Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

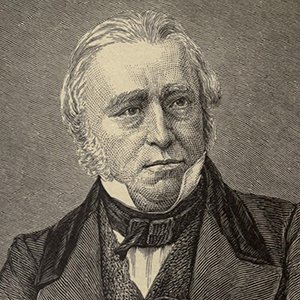

Thomas Macaulay, fully Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay

British Poet,Historian, Essayist, Biographer, Secretary of War, Paymaster-General and Whig Politician

"In every age the Church has been cautioned against this fatal and impious rashness by its most illustrious members,—by the fervid Augustin, by the subtle Aquinas, by the all-accomplished Pascal. The warning has been given in vain. That close alliance which, under the disguise of the most deadly enmity, has always subsisted between fanaticism and atheism is still unbroken. At one time the cry was, If you hold that the earth moves round the sun, you deny the truth of the Bible. Popes, conclaves, and religious orders rose up against the Copernican heresy. But, as Pascal said, they could not prevent the earth from moving, or themselves from moving along with it."

"In history this error is far more disgraceful. Indeed, there is no fault which so completely ruins a narrative in the opinion of a judicious reader. We know that the line of demarcation between good and bad men is so faintly marked as often to elude the most careful investigation of those who have the best opportunities for judging. Public men, above all, are surrounded with so many temptations and difficulties that some doubt must almost always hang over their real dispositions and intentions. The lives of Pym, Cromwell, Monk, Clarendon, Marlborough, Burnet, Walpole, are well known to us. We are acquainted with their actions, their speeches, their writings; we have abundance of letters and well-authenticated anecdotes relating to them; yet what candid man will venture very positively to say which of them were honest and which of them were dishonest men? It appears easier to pronounce decidedly upon the great characters of antiquity, not because we have greater means of discovering truth, but simply because we have less means of detecting error. The modern historians of Greece have forgotten this. Their heroes and villains are as consistent in all their sayings and doings as the cardinal virtues and the deadly sins in an allegory. We should as soon expect a good action from giant Slay-good in Bunyan as from Dionysius; and a crime of Epaminondas would seem as incongruous as a faux-pas of the grave and comely damsel called Discretion, who answered the bell at the door of the house Beautiful."

"In every age the vilest specimens of human nature are to be found among demagogues."

"In no form of government is there an absolute identity of interest between the people and their rulers. In every form of government, the rulers stand in some awe of the people. The fear of resistance and the sense of shame operate in a certain degree on the most absolute kings and the most illiberal oligarchies. And nothing but the fear of resistance and the sense of shame preserves the freedom of the most democratic communities from the encroachments of their annual and biennial delegates."

"In every other part of Europe, a large and powerful privileged class trampled on the people and defied the government. But, in the most flourishing parts of Italy, the feudal nobles were reduced to comparative insignificance. In some districts they took shelter under the protection of the powerful commonwealths which they were unable to oppose, and gradually sank into the mass of burghers. In other places they possessed great influence; but it was an influence widely different from that which was exercised by the aristocracy of any Transalpine kingdom. They were not petty princes, but eminent citizens. Instead of strengthening their fastnesses among the mountains, they embellished their palaces in the market-place. The state of society in the Neapolitan dominions, and in some parts of the Ecclesiastical State, more nearly resembled that which existed in the great monarchies of Europe. But the governments of Lombardy and Tuscany, through all their revolutions, preserved a different character. A people when assembled in a town is far more formidable to its rulers than when dispersed over a wide extent of country. The most arbitrary of the Cæsars found it necessary to feed and divert the inhabitants of their unwieldy capital at the expense of the provinces. The citizens of Madrid have more than once besieged their sovereign in his own palace and extorted from him the most humiliating concessions. The Sultans have often been compelled to propitiate the furious rabble of Constantinople with the head of an unpopular vizier. From the same causes there was a certain tinge of democracy in the monarchies and aristocracies of Northern Italy."

"In no modern society, not even in England during the reign of Elizabeth, has there been so great a number of men eminent at once in literature and in the pursuits of active life, as Spain produced during the sixteenth century. Almost every distinguished writer was also distinguished as a soldier or a politician. Boscan bore arms with high reputation. Garcilaso de Vega, the author of the sweetest and most graceful pastoral poem of modern times, after a short but splendid military career, fell sword in hand at the head of a storming party. Alonzo de Ercilla bore a conspicuous part in that war of Arauco which he afterwards celebrated in one of the best heroic poems that Spain has produced. Hurtado de Mendoza, whose poems have been compared to those of Horace, and whose charming little novel is evidently the model of Gil Blas, has been handed down to us by history as one of the sternest of those iron proconsuls who were employed by the House of Austria to crush the lingering public spirit of Italy. Lope sailed in the Armada; Cervantes was wounded at Lepanto."

