies, after conquering together, return thanks to God separately, each after his own form of worship. Now, is this practical atheism? Would any man in his senses say, that, because the allied army had unity of action and a common interest, and because a heavy responsibility lay on its chief, it was therefore imperatively necessary that the army should, as an army, have one established religion, that Eugene should be deprived of his command for being a Catholic, that all the Dutch and Austrian colonels should be broken for not subscribing the Thirty-nine Articles? Certainly not. The most ignorant grenadier on the field of battle would have seen the absurdity of such a proposition. I know, he would have said, that the Prince of Savoy goes to mass, and that our Corporal John cannot abide it; but what has the mass to do with the taking of the village of Blenheim? The prince wants to beat the French, and so does Corporal John. If we stand by each other we shall most likely beat them. If we send all the Papists and Dutch away, Tallard will have every man of us. Mr. Gladstone himself, we imagine, would admit that our honest grenadier would have the best of the argument; and if so, what follows? Even this: that all Mr. Gladstone’s general principles about power, and responsibility, and personality, and conjoint action, must be given up; and that, if his theory is to stand at all, it must stand on some other foundation."

"Oratory is to be estimated on principles different from those which are applied to other productions. Truth is the object of philosophy and history. Truth is the object even of those works which are peculiarly called works of fiction, but which, in fact, bear the same relation to history which algebra bears to arithmetic. The merit of poetry, in its wildest forms, still consists in its truth,—truth conveyed to the understanding, not directly by the words, but circuitously by means of imaginative associations, which serve as its conductors. The object of oratory alone is not truth, but persuasion. The admiration of the multitude does not make Moore a greater poet than Coleridge, or Beattie a greater philosopher than Berkeley. But the criterion of eloquence is different. A speaker who exhausts the whole philosophy of a question, who displays every grace of style, yet produces no effect on his audience, may be a great essayist, a great statesman, a great master of composition; but he is not an orator. If he miss the mark, it makes no difference whether he have taken aim too high or too low."

"Other causes might be mentioned. But it is chiefly to the great reformation of religion that we owe the great reformation of philosophy. The alliance between the Schools and the Vatican had for ages been so close that those who threw off the dominion of the Vatican could not continue to recognize the authority of the Schools. Most of the chiefs of the schism treated the Peripatetic philosophy with contempt, and spoke of Aristotle as if Aristotle had been answerable for all the dogmas of Thomas Aquinas. Nullo apud Lutheranos philosophiam esse in pretio, was a reproach which the defenders of the Church of Rome loudly repeated, and which many of the Protestant leaders considered as a compliment. Scarcely any text was more frequently cited by the reformers than that in which St. Paul cautions the Colossians not to let any man spoil them by philosophy. Luther, almost at the outset of his career, went so far as to declare that no man could be at once a proficient in the school of Aristotle and in that of Christ. Zwingle, Bucer, Peter Martyr, Calvin, held similar language. In some of the Scotch universities the Aristotelian system was discarded for that of Ramus. Thus, before the birth of Bacon, the empire of the scholastic philosophy had been shaken to its foundations. There was in the intellectual world an anarchy resembling that which in the political world often follows the overthrow of an old and deeply-rooted government. Antiquity, prescription, the sound of great names, had ceased to awe mankind. The dynasty which had reigned for ages was at an end; and the vacant throne was left to be struggled for by pretenders."

"Only imagine a man acting for one single day on the supposition that all his neighbours believe all that they profess and act up to all that they believe. Imagine a man acting on the supposition that he may safely offer the deadliest injuries and insults to everybody who says that revenge is sinful; or that he may safely intrust all his property without security to any person who says that it is wrong to steal. Such a character would be too absurd for the wildest farce."

