Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

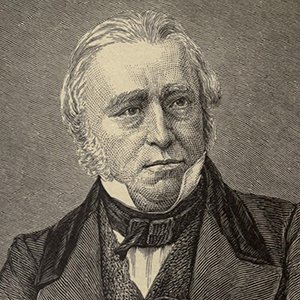

Thomas Macaulay, fully Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay

British Poet,Historian, Essayist, Biographer, Secretary of War, Paymaster-General and Whig Politician

"Hence, before the Revolution, the question of Parliamentary reform was of very little importance. The friends of liberty had no very ardent wish for reform."

"His [Goldsmith’s] fame was great, and was constantly rising. He lived in what was intellectually far the best society of the kingdom, in a society in which no talent or accomplishment was wanting, and in which the art of conversation was cultivated with splendid success. There probably were never four talkers more admirable in four different ways than Johnson, Burke, Beauclerc, and Garrick; and Goldsmith was on terms of intimacy with all the four. He aspired to share in their colloquial renown; but never was ambition more unfortunate. It may seem strange that a man who wrote with so much perspicuity, vivacity, and grace, should have been, whenever he took a part in conversation, an empty, noisy, blundering rattle. But on this point the evidence is overwhelming."

"Hence it may be concluded that the happiest state of society is that in which supreme power resides in the whole body of a well-informed people. This is an imaginary, perhaps an unattainable, state of things. Yet, in some measure, we may approximate to it; and he alone deserves the name of a great statesman whose principle it is to extend the power of the people in proportion to the extent of their knowledge, and to give them every facility for obtaining such a degree of knowledge as may render it safe to trust them with absolute power. In the meantime, it is dangerous to praise or condemn constitutions in the abstract; since, from the despotism of St. Petersburg to the democracy of Washington, there is scarcely a form of government which might not, at least in some hypothetical case, be the best possible."

"His figure, when he first appeared in Parliament, was strikingly graceful and commanding, his features high and noble, his eye full of fire. His voice, even when he sank it to a whisper, was heard to the remotest benches; and when he strained it to its full extent, the sound rose like the swell of the organ of a great cathedral, shook the house with its peal, and was heard through lobbies and down staircases, to the Court of Requests and the precincts of Westminster Hall. He cultivated all these eminent advantages with the most assiduous care. His action is described by a very malignant observer as equal to that of Garrick. His play of countenance was wonderful: he frequently disconcerted a hostile orator by a single glance of indignation or scorn. Every tone, from the impassioned cry to the thrilling aside, was perfectly at his command. It is by no means improbable that the pains which he took to improve his great personal advantages had, in some respects, a prejudicial operation, and tended to nourish in him that passion for theatrical effect which, as we have already remarked, was one of the most conspicuous blemishes in his character."

"His imagination resembled the wings of an ostrich. It enabled him to run, though not to soar."

"His plays, his rhyming plays in particular, are admirable subjects for those who wish to study the morbid anatomy of the drama. He was utterly destitute of the power of exhibiting real human beings. Even in the far inferior talent of composing characters out of those elements into which the imperfect process of our reason can resolve them, he was very deficient. His men are not even good personifications; they are not well-assorted assemblages of qualities. Now and then, indeed, he seizes a very coarse and marked distinction, and gives us, not a likeness, but a strong caricature, in which a single peculiarity is protruded, and everything else neglected; like the Marquis of Granby at an inn-door, whom we know by nothing but his baldness; or Wilkes, who is Wilkes only in his squint. These are the best specimens of his skill. For most of his pictures seem, like Turkey carpets, to have been expressly designed not to resemble anything in the heavens above, in the earth beneath, or in the waters under the earth."

"His oratory is utterly and irretrievably lost to us, like that of Somers, of Bolingbroke, of Charles Townshend, of many others who were accustomed to rise amidst the breathless expectation of senates and to sit down amidst reiterated bursts of applause. But old men who lived to admire the eloquence of Pulteney in its meridian, and that of Pitt in its splendid dawn, still murmured that they had heard nothing like the great speeches of Lord Halifax on the Exclusion Bill. The power of Shaftesbury over large masses was unrivalled. Halifax was disqualified by his whole character, moral and intellectual, for the part of a demagogue. It was in small circles, and, above all, in the House of Lords, that his ascendency was felt."