"In order that he might rob a neighbour whom he had promised to defend, black men fought on the coast of Coromandel and red men scalped each other by the great lakes of North America."

"In his tragedies he trusted, and not altogether without reason, to his diction and his versification. It was on this account, in all probability, that he so eagerly adopted, and so reluctantly abandoned, the practice of rhyming in his plays. What is unnatural appears less unnatural in that species of verse than in lines which approach more nearly to common conversation; and in the management of the heroic couplet Dryden has never been equalled. It is unnecessary to urge any arguments against a fashion now universally condemned. But it is worthy of observation that, though Dryden was deficient in that talent which blank verse exhibits to the greatest advantage, and was certainly the best writer of heroic rhyme in our language, yet the plays which have, from the time of their first appearance, been considered as his best, are in blank verse. No experiment can be more decisive."

"In our time, the audience of a member of Parliament is the nation. The three or four hundred persons who may be present while a speech is delivered may be pleased or disgusted by the voice and action of the orator; but, in the reports which are read the next day by hundreds of thousands, the difference between the noblest and the meanest figure, between the richest and the shrillest tones, between the most graceful and the most uncouth gesture, altogether vanishes. A hundred years ago scarcely any report of what passed within the walls of the House of Commons was suffered to get abroad. In those times, therefore, the impression which a speaker might make on the persons who actually heard him was everything. His fame out of doors depended entirely on the report of those who were within the doors. In the Parliaments of that time, therefore, as in the ancient commonwealths, those qualifications which enhance the immediate effect of a speech were far more important ingredients in the composition of an orator than at present. All those qualifications Pitt possessed in the highest degree. On the stage he would have been the finest Brutus or Coriolanus ever seen."

"In process of time the instruments by which the imagination works are brought to perfection. Men have not more imagination than their rude ancestors. We strongly suspect that they have much less. But they produce better works of imagination. Thus, up to a certain period the diminution of the poetical powers is far more than compensated by the improvement of all the appliances and means of which those powers stand in need. Then comes the short period of splendid and consummate excellence. And then, from causes against which it is vain to struggle, poetry begins to decline. The progress of language, which was at first favourable, becomes fatal to it, and, instead of compensating for the decay of the imagination, accelerates that decay, and renders it more obvious. When the adventurer in the Arabian tale anointed one of his eyes with the contents of the magical box, all the riches of the earth, however widely dispersed, however sacredly concealed, became visible to him. But when he tried the experiment on both eyes he was struck with blindness. What the enchanted elixir was to the sight of the body, language is to the sight of the imagination. At first it calls up a world of glorious illusions; but when it becomes too copious it altogether destroys the visual power."

"In Plato's opinion, man was made for philosophy; in Bacon's opinion, philosophy was made for man."

"In such a state of society as that which existed all over Europe during the middle ages, very slight checks sufficed to keep the sovereign in order. His means of corruption and intimidation were very scanty. He had little money, little patronage, no military establishment. His armies resembled juries. They were drawn out of the mass of the people: they soon returned to it again: and the character which was habitual prevailed over that which was occasional. A campaign of forty days was too short, the discipline of a national militia too lax, to efface from their minds the feelings of civil life. As they carried to the camp the sentiments and interests of the farm and the shop, so they carried back to the farm and the shop the military accomplishments which they had acquired in the camp. At home the soldier learned how to value his rights, abroad how to defend them."

"In so far as the laws of nature produce evil, they are clearly not benevolent. They may produce much good. But why is this good mixed with evil? The most subtle and powerful intellects have been labouring for centuries to solve these difficulties. The true solution, we are inclined to think, is that which has been rather suggested, than developed, by Paley and Butler. But there is not one solution which will not apply quite as well to the evils of over-population as to any other evil. Many excellent people think that it is presumptuous to meddle with such high questions at all, and that, though there doubtless is an explanation, our faculties are not sufficiently enlarged to comprehend that explanation. This mode of getting rid of the difficulty, again, will apply quite as well to the evils of over-population as to any other evils. We are quite sure that those who humbly confess their inability to expound the great enigma act more rationally and more decorously than Mr. Sadler, who tells us, with the utmost confidence, which are the means and which the ends, which the exceptions and which the rules, in the government of the universe;—who consents to bear a little evil without denying the divine benevolence, but distinctly announces that a certain quantity of dry weather or stormy weather would force him to regard the Deity as the tyrant of his creatures."