"Othello is perhaps the greatest work in the world! From what does it derive its power? From the clouds? From the ocean? From the mountains? Or from love strong as death, and jealousy cruel as the grave? What is it that we go forth to see in Hamlet? Is it a reed shaken with the wind? A small celandine? A bed of daffodils? Or is it to contemplate a mighty and wayward mind laid bare before us to the inmost recesses? It may perhaps be doubted whether the lakes and the hills are better fitted for the education of a poet than the dusty streets of a huge capital. Indeed, who is not tired to death with pure description of scenery? Is it not the fact that external objects never strongly excite our feelings but when they are contemplated with reference to man, as illustrating his destiny or as influencing his character? The most beautiful object in the world, it will be allowed, is a beautiful woman. But who that can analyze his feelings is not sensible that she owes her fascination less to grace of outline and delicacy of colour than to a thousand associations which, often unperceived by ourselves, connect those qualities with the source of our existence, with the nourishment of our infancy, with the passions of our youth, with the hopes of our age,—with elegance, with vivacity, with tenderness, with the strongest natural instincts, with the dearest of social lies?"

"Our constitution had begun to exist in times when statesmen were not much accustomed to frame exact definitions."

"Out of his surname they have coined an epithet for a knave, and out of his Christian name a synonym for the Devil."

"Parliamentary government is government by speaking. In such a government the power of speaking is the most highly prized of all the qualities which a politician can possess; and that power may exist in the highest degree without judgment, without fortitude, without skill in reading the characters of men or the signs of the times, without any knowledge of the principles of legislation or of political economy, and without any skill in diplomacy or in the administration of war. Nay, it may well happen that those very intellectual qualities which give a peculiar charm to the speeches of a public man may be incompatible with the qualities which would fit him to meet a pressing emergency with promptitude and firmness. It was thus with Charles Townshend. It was thus with Windham. It was a privilege to listen to those accomplished and ingenious orators. But in a perilous crisis they would have been far inferior in all the qualities of rulers to such a man as Oliver Cromwell, who talked nonsense, or to William the Silent, who did not talk at all. When parliamentary government is established, a Charles Townshend or a Windham will almost always exercise much greater influence than such men as the great protector of England or as the founder of the Batavian commonwealth. In such a government parliamentary talent, though quite distinct from the talents of a good executive or judicial officer, will be a chief qualification for executive and judicial office. From the Book of Dignities a curious list might be made out of Chancellors ignorant of the principles of equity and First Lords of the Admiralty ignorant of the principles of navigation, of Colonial ministers who could not repeat the names of the Colonies, of Lords of the Treasury who did not know the difference between funded and unfunded debt, and of Secretaries of the India Board who did not know whether the Mahrattas were Mahometans or Hindoos."

"Our notions about government are not, however, altogether unsettled. We have an opinion about parliamentary reform, though we have not arrived at that opinion by the royal road which Mr. Mill has opened for the explorers of political science. As we are taking leave, probably for the last time, of this controversy, we will state very concisely what our doctrines are. On some future occasion we may, perhaps, explain and defend them at length. Our fervent wish, and, we will add, our sanguine hope, is that we may see such a reform of the House of Commons as may render its votes the express image of the opinion of the middle orders of Britain. A pecuniary qualification we think absolutely necessary; and in settling its amount our object would be to draw the line in such a manner that every decent farmer and shopkeeper might possess the elective franchise. We should wish to see an end put to all the advantages which particular forms of property possess over other forms, and particular portions of property over other equal portions. And this would content us. Such a reform would, according to Mr. Mill, establish an aristocracy of wealth, and leave the community without protection and exposed to all the evils of unbridled power. Most willingly would we stake the whole controversy between us on the success of the experiment which we propose."

"Our rulers will best promote the improvement of the nation by strictly confining themselves to their own legitimate duties, by leaving capital to find its most lucrative course, commodities their fair price, industry and intelligence their natural reward, idleness and folly their natural punishment, by maintaining peace, by defending property, by diminishing the price of law, and by observing strict economy in every department of the state. Let the Government do this: the People will assuredly do the rest."