"History has its foreground and its background, and it is principally in the management of its perspective that one artist differs from another. Some events must be represented on a large scale, others diminished; the great majority will be lost in the dimness of the horizon, and a general idea of their joint effect will be given by a few slight touches."

"History is full of the signs of this natural progress of society. We see in almost every part of the annals of mankind how the industry of individuals, struggling up against wars, taxes, famines, conflagrations, mischievous prohibitions, and more mischievous protections, creates faster than governments can squander, and repairs whatever invaders can destroy. We see the wealth of nations increasing, and all the arts of life approaching nearer and nearer to perfection, in spite of the grossest corruption and the wildest profusion on the part of rulers."

"History was, in his [Johnson’s] opinion, to use the fine expression of Lord Plunkett, an old almanack: historians could, as he conceived, claim no higher dignity than that of almanack makers; and his favourite historians were those who, like Lord Hailes, aspired to no higher dignity. He always spoke with contempt of Robertson. Hume he would not even read. He affronted one of his friends for talking to him about Catiline’s conspiracy, and declared that he never desired to hear of the Punic war again as long as he lived."

"History, is made up of the bad actions of extraordinary men and woman. All the most noted destroyers and deceivers of our species, all the founders of arbitrary governments and false religions have been extraordinary people; and nine tenths of the calamities that have befallen the human race had no other origin than the union of high intelligence with low desires."

"History, at least in its state of ideal perfection, is a compound of poetry and philosophy. It impresses general truths on the mind by a vivid representation of particular characters and incidents. But, in fact, the two hostile elements of which it consists have never been known to form a perfect amalgamation; and, at length, in our own time, they have been completely and professedly separated. Good histories, in the proper sense of the word, we have not. But we have good historical romances, and good historical essays. The imagination and the reason, if we may use a legal metaphor, have made partition of a province of literature of which they were formerly seised per my et per tout; and now they hold their respective portions in severalty, instead of holding the whole in common."

"How it chanced that a man who reasoned on his premises so ably should assume his premises so foolishly, is one of the great mysteries of human nature. The same inconsistency may be observed in the schoolmen of the middle ages. Those writers show so much acuteness and force of mind in arguing on their wretched data, that a modern reader is perpetually at a loss to comprehend how such minds came by such data. Not a flaw in the superstructure which they are rearing escapes their vigilance. Yet they are blind to the obvious unsoundness of the foundation. It is the same with some eminent lawyers. Their legal arguments are intellectual prodigies, abounding with the happiest analogies and the most refined distinctions. The principles of their arbitrary science being once admitted, the statute-book and the reports being once assumed as the foundations of reasoning, these men must be allowed to be perfect masters of logic. But if a question arises as to the postulates on which their whole system rests, if they are called upon to vindicate the fundamental maxims of that system which they have passed their lives in studying, these very men often talk the language of savages or children. Those who have listened to a man of this class in his own court, and who have witnessed the skill with which he analyzes and digests a vast mass of evidence, or reconciles a crowd of precedents which at first sight seem contradictory, scarcely know him again when, a few hours later, they hear him speaking on the other side of Westminster Hall in his capacity of legislator. They can scarcely believe that the paltry quirks which are faintly heard through a storm of coughing, and which do not impose on the plainest country gentleman, can proceed from the same sharp and vigorous intellect which had excited their admiration under the same roof and on the same day."

"How great a part the Roman Catholic ecclesiastics subsequently had in the abolition of villenage we learn from the unexceptionable testimony of Sir Thomas Smith, one of the ablest Protestant counsellors of Elizabeth. When the dying slaveholder asked for the last sacraments, his spiritual attendants regularly adjured him, as he loved his soul, to emancipate his brethren for whom Christ had died. So successfully had the Church used her formidable machinery that, before the Reformation came, she had enfranchised almost all the bondmen in the kingdom except her own, who, to do her justice, seem to have been very tenderly treated."

"I am quite ready to take the Oriental learning at the valuation of the Orientalists themselves. I have never found one among them who could deny that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia."