"In that temple of silence and reconciliation where the enmities of twenty generations lie buried, in the great Abbey which has during many ages afforded a quiet resting-place to those whose minds and bodies have been shattered by the contentions of the Great Hall."

"In some countries, in our own for example, there has been an interval between the downfall of the creative school and the rise of the critical, a period during which imagination has been in its decrepitude and taste in its infancy. Such a revolutionary interregnum as this will be deformed by every species of extravagance."

"In the early contributions of Addison to the Tatler his peculiar powers were not fully exhibited. Yet, from the first, his superiority to all his coadjutors was evident. Some of his later Tatlers are fully equal to anything that he ever wrote. Among the portraits we most admire Tom Folio, Ned Softly, and the Political Upholsterer. The proceedings of the Court of Honour, the Thermometer of Zeal, the story of the Frozen Words, the Memoirs of the Shilling, are excellent specimens of that ingenious and lively species of fiction in which Addison excelled all men. There is one still better paper of the same class. But though that paper, a hundred and thirty-three years ago, was probably thought as edifying as one of Smalridge’s sermons, we dare not indicate it to the squeamish readers of the nineteenth century."

"In the meantime, the credulous public pities and pampers a nuisance which requires only the treadmill and the whip. This art, often successful when employed by dunces, gives irresistible fascination to works which possess intrinsic merit. We are always desirous to know something of the character and situation of those whose writings we have perused with pleasure. The passages in which Milton has alluded to his own circumstances are perhaps read more frequently, and with more interest, than any other lines in his poems. It is amusing to observe with what labour critics have attempted to glean from the poems of Homer some hints as to his situation and feelings. According to one hypothesis, he intended to describe himself under the name of Demodocus. Others maintain that he was the identical Phemius whose life Ulysses spared. This propensity of the human mind explains, I think, in a great degree, the extensive popularity of a poet whose works are little else than the expression of his personal feelings."

"In the Anecdotes of Painting, [Walpole] states, very truly, that the art declined after the commencement of the civil wars. He proceeds to inquire why this happened. The explanation, we should have thought, would have been easily found. He might have mentioned the loss of the most munificent and judicious patron that the fine arts ever had in England, the troubled state of the country, the distressed condition of many of the aristocracy, perhaps also the austerity of the victorious party. These circumstances, we conceive, fully account for the phenomenon. But this solution was not odd enough to satisfy Walpole. He discovers another cause for the decline of the art,—the want of models. Nothing worth painting, it seems, was left to paint. How picturesque, he exclaims, was the figure of an Anabaptist! as if puritanism had put out the sun and withered the trees; as if the civil wars had blotted out the expression of character and passion from the human lip and brow; as if many of the men whom Vandyke painted had not been living in the time of the Commonwealth, with faces little the worse for wear; as if many of the beauties afterwards portrayed by Lely were not in their prime before the Restoration; as if the garb or the features of Cromwell and Milton were less picturesque than those of the round-faced peers, as like each other as eggs to eggs, who look out from the middle of the periwigs of Kneller."