"People crushed by law have no hopes but from power. If laws are their enemies, they will be enemies to laws."

"Perhaps it may be laid down as a general rule that a legislative assembly, not constituted on democratic principles, cannot be popular long after it ceases to be weak. Its zeal for what the people, rightly or wrongly, conceive to be their interest, its sympathy with their mutable and violent passions, are merely the effects of the particular circumstances in which it is placed. As long as it depends for existence on the public favour, it will employ all the means in its power to conciliate that favour. While this is the case, defects in its constitution are of little consequence. But, as the close union of such a body with the nation is the effect of an identity of interest not essential but accidental, it is in some measure dissolved from the time at which the danger which produced it ceases to exist."

"Perhaps the gods and demons of Æschylus may best bear a comparison with the angels and devils of Milton. The style of the Athenian had, as we have remarked, something of the Oriental character; and the same peculiarity may be traced in his mythology. It has nothing of the amenity and elegance which we generally find in the superstitions of Greece. All is rugged, barbaric, and colossal. The legends of Æschylus seem to harmonize less with the fragrant groves and graceful porticoes in which his countrymen paid their vows to the God of Light and Goddess of Desire, than with those huge and grotesque labyrinths of eternal granite in which Egypt enshrined her mystic Osiris, or in which Hindostan still bows down to her seven-headed idols. His favourite gods are those of the elder generation, the sons of heaven and earth, compared with whom Jupiter himself was a stripling and an upstart, the gigantic Titans and the inexorable Furies. Foremost among his creations of this class stands Prometheus, half fiend, half redeemer, the friend of man, the sullen and implacable enemy of heaven. Prometheus bears undoubtedly a considerable resemblance to the Satan of Milton. In both we find the same impatience of control, the same ferocity, the same unconquerable pride. In both characters also are mingled, though in very different proportions, some kind and generous feelings. Prometheus, however, is hardly superhuman enough. He talks too much of his chains and his uneasy posture: he is rather too much depressed and agitated. His resolution seems to depend on the knowledge which he possesses that he holds the fate of his torturer in his hands, and that the hour of his release will surely come."

"Perhaps no person can be a poet, or can even enjoy poetry, without a certain unsoundness of mind, if anything which gives so much pleasure can be called unsoundness. By poetry we mean not all writing in verse, nor even all good writing in verse. Our definition excludes many metrical compositions which, on other grounds, deserve the highest praise. By poetry we mean the art of employing words in such a manner as to produce an illusion on the imagination, the art of doing by means of words what the painter does by means of colours. Thus the greatest of poets has described it, in lines universally admired for the vigour and felicity of their diction, and still more valuable on account of the just notion which they convey of the art in which he excelled:"

"Persecution produced its natural effect on them. It found them a sect; it made them a faction."

"Perhaps the best way of describing Addison’s peculiar pleasantry is to compare it with the pleasantry of some other great satirists. The three most eminent masters of the art of ridicule, during the eighteenth century, were, we conceive, Addison, Swift, and Voltaire. Which of the three had the greatest power of moving laughter may be questioned. But each of them, within his own domain, was supreme."

"Place Ignatius Loyola at Oxford. He is certain to become the head of a formidable secession. Place John Wesley at Rome. He is certain to be the first General of a new society devoted to the interests and honour of the Church. Place St. Theresa in London. Her restless enthusiasm ferments into madness, not untinctured with craft. She becomes the prophetess, the mother of the faithful, holds disputations with the devil, issues sealed pardons to her adorers, and lies in of the Shiloh. Place Joanna Southcote at Rome. She founds an order of barefooted Carmelites, every one of whom is ready to suffer martyrdom for the Church: a solemn service is consecrated to her memory; and her statue, placed over the holy water, strikes the eye of every stranger who enters St. Peter’s."

"Politeness has been well defined as benevolence in small things."