"I believe that no country ever stood so much in need of a code of laws as India; and I believe also that there never was a country in which the want might so easily be supplied. I said that there were many points of analogy between the state of that country after the fall of the Mogul power and the state of Europe after the fall of the Roman empire. In one respect the analogy is very striking. As there were in Europe then, so there are in India now, several systems of law widely differing from each other, but coexisting and coequal. The indigenous population has its own laws. Each of the successive race of conquerors has brought with it its own peculiar jurisprudence: the Mussulman his Koran and the innumerable commentators on the Koran; the Englishman his Statute Book and his Term Reports. As there were established in Italy, at one and the same time, the Roman Law, the Lombard Law, the Riparian Law, the Bavarian Law, and the Salic Law, so we have now in our Eastern empire Hindoo Law, Mahometan Law, Parsee Law, English Law, perpetually mingling with each other and disturbing each other, varying with the person, varying with the place. In one and the same cause the process and pleadings are in the fashion of one nation, the judgment is according to the laws of another. An issue is evolved according to the rules of Westminster and decided according to those of Benares. The only Mahometan book in the nature of a code is the Koran; the only Hindoo book, the Institutes. Everybody who knows those books knows that they provide for a very small part of the cases which must arise in every community. All beyond them is comment and tradition. Our regulations in civil matters do not define rights, but merely establish remedies. If a point of Hindoo law arises, the Judge calls on the Pundit for an opinion. If a point of Mahometan law arises, the Judge applies to the Cauzee. What the integrity of these functionaries is, we may learn from Sir William Jones. That eminent man declared that he could not answer it to his conscience to decide any point of law on the faith of a Hindoo expositor. Sir Thomas Strange confirms this declaration. Even if there were no suspicion of corruption on the part of the interpreters of the law, the science which they profess is in such a state of confusion that no reliance can be placed on their answers."

"Horace has prettily compared poems to those paintings of which the effect varies as the spectator changes his stand. The same remark applies with at least equal justice to speeches. They must be read with the temper of those to which they are addressed, or they must necessarily appear to offend against the laws of taste and reason; as the finest picture seen in a light different from that for which it was designed, will appear only fit for a sign. This is perpetually forgotten by those who criticize oratory. Because they are reading at leisure, pausing at every line, reconsidering every argument, they forget that the hearers were hurried from point to point too rapidly to detect the fallacies through which they were conducted; that they had no time to disentangle sophisms, or to notice slight inaccuracies of expression; that elaborate excellence, either of reasoning or of language, would have been absolutely thrown away. To recur to the analogy of the sister art, these connoisseurs examine a panorama through a microscope, and quarrel with a scene-painter because he does not give to his work the exquisite finish of Gerard Dow."

"I affirm, then, that there exists in the United States a slave-trade, not less odious or demoralizing, nay, I do in my conscience believe, more odious and more demoralizing, than that which is carried on between Africa and Brazil. North Carolina and Virginia are to Louisiana and Alabama what Congo is to Rio Janeiro. The slave States of the Union are divided into two classes, the breeding States, where the human beasts of burden increase and multiply and become strong for labour, and the sugar and cotton States, to which those beasts of burden are sent to be worked to death. To what an extent the traffic in man is carried on we may learn by comparing the census of 1830 with the census of 1840. North Carolina and Virginia are, as I have said, great breeding States. During the ten years from 1830 to 1840 the slave population of North Carolina was almost stationary. The slave population of Virginia positively decreased. Yet both in North Carolina and Virginia propagation was during these ten years going on fast. What then became of the surplus? Look to the returns from the Southern States, from the States whose produce the right honourable Baronet proposes to admit with reduced duty or with no duty at all; and you will see. You will find that the increase in the breeding States was barely sufficient to meet the demand of the consuming States. In Louisiana, for example, where we know that the negro population is worn down by cruel toil, and would not if left to itself keep up its numbers, there were in 1830 one hundred and seven thousand slaves; in 1840 one hundred and seventy thousand. In Alabama the slave population during these ten years much more than doubled; it rose from one hundred and seventeen thousand to two hundred and fifty-three thousand. In Mississippi it actually tripled: it rose from sixty-five thousand to one hundred and ninety-five thousand. So much for the extent of this slave-trade."

"I believe, Sir, that it is the right and the duty of the State to provide means of education for the common people. This proposition seems to me to be implied in every definition that has ever yet been given of the functions of a government. About the extent of those functions there has been much difference of opinion among ingenious men. There are some who hold that it is the business of a government to meddle with every part of the system of human life, to regulate trade by bounties and prohibitions, to regulate expenditure by sumptuary laws, to regulate literature by a censorship, to regulate religion by an inquisition. Others go to the opposite extreme, and assign to government a very narrow sphere of action. But the very narrowest sphere that ever was assigned to governments by any school of political philosophy is quite wide enough for my purpose. On one point all the disputants are agreed. They unanimously acknowledge that it is the duty of every government to take order for giving security to the persons and property of the members of the government."