"In the Mandragola Machiavelli has proved that he completely understood the nature of the dramatic art, and possessed talents which would have enabled him to excel in it. By the correct and vigorous delineation of human nature, it produces interest without a pleasing or skilful plot, and laughter without the least ambition of wit. The lover, not a very delicate or generous lover, and his adviser the parasite, are drawn with spirit. The hypocritical confessor is an admirable portrait. He is, if we mistake not, the original of Father Dominic, the best comic character of Dryden. But old Nicias is the glory of the piece. We cannot call to mind anything that resembles him. The follies which Molière ridicules are those of affectation, not of fatuity. Coxcombs and pedants, not absolute simpletons, are his game. Shakespeare has indeed a vast assortment of fools; but the precise species of which we speak is not, if we remember right, to be found there. Shallow is a fool. But his animal spirits supply, to a certain degree, the place of cleverness. His talk is to that of Sir John what soda-water is to champagne. It has the effervescence, though not the body or the flavour. Slender and Sir Andrew Aguecheek are fools, troubled with an uneasy consciousness of their folly, which, in the latter, produces meekness and docility, and in the former, awkwardness, obstinacy, and confusion. Cloten is an arrogant fool, Osric a foppish fool, Ajax a savage fool, but Nicias is, as Thersites says of Patroclus, a fool positive. His mind is occupied by no strong feeling; it takes every character, and retains none; its aspect is diversified, not by passions, but by faint and transitory semblances of passion, a mock joy, a mock fear, a mock love, a mock pride, which chase each other like shadows over its surface, and vanish as soon as they appear. He is just idiot enough to be an object, not of pity or horror, but of ridicule. He bears some resemblance to poor Calandrino, whose mishaps, as recounted by Boccaccio, have made all Europe merry for more than four centuries. He perhaps resembles still more closely Simon da Villa, to whom Bruno and Buffalmacco promised the love of the Countess Civiliari. Nicias is, like Simon, of a learned profession; and the dignity with which he wears the doctoral fur renders his absurdities infinitely more grotesque. The old Tuscan is the very language for such a being. Its peculiar simplicity gives even to the most forcible reasoning and the most brilliant wit an infantine air, generally delightful, but to a foreign reader sometimes a little ludicrous. Heroes and statesmen seem to lisp when they use it. It becomes Nicias incomparably, and renders all his silliness infinitely more silly."

"In the philosophy of history the moderns have very far surpassed the ancients. It is not, indeed, strange that the Greeks and Romans should not have carried the science of government, or any other experimental science, so far as it has been carried in our time; for the experimental sciences are generally in a state of progression. They were better understood in the seventeenth century than in the sixteenth, and in the eighteenth century than in the seventeenth. But this constant improvement, this natural growth of knowledge, will not altogether account for the immense superiority of the modern writers. The difference is a difference not in degree, but of kind. It is not merely that new principles have been discovered, but that new faculties seem to be exerted. It is not that at one time the human intellect should have made but small progress, and at another time have advanced far; but that at one time it should have been stationary, and at another time constantly proceeding. In taste and imagination, in the graces of style, in the arts of persuasion, in the magnificence of public works, the ancients were at least our equals. They reasoned as justly as ourselves on subjects which required pure demonstration. But in the moral sciences they made scarcely any advance. During the long period which elapsed between the fifth century before the Christian era and the fifteenth after it, little perceptible progress was made. All the metaphysical discoveries of all the philosophers from the time of Socrates to the northern invasion are not to be compared in importance with those which have been made in England every fifty years since the time of Elizabeth. There is not the least reason to believe that the principles of government, legislation, and political economy were better understood in the time of Augustus Cæsar than in the time of Pericles. In our own country, the sound doctrines of trade and jurisprudence have been within the lifetime of a single generation dimly hinted, boldly propounded, defended, systematized, adopted by all reflecting men of all parties, quoted in legislative assemblies, incorporated into laws and treaties."

"In this class three men stand pre-eminent, Cæsar, Cromwell, and Bonaparte. The highest place in this remarkable triumvirate belongs undoubtedly to Cæsar. He united the talents of Bonaparte to those of Cromwell; and he possessed also, what neither Cromwell nor Bonaparte possessed, learning, taste, wit, eloquence, the sentiments and manners of an accomplished gentleman."

"In the name of art as well as in the name of virtue, we protest against the principle that the world of pure comedy is one into which no moral enters. If comedy be an imitation, under whatever conventions, of real life, how is it possible that it can have no reference to the great rule which directs life, and to feelings which are called forth by every incident of life? If what Mr. Charles Lamb says were correct, the inference would be that these dramatists did not in the least understand the very first principles of their craft. Pure landscape-painting into which no light or shade enters, pure portrait-painting into which no expression enters, are phrases less at variance with sound criticism than pure comedy into which no moral enters. But it is not the fact that the world of these dramatists is a world into which no moral enters. Morality constantly enters into that world, a sound morality, and an unsound morality; the sound morality to be insulted, derided, associated with everything mean and hateful; the unsound morality to be set off to every advantage, and inculcated by all methods, direct and indirect."