"Plautus was, unquestionably, one of the best Latin writers; but the Casina is by no means one of his best plays; nor is it one which offers great facilities to an imitator. The story is as alien from modern habits of life as the manner in which it is developed from the modern fashion of composition. The lover remains in the country and the heroine in her chamber during the whole action, leaving their fate to be decided by a foolish father, a cunning mother, and two knavish servants. Machiavelli has executed his task with judgment and taste. He has accommodated the plot to a different state of society, and has very dexterously connected it with the history of his own times. The relation of the trick put upon the doting old lover is exquisitely humorous. It is far superior to the corresponding passage in the Latin comedy, and scarcely yields to the account which Falstaff gives of his ducking."

"Poetry produces an illusion on the eye of the mind, as a magic lantern produces an illusion on the eye of the body. And, as the magic lantern acts best in a dark room, poetry effects its purpose most completely in a dark age. As the light of knowledge breaks in upon its exhibitions, as the outlines of certainty become more and more definite, and the shades of probability more and more distinct, the lines and lineaments of the phantoms which the poet calls up grow fainter and fainter. We cannot unite the incompatible advantages of reality and deception, the clear discernment of truth and the exquisite enjoyment of fiction."

"Portocarrero was one of a race of men of whom we, happily for us, have seen but very little, but whose influence has been the curse of Roman Catholic countries. He was, like Sixtus the Fourth and Alexander the Sixth, a politician made out of an impious priest. Such politicians are generally worse than the worst of the laity, more merciless than any ruffian that can be found in camps, more dishonest than any pettifogger who haunts the tribunals. The sanctity of their profession has an unsanctifying influence on them. The lessons of the nursery, the habits of boyhood and of early youth, leave in the minds of the great majority of avowed infidels some traces of religion, which, in seasons of mourning and of sickness, become plainly discernible. But it is scarcely possible that any such trace should remain in the mind of the hypocrite who, during many years, is constantly going through what he considers as the mummery of preaching, saying mass, baptizing, shriving. When an ecclesiastic of this sort mixes in the contests of men of the world, he is indeed much to be dreaded as an enemy, but still more to be dreaded as an ally. From the pulpit where he daily employs his eloquence to embellish what he regards as fables, from the altar whence he daily looks down with secret scorn on the prostrate dupes who believe that he can turn a drop of wine into blood, from the confessional where he daily studies with cold and scientific attention the morbid anatomy of guilty consciences, he brings to courts some talents which may move the envy of the more cunning and unscrupulous of lay courtiers: a rare skill in reading characters and in managing tempers, a rare art of dissimulation, a rare dexterity in insinuating what it is not safe to affirm or to propose in explicit terms."

"Press where ye see my white plume shine, amidst the ranks of war, and be your oriflamme today the helmet of Navarre."

"Propriety of thought and propriety of diction are commonly found together. Obscurity and affectation are the two greatest faults of style. Obscurity of expression generally springs from confusion of ideas; and the same wish to dazzle at any cost which produces affectation in the manner of a writer is likely to produce sophistry in his reasonings. The judicious and candid mind of Machiavelli shows itself in his luminous, manly, and polished language. The style of Montesquieu, on the other hand, indicates in every page a lively and ingenious but an unsound mind. Every trick of expression, from the mysterious conciseness of an oracle to the flippancy of a Parisian coxcomb, is employed to disguise the fallacy of some positions and the triteness of others. Absurdities are brightened into epigrams; truisms are darkened into enigmas. It is with difficulty that the strongest eye can sustain the glare with which some parts are illuminated, or penetrate the shade in which others are concealed."