"I cannot refrain, however, from saying a few words upon the translations of the Divine Comedy. Boyd’s is as tedious and languid as the original is rapid and forcible. The strange measure which he has chosen, and, for aught I know, invented, is most unfit for such a work. Translations ought never to be written in a verse which requires much command of rhyme. The stanza becomes a bed of Procrustes, and the thoughts of the unfortunate author are alternately racked and curtailed to fit their new receptacle. The abrupt and yet consecutive style of Dante suffers more than that of any other poet by a version diffuse in style and divided into paragraphs—for they deserve no other name—of equal length. Nothing can be said in favour of Hayley’s attempt, but that it is better than Boyd’s. His mind was a tolerable specimen of filigree work,—rather elegant, and very feeble. All that can be said for his best works is that they are neat. All that can be said against his worst is that they are stupid. He might have translated Metastasio tolerably. But he was utterly unable to do justice to the"

"I don't mind your thinking slowly; I mind your publishing faster than you think."

"I say, therefore, that the education of the people is not only a means, but the best means, of obtaining that which all allow to be a chief end of government; and, if this be so, it passes my faculties to understand how any man can gravely contend that government has nothing to do with the education of the people."

"I have long been convinced that institutions purely democratic must, sooner or later, destroy liberty, or civilization, or both…. I have not the smallest doubt that, if we had a purely democratic government here, the effect would be the same [as in France in 1848]. Either the poor would plunder the rich, and civilization would perish; or order and property would be saved by a strong military government, and liberty would perish. You may think that your country enjoys an exemption from these evils. I will frankly tell you that I am of a very different opinion. Your fate I believe to be certain, though it is deferred by a physical cause…. The day will come when in the State of New York, a multitude of people, none of whom has had more than half a breakfast, or expects to have more than half a dinner, will choose a legislature. Is it possible to doubt what sort of legislature will be chosen? On one side is a statesman preaching patience, respect for vested rights, strict observance of public faith. On the other is a demagogue ranting about the tyranny of capitalists and usurers, and asking why anybody should be permitted to drink champagne and to ride in a carriage while thousands of honest folks are in want of necessaries? Which of the two candidates is likely to be preferred by a working man who hears his children cry for more bread?… There is nothing to stop you. Your Constitution is all sail and no anchor."

"I have not the Chancellor’s encyclopedic mind. He is indeed a kind of semi-Solomon. He half knows everything, from the cedar to the hyssop."

"I shall cheerfully bear the reproach of having descended below the dignity of history if I can succeed in placing before the English of the nineteenth century a true picture of the life of their ancestors."

"I shall not be satisfied unless I produce something that shall for a few days supersede the last fashionable novel on the tables of young ladies."

"I would rather be a poor man in a garret with plenty of books than a king who did not love reading."

"I would hope that there may yet appear a writer who may despise the present narrow limits, and assert the rights of history over every part of her natural domain. Should such a writer engage in that enterprise, in which I cannot but consider Mr. Mitford as having failed, he will record, indeed, all that is interesting and important in military and political transactions; but he will not think anything too trivial for the gravity of history which is not too trivial to promote or diminish the happiness of man. He will portray in vivid colours the domestic society, the manners, the amusements, the conversation, of the Greeks. He will not disdain to discuss the state of agriculture, of the mechanical arts, and of the conveniences of life. The progress of painting, of sculpture, and of architecture, will form an important part of his plan. But, above all, his attention will be given to the history of that splendid literature from which has sprung all the strength, the wisdom, the freedom, and the glory of the western world."

"I turn with pleasure from these wretched performances to Mr. Cary’s translation. It is a work which well deserves a separate discussion, and on which, if this article were not already too long, I could dwell with great pleasure. At present I will only say that there is no other version in the world which so fully proves that the translator is himself a man of poetical genius. Those who are ignorant of the Italian language should read it to become acquainted with the Divine Comedy. Those who are most intimate with Italian literature should read it for its original merits; and I believe that they will find it difficult to determine whether the author deserve; most praise for his intimacy with the language of Dante, or for his extraordinary mastery over his own."