"In time men began to take more rational and comprehensive views of literature. The analysis of poetry, which, as we have remarked, must at best be imperfect, approaches nearer and nearer to exactness. The merits of the wonderful models of former times are justly appreciated. The frigid productions of a later age are rated at no more than their proper value. Pleasing and ingenious imitations of the manners of the great masters appear. Poetry has a partial revival, a Saint Martin’s Summer, which, after a period of dreariness and decay, greatly reminds us of the splendour of its June. A second harvest is gathered in; though, growing on a spent soil, it has not the heart of the former. Thus, in the present age, Monti has successfully imitated the style of Dante, and something of the Elizabethan inspiration has been caught by several eminent countrymen of our own. But never will Italy produce another Inferno, or England another Hamlet. We look on the beauties of the modern imitations with feelings similar to those with which we see flowers disposed in vases to ornament the drawing-rooms of a capital. We doubtless regard them with pleasure, with greater pleasure, perhaps, because, in the midst of a place ungenial to them, they remind us of the distant spots on which they flourish in spontaneous exuberance. But we miss the sap, the freshness, and the bloom. Or, if we may borrow another illustration from Queen Scheherezade, we would compare the writers of this school to the jewellers who were employed to complete the unfinished windows of the palace of Aladdin. Whatever skill or cost could do was done. Palace and bazaar were ransacked for precious stones. Yet the artists, with all their dexterity, with all their assiduity, and with all their vast means, were unable to produce anything comparable to the wonders which a spirit of a higher order had wrought in a single night."

"In the sense in which we are now using the word correctness, we think that Sit Walter Scott, Mr. Wordsworth, Mr. Coleridge, are far more correct poets than those who are commonly extolled as the models of correctness,—Pope, for example, and Addison. The single description of a moonlight night in Pope’s Iliad contains more inaccuracies than can be found in all the Excursion. There is not a single scene in Cato, in which all that conduces to poetical illusion, all the propriety of character, of language, of situation, is not more grossly violated than in any part of the Lay of the Last Minstrel. No man can think that the Romans of Addison resemble the real Romans so closely as the moss-troopers of Scott resemble the real moss-troopers. Wat Tinlinn and William of Deloraine are not, it is true, persons of so much dignity as Cato. But the dignity of the persons represented has as little to do with the correctness of poetry as with the correctness of painting. We prefer a gipsy by Reynolds to his Majesty’s head on a sign-post, and a Borderer by Scott to a Senator by Addison."

"In what sense, then, is the word correctness used by those who say, with the author of the Pursuits of Literature, that Pope was the most correct of English poets, and that next to Pope came the late Mr. Gifford? What is the nature and value of that correctness, the praise of which is denied to Macbeth, to Lear, and to Othello, and given to Hoole’s translations and to all the Seatonian prize-poems? We can discover no eternal rule, no rule founded in reason and in the nature of things, which Shakespeare does not observe much more strictly than Pope. But if by correctness he meant the conforming to a narrow legislation which, while lenient to the mala in se, multiplies, without the show of a reason, the mala prohibita, if by correctness he meant a strict attention to certain ceremonious observances, which are no more essential to poetry than etiquette to good government, or than the washings of a Pharisee to devotion, then, assuredly, Pope may be a more correct poet than Shakespeare; and, if the code were a little altered, Colley Cibber might be a more correct poet than Pope. But it may well be doubted whether this kind of correctness be a merit, nay, whether it be not an absolute fault."

"In wit, if by wit be meant the power of perceiving analogies between things which appear to have nothing in common, [Lord Bacon] never had an equal, not even Cowley, not even the author of Hudibras. Indeed, he possessed this faculty, or rather this faculty possessed him, to a morbid degree. When he abandoned himself to it without reserve, as he did in the Sapientia Veterum, and at the end of the second book of the De Augmentis, the feats which he performed were not merely admirable, but portentous, and almost shocking. On those occasions we marvel at him as clowns on a fair-day marvel at a juggler, and can hardly help thinking that the devil must be in him…. Yet we cannot wish that Bacon’s wit had been less luxuriant. For, to say nothing of the pleasure which it affords, it was in the vast majority of cases employed for the purpose of making obscure truth plain, of making repulsive truth attractive, of fixing in the mind forever truth which might otherwise have left but a transient impression."

"In wit, properly so called, Addison was not inferior to Cowley or Butler. No single ode of Cowley contains so many happy analogies as are crowded into the lines of Sir Godfrey Kneller; and we would undertake to collect from the Spectators as great a number of ingenious illustrations as can be found in Hudibras. The still higher faculty of invention Addison possessed in still larger measure. The numerous fictions, generally original, often wild and grotesque, but always singularly graceful and happy, which are found in his essays, fully entitle him to the rank of a great poet, a rank to which his metrical compositions give him no claim. As an observer of life, of manners, of all the shades of human character, he stands in the first class. And what he observed he had the art of communicating in two widely different ways. He could describe virtues, vices, habits, whims, as well as Clarendon. But he could do something better. He could call human beings into existence, and make them exhibit themselves. If we wish to find anything more vivid than Addison’s best portraits, we must go either to Shakespeare or to Cervantes."