"Pure democracy, and pure democracy alone, satisfies the former condition of this great problem. That the governors may be solicitous only for the interests of the governed, it is necessary that the interests of the governors and the governed should be the same. This cannot often be the case where power is intrusted to one or to a few. The privileged part of the community will doubtless derive a certain degree of advantage from the general prosperity of the state; but they will derive a greater from oppression and exaction. The king will desire an useless war for his glory, or a parc-aux-cerfs for his pleasure. The nobles will demand monopolies and lettres-de-cachet. In proportion as the number of governors is increased, the evil is diminished. There are fewer to contribute, and more to receive. The dividend which each can obtain of the public plunder becomes less and less tempting. But the interests of the subjects and the rulers never absolutely coincide till the subjects themselves become the rulers, that is, till the government be either immediately or mediately democratical."

"Reform, that we may preserve."

"Quintilian applied to general literature the same principles by which he had been accustomed to judge of the declamations of his pupils. He looks for nothing but rhetoric, and rhetoric not of the highest order. He speaks coldly of the incomparable works of Æschylus. He admires, beyond expression, those inexhaustible mines of commonplaces, the plays of Euripides. He bestows a few vague words on the poetical character of Homer. He then proceeds to consider him merely as an orator. An orator Homer doubtless was, and a great orator. But surely nothing is more remarkable in his admirable works than the art with which his oratorical powers are made subservient to the purposes of poetry. Nor can I think Quintilian a great critic in his own province. Just as are many of his remarks, beautiful as are many of his illustrations, we can perpetually detect in his thoughts that flavour which the soil of despotism generally communicates to all the fruits of genius. Eloquence was, in his time, little more than a condiment which served to stimulate in a despot the jaded appetite for panegyric, an amusement for the travelled nobles and the blue-stocking matrons of Rome. It is, therefore, with him rather a sport than a war; it is a contest of foils, not of swords. He appears to think more of the grace of the attitude than of the direction and vigour of the thrust. It must be acknowledged, in justice to Quintilian, that this is an error to which Cicero has too often given the sanction both of his precept and of his example."

"QueenMary had a way of interrupting tattle about elopements, duels, and play debts, by asking the tattlers, very quietly yet significantly, whether they had ever read her favourite sermon, Doctor Tillotson’s, on Evil Speaking."

"Scotland by no means escaped the fate ordained for every country which is connected, but not incorporated, with another country of greater resources. Though in name an independent kingdom, she was, during more than a century, really treated in many respects as a subject province."

"Seeing these things, seeing that, by the confession of the most obstinate enemies of innovation, our race has hitherto been almost constantly advancing in knowledge, and not seeing any reason to believe that, precisely at the point of time at which we came into the world, a change took place in the faculties of the human mind or in the mode of discovering truth, we are reformers: we are on the side of progress. From the great advances which European society has made, during the last four centuries, in every species of knowledge, we infer, not that there is no room for improvement, but that, in every science which deserves the name, immense improvements may be confidently expected."

"Rulers must not be suffered thus to absolve themselves of their solemn responsibility. It does not lie in their mouths to say that a sect is not patriotic. It is their business to make it patriotic. History and reason clearly indicate the means. The English Jews are, as far as we can see, precisely what our government has made them. They are precisely what any sect, what any class of men, treated as they have been treated, would have been. If all the red-haired people of Europe had, during centuries, been outraged and oppressed, banished from this place, imprisoned in that, deprived of their money, deprived of their teeth, convicted of the most improbable crimes on the feeblest evidence, dragged at horses’ tails, hanged, tortured, burned alive; if, when manners became milder, they had still been subject to debasing restrictions and exposed to vulgar insults, locked up in particular streets in some countries, pelted and ducked by the rabble in others, excluded everywhere from magistracies and honours,—what would be the patriotism of gentlemen with red hair? And if, under such circumstances, a proposition were made for admitting red-haired men to office, how striking a speech might an eloquent admirer of our old institutions deliver against so revolutionary a measure! These men, he might say, scarcely consider themselves as Englishmen. They think a red-haired Frenchman or a red-haired German more closely connected with them than a man with brown hair born in their own parish. If a foreign sovereign patronizes red hair, they love him better than their own native king."