"I would rather be poor in a cottage full of books than a king without the desire to read"

"If a man, such as we are supposing, should write the history of England, he would assuredly not omit the battles, the sieges, the negotiations, the seditions, the ministerial changes. But with these he would intersperse the details which are the charm of historical romances. At Lincoln Cathedral there is a beautiful painted window, which was made by an apprentice out of the pieces of glass which had been rejected by his master. It is so far superior to every other in the church, that, according to the tradition, the vanquished artist killed himself from mortification. Sir Walter Scott, in the same manner, has used those fragments of truth which historians have scornfully thrown behind them in a manner which may well excite their envy. He has constructed out of their gleanings works which, even considered as histories, are scarcely less valuable than theirs."

"If ever Shakespeare rants, it is not when his imagination is hurrying him along, but when he is hurrying his imagination along,—when his mind is for a moment jaded,—when, as was said of Euripides, he resembles a lion, who excites his own fury by lashing himself with his tail. What happened to Shakespeare from the occasional suspension of his powers happened to Dryden from constant impotence. He, like his confederate Lee, had judgment enough to appreciate the great poets of the preceding age, but not judgment enough to shun competition with them. He felt and admired their wild and daring sublimity. That it belonged to another age than that in which he lived, and required other talents than those which he possessed, that in aspiring to emulate it he was wasting in a hopeless attempt powers which might render him pre-eminent in a different career, was a lesson which he did not learn till late. As those knavish enthusiasts, the French prophets, courted inspiration by mimicking the writhings, swoonings, and gaspings which they considered as its symptoms, he attempted, by affected fits of poetical fury, to bring on a real paroxysm; and, like them, he got nothing but distortions for his pains."

"If any person had told the Parliament which met in terror and perplexity after the crash of 1720 that in 1830 the wealth of England would surpass all their wildest dreams, that the annual revenue would equal the principal of that debt which they considered an intolerable burden, that for one man of £10,000 then living there would be five men of £50,000, that London would be twice as large and twice as populous, and that nevertheless the rate of mortality would have diminished to one half of what it then was, that the post-office would bring more into the exchequer than the excise and customs had brought in together under Charles II, that stage coaches would run from London to York in 24 hours, that men would be in the habit of sailing without wind, and would be beginning to ride without horses, our ancestors would have given as much credit to the prediction as they gave to Gulliver's Travels."

"If it were possible that a people brought up under an intolerant and arbitrary system could subvert that system without acts of cruelty and folly, half the objections to despotic power would be removed. We should, in that case, be compelled to acknowledge that it at least produces no pernicious effects on the intellectual and moral character of a nation. We deplore the outrages which accompany revolutions. But the more violent the outrages the more assured we feel that a revolution was necessary. The violence of those outrages will always be proportioned to the ferocity and ignorance of the people; and the ferocity and ignorance of the people will be proportioned to the oppression and degradation under which they have been accustomed to live. Thus it was in our civil war. The heads of the church and state reaped only that which they had sown. The government had prohibited free discussion; it had done its best to keep the people unacquainted with their duties and their rights. The retribution was just and natural. If our rulers suffered from popular ignorance, it was because they had themselves taken away the key of knowledge. If they were assailed with blind fury, it was because they had exacted an equally blind submission."

"If Mr. Gladstone has made out, as he conceives, an imperative necessity for a State Religion, much more has he made it out to be imperatively necessary that every army should, in its collective capacity, profess a religion. Is he prepared to adopt this consequence?"

"If I were convinced that the great body of the middle class in England look with aversion on monarchy and aristocracy, I should be forced, much against my will, to come to this conclusion, that monarchical and aristocratical institutions are unsuited to my country. Monarchy and aristocracy, valuable and useful as I think them, are still valuable and useful as means, and not as ends. The end of government is the happiness of the people; and I do not conceive that, in a country like this, the happiness of the people can be promoted by a form of government in which the middle classes place no confidence, and which exists only because the middle classes have no organ by which to make their sentiments known. But, Sir, I am fully convinced that the middle classes sincerely wish to uphold the Royal prerogatives and the constitutional rights of the Peers."