"Indeed, most of the popular novels which preceded Evelina were such as no lady would have written; and many of them were such as no lady could without confusion own that she had read. The very name of novel was held in horror among religious people. In decent families, which did not profess extraordinary sanctity, there was a strong feeling against all such works. Sir Anthony Absolute, two or three years before Evelina appeared, spoke the sense of the great body of sober fathers and husbands, when he pronounced the circulating library an evergreen tree of diabolical knowledge. This feeling, on the part of the grave and reflecting, increased the evil from which it had sprung. The novelist, having little character to lose, and having few readers among serious people, took without scruple liberties which in our generation seem almost incredible."

"Indeed, the argument which we are considering seems to us to be founded on an entire mistake. There are branches of knowledge with respect to which the law of the human mind is progress. In mathematics, when once a proposition has been demonstrated it is never afterwards contested. Every fresh story is as solid a basis for new superstructure as the original foundation was. Here, therefore, there is a constant addition to the stock of truth. In the inductive sciences, again, the law is progress. Every day furnishes new facts, and thus brings theory nearer and nearer to perfection. There is no chance that either in the purely demonstrative or in the purely experimental sciences the world will ever go back, or even remain stationary. Nobody ever heard of a reaction against Taylor’s theorem, or of a reaction against Harvey’s doctrine of the circulation of the blood."

"Institutions purely democratic must, sooner, or later, destroy liberty or civilization or both."

"Is the love of approbation a stronger motive than the love of wealth? It is impossible to answer this question generally even in the case of an individual with whom we are very intimate. We often say, indeed, that a man loves fame more than money, or money more than fame. But this is said in a loose and popular sense; for there is scarcely a man who would not endure a few sneers for a great sum of money, if he were in pecuniary distress; and scarcely a man, on the other hand, who if he were in flourishing circumstances would expose himself to the hatred and contempt of the public for a trifle. In order, therefore, to return a precise answer even about a single human being, we must know what is the amount of the sacrifice of reputation demanded and of the pecuniary advantage offered, and in what situation the person to whom the temptation is proposed stands at the time. But when the question is propounded generally about the whole species, the impossibility of answering is still more evident. Man differs from man; generation from generation; nation from nation. Education, station, sex, age, accidental associations, produce infinite shades of variety."

"It appears to us that all the works which indicate that an act is a proper subject for legal punishment meet in the act of false pleading. That false pleading always does some harm is plain. Even when it is not followed up by false evidence, it always delays justice. That false pleading produces any compensating good to atone for this harm has never, so far as we know, been even alleged…. We have as yet spoken only of the direct injury produced to honest litigants by false pleading. But this injury appears to us to be only a part, and perhaps not the greatest part, of the evil engendered by the practice. If there be any place where truth ought to be held in peculiar honour, from which falsehood ought to be driven with peculiar severity, in which exaggerations which elsewhere would be applauded as the innocent sport of the fancy, or pardoned as the natural effect of excited passion, ought to be discouraged, that place is a Court of Justice. We object, therefore, to the use of legal fictions, even when the meaning of those fictions is generally understood, and we have done our best to exclude them from this code, but that a person should come before a Court, should tell that Court premeditated and circumstantial lies for the purpose of preventing or postponing the settlement of a just demand, and that by so doing he should incur no punishment whatever, seems to us to be a state of things to which nothing but habit could reconcile wise and honest men. Public opinion is vitiated by the vicious state of the laws. Men who in any other circumstances would shrink from falsehood have no scruple about setting up false pleas against just demands. There is one place, and only one, where deliberate untruths told with the intent to injure are not considered as discreditable, and that place is a Court of Justice. Thus the authority of the tribunals operates to lower the standard of morality, and to diminish the esteem in which veracity is held; and the very place which ought to be kept sacred from misrepresentations such as would elsewhere be venial becomes the only place where it is considered as idle scrupulosity to shrink from deliberate falsehood."

"Intoxicated with animosity."