"She [the Catholic Church] thoroughly understands what no other Church has ever understood, how to deal with enthusiasts."

"Shakespeare has had neither equal nor second. But among the writers who, in the point which we have noticed, have approached nearest to the manner of the great master, we have no hesitation in placing Jane Austen, a woman of whom England is justly proud. She has given us a multitude of characters, all, in a certain sense, commonplace, all such as we meet every day. Yet they are all as perfectly discriminated from each other as if they were the most eccentric of human beings. There are, for example, four clergymen, none of whom we should be surprised to find in any parsonage of the kingdom, Mr. Edward Ferrars, Mr. Henry Tilney, Mr. Edmund Bertram, and Mr. Elton. They are all specimens of the upper part of the middle class. They have all been liberally educated. They all lie under the restraints of the same sacred profession. They are all young. They are all in love. Not one of them has any hobby-horse, to use the phrase of Sterne. Not one has a ruling passion, such as we read of in Pope. Who would not have expected them to be insipid likenesses of each other? No such thing. Harpagon is not more unlike to Jourdain, Joseph Surface is not more unlike to Sir Lucius O’Trigger, then every one of Miss Austen’s young divines to all his reverend brethren. And almost all this is done by touches so delicate that they elude analysis, that they defy the powers of description, and that we know them to exist only by the general effect to which they have contributed."

"She [the Roman Catholic Church] may still exist in undiminished vigour when some traveller from New Zealand shall, in the midst of a vast solitude, take his stand on a broken arch of London Bridge to sketch the ruins of St. Paul’s."

"She thoroughly understands what no other Church has ever understood, how to deal with enthusiasts."

"Sir Francis Macnaghten tells us that it is a delusion to fancy that there is any known and fixed law under which the Hindoo people live; that texts may be produced on any side of any question; that expositors equal in authority perpetually contradict each other; that the obsolete law is perpetually confounded with the law actually in force; and that the first lesson to be impressed on a functionary who has to administer law is that it is in vain to think of extracting certainty from the books of the jurist. The consequence is that in practice the decisions of the tribunal are altogether arbitrary. What is administered is not law, but a kind of rude and capricious equity. I asked an able and excellent judge lately returned from India how one of our Zillah Courts would decide several legal questions of great importance, questions not involving considerations of religion or of caste, mere questions of commercial law. He told me that it was a mere lottery. He knew how he should himself decide them. But he knew nothing more. I asked a most distinguished civil servant of the Company, with reference to the clause of this Bill on the subject of slavery, whether, at present, if a dancing-girl ran away from her master the judge would force her to go back. Some judges, he said, send a girl back. Others set her at liberty. The whole is a mere matter of chance. Everything depends on the temper of the individual judge."

"Sir, in supporting the motion of my honourable friend, I am, I firmly believe, supporting the honour and the interests of the Christian religion. I should think that I insulted that religion if I said that it cannot stand unaided by intolerant laws. Without such laws it was established, and without such laws it may be maintained. It triumphed over the superstitions of the most refined and of the most savage nations, over the graceful mythology of Greece and the bloody idolatry of the Northern forests. It prevailed over the power and policy of the Roman empire. It tamed the barbarians by whom that empire was overthrown. But all these victories were gained not by the help of intolerance, but in spite of the opposition of intolerance. The whole history of Christianity proves that she has indeed little to fear from persecution as a foe, but much to fear from persecution as an ally. May she long continue to bless our country with her benignant influence, strong in her sublime philosophy, strong in her spotless morality, strong in those internal and external evidences to which the most powerful and comprehensive of human intellects have yielded assent, the last solace of those who have outlived every earthly hope, the last restraint of those who are raised above every earthly fear! But let us not, mistaking her character and her interests, fight the battle of truth with the weapons of error, and endeavour to support by oppression that religion which first taught the human race the great lesson of universal charity."