"If revelation speaks on the subject of the origin of evil, it speaks only to discourage dogmatism and temerity. In the most ancient, the most beautiful, and the most profound of all works on the subject, the Book of Job, both the sufferer who complains of the divine government and the injudicious advisers who attempt to defend it on wrong principles are silenced by the voice of supreme wisdom, and reminded that the question is beyond the reach of the human intellect. St. Paul silences the supposed objector who strives to force him into controversy in the same manner. The church has been ever since the apostolic times agitated by this question, and by a question which is inseparable from it, the question of fate and free-will. The greatest theologians and philosophers have acknowledged that these things were too high for them, and have contented themselves with hinting at what seemed to be the most probable solution. What says Johnson? All our effort ends in belief that for the evils of life there is some good reason, and in confession that the reason cannot be found. What says Paley? Of the origin of evil no universal solution has been discovered; I mean, no solution which reaches to all cases of complaint. The consideration of general laws, although it may concern the question of the origin of evil very nearly, which I think it does, rests in views disproportionate to our faculties, and in a knowledge which we do not possess. It serves rather to account for the obscurity of the subject than to supply us with distinct answers to our difficulties."

"If it be admitted that on the institution of property the well-being of society depends, it follows surely that it would be madness to give supreme power in the state to a class which would not be likely to respect that institution. And if this be conceded, it seems to me to follow that it would be madness to grant the prayer of this petition. I entertain no hope that if we place the government of the kingdom in the hands of the majority of the males of one-and-twenty told by the head, the institution of property will be respected. If I am asked why I entertain no such hope, I answer, Because the hundreds of thousands of males of twenty-one who have signed this petition tell me to entertain no such hope; because they tell me that if I trust them with power the first use which they make of it will be to plunder every man in the kingdom who has a good coat on his back and a good roof over his head."

"If the doctrine that men always act from self-interest be laid down in any other sense than this—if the meaning of the word self-interest be narrowed so as to exclude any one of the motives which may by possibility act on any human being, the proposition ceases to be identical: but at the same time it ceases to be true."

"If such arguments are to pass current, it will be easy to prove that there never was such a thing as religious persecution since the creation. For there never was a religious persecution in which some odious crime was not, justly or unjustly, said to be obviously deducible from the doctrines of the persecuted party. We might say that the Cæsars did not persecute the Christians; that they only punished men who were charged, rightly or wrongly, with burning Rome, and with committing the foulest abominations in secret assemblies; and that the refusal to throw frankincense on the altar of Jupiter was not the crime, but only evidence of the crime. We might say that the massacre of St. Bartholomew was intended to extirpate, not a religious sect, but a political party. For, beyond all doubt, the proceedings of the Huguenots, from the conspiracy of Amboise to the battle of Moncontour, had given much more trouble to the French monarchy than the Catholics have ever given to the English monarchy since the Reformation; and that too with much less excuse."

"If there be any truth established by the universal experience of nations, it is this, that to carry the spirit of peace into war is a weak and cruel policy. The time for negotiation is the time for deliberation and delay. But when an extreme case calls for that remedy which is in its own nature most violent, it is idle to think of mitigating and diluting. Languid war can do nothing which negotiation or submission will not do better: and to act on any other principle is not to save blood and money, but to squander them."

"If the Sunday had not been observed as a day of rest during the last three centuries, I have not the slightest doubt that we should have been at this moment a poorer people and less civilized."

"If we consider merely the subtlety of disquisition, the force of imagination, the perfect energy and elegance of expression, which characterize the great works of Athenian history, we must pronounce them intrinsically most valuable; but what shall we say when we reflect that from hence have sprung directly or indirectly all the noblest creations of the human intellect; that from hence were the vast accomplishments and the brilliant fancy of Cicero; the withering fire of Juvenal; the plastic imagination of Dante; the humour of Cervantes; the comprehension of Bacon; the wit of Butler; the supreme and universal excellence of Shakespeare? All the triumphs of truth and genius over prejudice and power, in every country and in every age, have been the triumphs of Athens. Wherever a few great minds have made a stand against violence and fraud, in the cause of liberty and reason, there has been her spirit in the midst of them; inspiring, encouraging, consoling;—by the lonely lamp of Erasmus; by the restless bed of Pascal; in the tribune of Mirabeau; in the cell of Galileo; on the scaffold of Sidney. But who shall estimate her influence on private happiness? Who shall say how many thousands have been made wiser, happier, and better, by those pursuits in which she has taught mankind to engage: to how many the studies which took their rise from her have been wealth in poverty,—liberty in bondage,—health in sickness,—society in solitude? Her power is indeed manifested at the bar, in the senate, in the field of battle, in the schools of philosophy. But these are not her glory. Wherever literature consoles sorrow, or assuages pain,—wherever it brings gladness to eyes which fail with wakefulness and tears, and ache for the dark house and the long sleep,—there is exhibited, in its noble form, the immortal influence of Athens."