"It is altogether impossible to reason from the opinions which a man professes to his feelings and his actions; and in fact no person is ever such a fool as to reason thus, except when he wants a pretext for persecuting his neighbours. A Christian is commanded, under the strongest sanctions, to be just in all his dealings. Yet to how many of the twenty-four millions of professing Christians in these islands would any man in his senses lend a thousand pounds without security? A man who should act, for one day, on the supposition that all the people about him were influenced by the religion which they professed, would find himself ruined before night; and no man ever does act on that supposition in any of the ordinary concerns of life, in borrowing, in lending, in buying, or in selling. But when any of our fellow-creatures are to be oppressed, the case is different. Then we represent those motives which we know to be so feeble for good as omnipotent for evil. Then we lay to the charge of our victims all the vices and follies to which their doctrines, however remotely, seem to tend. We forget that the same weakness, the same laxity, the same disposition to prefer the present to the future, which make men worse than a good religion, make them better than a bad one."

"It is an uncontrolled truth, says Swift, that no man ever made an ill figure who understood his own talents, nor a good one who mistook them. Every day brings with it fresh illustrations of this weighty saying; but the best commentary that we remember is the history of Samuel Crisp. Men like him have their proper place, and it is a most important one, in the Commonwealth of Letters. It is by the judgment of such men that the rank of authors is finally determined. It is neither to the multitude, nor to the few who are gifted with great creative genius, that we are to look for sound critical decisions. The multitude, unacquainted with the best models, are captivated by whatever stuns and dazzles them. They deserted Mrs. Siddons to run after Master Betty; and they prefer, we have no doubt, Jack Sheppard to Van Artevelde. A man of great original genius, on the other hand, a man who has attained to mastery in some high walk of art, is by no means to be implicitly trusted as a judge of the performance of others. The erroneous decisions pronounced by such men are without number. It is commonly supposed that jealousy makes them unjust. But a more creditable explanation may easily be found. The very excellence of a work shows that some of the faculties of the author have been developed at the expense of the rest; for it is not given to the human intellect to expand itself widely in all directions at once, and to be at the same time gigantic and well proportioned. Whoever becomes pre-eminent in any art, nay, in any style of art, generally does so by devoting himself with intense and exclusive enthusiasm to the pursuit of one kind of excellence. His perception of other kinds of excellence is therefore too often impaired. Out of his own department he praises and blames at random; and is far less to be trusted than the mere connoisseur, who produces nothing, and whose business is only to judge and enjoy. One painter is distinguished by his exquisite finishing. He toils day after day to bring the veins of a cabbage-leaf, the folds of a lace veil, the wrinkles of an old woman’s face, nearer and nearer to perfection. In the time which he employs on a square foot of canvas, a master of a different order covers the walls of a palace with gods burying giants under mountains, or makes the cupola of a church alive with seraphim and martyrs. The more fervent the passion of each of these artists for his art, the higher the merit of each in his own line, the more unlikely it is that they will justly appreciate each other. Many persons who never handled a pencil probably do far more justice to Michael Angelo than would have been done by Gerard Douw, and far more justice to Gerard Douw than would have been done by Michael Angelo. It is the same with literature. Thousands who have no spark of the genius of Dryden or Wordsworth do to Dryden the justice which has never been done by Wordsworth, and to Wordsworth the justice which, we suspect, would never have been done by Dryden. Gray, Johnson, Richardson, Fielding, are all highly esteemed by the great body of intelligent and well-informed men. But Gray could see no merit in Rasselas; and Johnson could see no merit in the Bard. Fielding thought Richardson a solemn prig; and Richardson perpetually expressed contempt and disgust for Fielding’s lowness."

"It has often been found that profuse expenditures, heavy taxation, absurd commercial restrictions, corrupt tribunals, disastrous wars, seditions, persecutions, conflagrations, inundation, have not been able to destroy capital so fast as the exertions of private citizens have been able to create it."

"It is clear that those vices which destroy domestic happiness ought to be as much as possible repressed. It is equally clear that they cannot be repressed by penal legislation. It is therefore right and desirable that public opinion should be directed against them. But it should be directed against them uniformly, steadily, and temperately, not by sudden fits and starts. There should be one weight and one measure. Decimation is always an objectionable mode of punishment. It is the resource of judges too indolent and hasty to investigate facts and to discriminate nicely between shades of guilt. It is an irrational practice, even when adopted by military tribunals. When adopted by the tribunal of public opinion, it is infinitely more irrational. It is good that a certain portion of disgrace should constantly attend on certain bad actions. But it is not good that the offenders should merely have to stand the risks of a lottery of infamy, that ninety-nine out of every hundred should escape, and that the hundredth, perhaps the most innocent of the hundred, should pay for all."