"Sir, there is no reaction; and there will be no reaction. All that has been said on this subject convinces me only that those who are now, for the second time, raising this cry, know nothing of the crisis in which they are called on to act, or of the nation which they aspire to govern. All their opinions respecting this bill are founded on one great error. They imagine that the public feeling concerning Reform is a mere whim which sprang up suddenly out of nothing and which will as suddenly vanish into nothing. They, therefore, confidently expect a reaction. They are always looking out for a reaction. Everything that they see or that they bear they construe into a sign of the approach of this reaction. They resemble the man in Horace who lies on the bank of the river expecting that it will every moment pass by and leave him a clear passage, not knowing the depth and abundance of the fountain which feeds it, not knowing that it flows, and will flow on forever."

"So, in this way of writing without thinking"

"Some men, of whom I wish to speak with great respect, are haunted, as it seems to me, with an unreasonable fear of what they call superficial knowledge. Knowledge, they say, which really deserves the name is a great blessing to mankind, the ally of virtue, the harbinger of freedom. But such knowledge must be profound. A crowd of people who have a smattering of mathematics, a smattering of astronomy, a smattering of chemistry, who have read a little poetry and a little history, is dangerous to the commonwealth. Such half-knowledge is worse than ignorance. And then the authority of Pope is vouched: Drink deep, or taste not; shallow draughts intoxicate: drink largely; and that will sober you. I must confess that the danger which alarms these gentlemen never seemed to me very serious: and my reason is this: that I never could prevail on any person who pronounced superficial knowledge a curse and profound knowledge a blessing to tell me what was his standard of profundity. The argument proceeds on the supposition that there is some line between profound and superficial knowledge similar to that which separates truth from falsehood. I know of no such line. When we talk of men of deep science, do we mean that they have got to the bottom or near the bottom of science? Do we mean that they know all that is capable of being known? Do we mean even that they know in their own especial department all that the smatterers of the next generation will know? Why, if we compare the little truth that we know with the infinite mass of truth which we do not know, we are all shallow together; and the greatest philosophers that ever lived would be the first to confess their shallowness. If we could call up the first of human beings, if we could call up Newton, and ask him whether, even in those sciences in which he had no rival, he considered himself as profoundly knowing, he would have told us that he was but a smatterer like ourselves, and that the difference between his knowledge and ours vanished when compared with the quantity of truth still undiscovered, just as the distance between a person at the foot of Ben Lomond and at the top of Ben Lomond vanishes when compared with the distance of the fixed stars."

"So true is it that nature has caprices which art cannot imitate."

"Society indeed has its great men and its little men, as the earth has its mountains and its valleys. But the inequalities of intellect, like the inequalities of the surface of our globe, bear so small a proportion to the mass that in calculating its great revolutions they may safely be neglected. The sun illuminates the hills whilst it is still below the horizon, and truth is discovered by the highest minds a little before it becomes manifest to the multitude. This is the extent of their superiority. They are the first to catch and reflect a light which, without their assistance, must in a short time be visible to those who lie far beneath them."

"Some of Johnson’s whims on literary subjects can be compared only to that strange nervous feeling which made him uneasy if he had not touched every post between the Mitre tavern and his own lodgings. His preference of Latin epitaphs to English epitaphs is an instance. An English epitaph, he said, would disgrace Smollett. He declared that he would not pollute the walls of Westminster Abbey with an English epitaph on Goldsmith. What reason there can be for celebrating a British writer in Latin, which there was not for covering the Roman arches of triumph with Greek inscriptions, or for commemorating the deeds of the heroes of Thermopylæ in Egyptian hieroglyphics, we are utterly unable to imagine."

"Some capricious and discontented artists have affected to consider portrait-painting as unworthy a man of genius. Some critics have spoken in the same contemptuous manner of history. Johnson puts the case thus: The historian tells either what is false or what is true: in the former case he is no historian; in the latter he has no opportunity for displaying his abilities: for truth is one: and all who tell the truth must tell it alike."