"If we went at large into this most interesting subject we should fill volumes. We will, therefore, at present advert to only one important part of the policy of the Church of Rome. She thoroughly understands, what no other church has ever understood, how to deal with enthusiasts. In some sects, particularly in infant sects, enthusiasm is suffered to be rampant. In other sects, particularly in sects long established and richly endowed, it is regarded with aversion. The Catholic Church neither submits to enthusiasm nor proscribes it, but uses it. She considers it as a great moving force, which in itself, like the muscular power of a fine horse, is neither good nor evil, but which may be so directed as to produce great good or great evil; and she assumes the direction to herself. It would be absurd to run down a horse like a wolf. It would be still more absurd to let him run wild, breaking fences and trampling down passengers. The rational course is to subjugate his will without impairing his vigour, to teach him to obey the rein, and then to urge him to full speed. When once he knows his master he is valuable in proportion to his strength and spirit. Just such has been the system of the Church of Rome with regard to enthusiasts. She knows that when religious feelings have obtained the complete empire of the mind they impart a strange energy, that they raise men above the dominion of pain and pleasure, that obloquy becomes glory, that death itself is contemplated only as the beginning of a higher and happier life. She knows that a person in this state is no object of contempt. He may be vulgar, ignorant, visionary, extravagant; but he will do and suffer things which it is for her interest that somebody should do and suffer, yet from which calm and sober-minded men would shrink. She accordingly enlists him in her service, assigns to him some forlorn hope, in which intrepidity and impetuosity are more wanted than judgment and self-command, and sends him forth with her benedictions and her applause."

"If, indeed, all men reasoned in the same manner on the same data, and always did what they thought it their duty to do, this mode of dispensing punishment might be extremely judicious. But as people who agree about premises often disagree about conclusions, and as no man in the world acts up to his own standard of right, there are two enormous gaps in the logic by which alone penalties for opinions can be defended. The doctrine of reprobation, in the judgment of many very able men, follows by syllogistic necessity from the doctrine of election. Others conceive that the Antinomian heresy directly follows from the doctrine of reprobation; and it is very generally thought that licentiousness and cruelty of the worst description are likely to be the fruits, as they often have been the fruits, of Antinomian opinions. This chain of reasoning, we think, is as perfect in all its parts as that which makes out a Papist to be necessarily a traitor. Yet it would be rather a strong measure to hang all the Calvinists, on the ground that, if they were spared, they would infallibly commit all the atrocities of Matthias and Knipperdoling. For, reason the matter as we may, experience shows us that a man may believe in election without believing in reprobation, that he may believe in reprobation without being an Antinomian, and that he may be an Antinomian without being a bad citizen. Man, in short, is so inconsistent a creature that it is impossible to reason from his belief to his conduct, or from one part of his belief to another."

"If, however, there be any form of government which in all ages and all nations has always been, and must always be, pernicious, it is certainly that which Mr. Mitford, on his usual principle of being wiser than all the rest of the world, has taken under his especial patronage,—pure oligarchy."

"In a barbarous age the imagination exercises a despotic power. So strong is the perception of what is unreal that it often overpowers all the passions of the mind and all the sensations of the body. At first, indeed, the phantasm remains undivulged, a hidden treasure, a wordless poetry, an invisible painting, a silent music, a dream of which the pains and pleasures exist to the dreamer alone, a bitterness which the heart only knoweth, a joy with which a stranger intermeddleth not. The machinery by which ideas are to be conveyed from one person to another is as yet rude and defective. Between mind and mind there is a great gulf. The imitative arts do not exist, or are in their lower state. But the actions of men amply prove that the faculty which gives birth to those arts is morbidly active. It is not yet the inspiration of poets and sculptors; but it is the amusement of the day, the terror of the night, the fertile source of wild superstitions. It turns the clouds into gigantic shapes and the winds into doleful voices. The belief which springs from it is more absolute and undoubting than any which can be derived from evidence. It resembles the faith which we repose in our own sensations. Thus, the Arab, when covered with wounds, saw nothing but the dark eyes and the green kerchief of a beckoning Houri. The Northern warrior laughed in the pangs of death when he thought of the mead of Valhalla."

"In an age in which there are so few readers that a writer cannot subsist on the sum arising from the sale of his works, no man who has not an independent fortune can devote himself to literary pursuits unless he is assisted by patronage. In such an age, accordingly, men of letters too often pass their lives in dangling at the heels of the wealthy and powerful; and all the faults which dependence tends to produce, pass into their character. They become the parasites and slaves of the great. It is melancholy to think how many of the highest and most exquisitely formed of human intellects have been condemned to the ignominious labour of disposing the commonplaces of adulation in new forms and brightening them into new splendour. Horace invoking Augustus in the most enthusiastic language of religious veneration. Statius flattering a tyrant, and the minion of a tyrant, for a morsel of bread, Ariosto versifying the whole genealogy of a niggardly patron, Tasso extolling the heroic virtues of the wretched creature who locked him up in a mad-house, these are but a few of the instances which might easily be given of the degradation to which those must submit who, not possessing a competent fortune, are resolved to write when there are scarcely any who read."

"In a rude state of society men are children with a greater variety of ideas. It is therefore in such a state of society that we may expect to find the poetical temperament in its highest perfection. In an enlightened age there will be much intelligence, much science, much philosophy, abundance of just classification and subtle analysis, abundance of wit and eloquence, abundance of verses, and even of good ones; but little poetry. Men will judge and compare; but they will not create. They will talk about the old poets, and comment on them, and to a certain degree enjoy them. But they will scarcely be able to conceive the effect which poetry produced on their ruder ancestors,—the agony, the ecstasy, the plenitude of belief. The Greek Rhapsodist, according to Plato, could scarce recite Homer without falling into convulsions. The Mohawk hardly feels the scalping-knife while he shouts his death-song. The power which the ancient bards of Wales and Germany exercised over their auditors seems to modern readers almost miraculous. Such feelings are very rare in a civilized community, and most rare among those who participate most in its improvements. They linger longest among the peasantry."

"In England, it not unfrequently happens that a tinker or coal-heaver hears a sermon or falls in with a tract which alarms him about the state of his soul. If he be a man of excitable nerves and strong imagination he thinks himself given over to the Evil Power. He doubts whether he has not committed the unpardonable sin. He imputes every wild fancy that springs up in his mind to the whisper of a fiend. His sleep is broken by dreams of the great judgment-seat, the open books, and the unquenchable fire. If, in order to escape from these vexing thoughts, he flies to amusement or to licentious indulgence, the delusive relief only makes his misery darker and more hopeless. At length a turn takes place. He is reconciled to his offended Maker. To borrow the fine imagery of one who had himself been thus tried, he emerges from the Valley of the Shadow of Death, from the dark land of gins and snares, of quagmires and precipices, of evil spirits and ravenous beasts. The sunshine is on his path. He ascends the Delectable Mountains, and catches from their summit a distant view of the shining city which is the end of his pilgrimage. Then arises in his mind a natural and surely not a censurable desire to impart to others the thoughts of which his own heart is full, to warn the careless, to comfort those who are troubled in spirit. The impulse which urges him to devote his whole life to the teaching of religion is a strong passion in the guise of a duty. He exhorts his neighbours; and, if he be a man of strong parts, he often does so with great effect. He pleads as if he were pleading for his life, with tears, and pathetic gestures, and burning words; and he soon finds with delight, not perhaps wholly unmixed with the alloy of human infirmity, that his rude eloquence rouses and melts hearers who sleep very composedly while the rector preaches on the apostolical succession. Zeal for God, love for his fellow-creatures, pleasure in the exercise of his newly-discovered powers, impel him to become a preacher. He has no quarrel with the establishment, no objection to its formularies, its government, or its vestments. He would gladly be admitted among its humblest ministers. But, admitted or rejected, he feels that his vocation is determined. His orders have come down to him, not through a long and doubtful series of Arian and Papist bishops, but direct from on high. His commission is the same that on the Mountain of Ascension was given to the Eleven. Nor will he, for lack of human credentials, spare to deliver the glorious message with which he is charged by the true Head of the Church. For a man thus minded there is within the pale of the establishment no place. He has been at no college; he cannot construe a Greek author or write a Latin theme; and he is told that if he remains in the communion of the Church he must do so as a hearer, and that if he is resolved to be a teacher he must begin by being a schismatic. His choice is soon made. He harangues on Tower Hill or in Smithfield. A congregation is formed. A license is obtained. A plain brick building, with a desk and benches, is run up, and named Ehenezer or Bethel. In a few weeks the Church has lost forever a hundred families not one of which entertained the least scruple about her articles, her liturgy, her government, or her ceremonies."