"It is dangerous to select where there is so much that deserves the highest praise. We will venture, however, to say that any person who wishes to form a just notion of the extent and variety of Addison’s powers will do well to read at one sitting the following papers: the two Visits to the Abbey, the Visit to the Exchange, the Journal of the Retired Citizen, the Vision of Mirza, the Transmigrations of Pug the Monkey, and the Death of Sir Roger de Coverley."

"It is curious to observe how differently these great men estimated the value of every kind of knowledge. Take Arithmetic for example. Plato, after speaking slightly of the convenience of being able to reckon and compute in the ordinary transactions of life, passes to what he considers as a far more important advantage. The study of the properties of numbers, he tells us, habituates the mind to the contemplation of pure truth, and raises us above the material universe. He would have his disciples apply themselves to this study, not that they may be able to buy or sell, not that they may qualify themselves to be shopkeepers or travelling merchants, but that they may learn to withdraw their minds from the ever-shifting spectacle of this visible and tangible world, and to fix them on the immutable essences of things. [Plato’s Republic, Book 7.] Bacon, on the other hand, valued this branch of knowledge only on account of its uses with reference to that visible and tangible world which Plato so much despised. He speaks with scorn of the mystical arithmetic of the later Platonists, and laments the propensity of mankind to employ on matters of mere curiosity powers the whole exertion of which is required for purposes of solid advantage. He advises arithmeticians to leave these trifles, and to employ themselves in framing convenient expressions which may be of use in physical researches. [De Augmentis, Lib. 3, Cap. 6.] The same reasons which led Plato to recommend the study of Arithmetic led him to recommend also the study of mathematics. The vulgar crowd of geometricians, he says, will not understand him. They have practice always in view. They do not know that the real use of the science is to lead men to the knowledge of abstract, essential, eternal truth. [Plato’s Republic, Book 7.] Indeed, if we are to believe Plutarch, Plato carried this feeling so far that he considered geometry as degraded by being applied to any purpose of vulgar utility. Archytas, it seems, had framed machines of extraordinary power on mathematical principles. [Plutarch, Sympos., viii., and Life of Marcellus. The machines of Archytas are also mentioned by Aulus Gellius and Diogenes Laertius.] Plato remonstrated with his friend, and declared that this was to degrade a noble intellectual exercise into a low craft, fit only for carpenters and wheelwrights. The office of geometry, he said, was to discipline the mind, not to minister to the base wants of the body. His interference was successful; and from that time, according to Plutarch, the science of mechanics was considered as unworthy of the attention of a philosopher. Archimedes in a later age imitated and surpassed Archytas. But even Archimedes was not free from the prevailing notion that geometry was degraded by being employed to produce anything useful. It was with difficulty that he was induced to stoop from speculation to practice. He was half ashamed of those inventions which were the wonder of hostile nations, and always spoke of them slightingly as mere amusements, as trifles in which a mathematician might be suffered to relax his mind after intense application to the higher parts of his science."

"It is better that men should be governed by priestcraft than violence."

"It is easy to perceive from the scanty remains of his oratory that the same compactness of expression and richness of fancy which appear in his writings characterized his speeches; and that his extensive acquaintance with literature and history enabled him to entertain his audience with a vast variety of illustrations and illusions which were generally happy and apposite, but which were probably not least pleasing to the taste of that age when they were such as would now be thought childish or pedantic. It is evident also that he was, as indeed might have been expected, perfectly free from those faults which are generally found in an advocate who, after having risen to eminence at the bar, enters the House of Commons; that it was his habit to deal with every great question, not in small detached portions, but as a whole; that he refined little, and that his reasonings were those of a capacious rather than a subtle mind. Ben Jonson, a most unexceptionable judge, has described Bacon’s eloquence in words, which, though often quoted, will bear to be quoted again. There happened in my time one noble speaker who was full of gravity in his speaking. His language, where he could spare or pass by a jest, was nobly censorious. No man ever spoke more neatly, more pressly, more weighty, or suffered less emptiness, less idleness, in what he uttered. No member of his speech but consisted of his own graces. His hearers could not cough or look aside from him without loss. He commanded where he spoke, and had his judges angry and pleased at his devotion. No man had their affections more in his power. The fear of every man that heard him was lest he should make an end. From the mention which is made of judges, it would seem that Jonson had heard Bacon only at the Bar. Indeed, we imagine that the House of Commons was then almost inaccessible to strangers. It is not probable that a man of Bacon’s nice observation would speak in Parliament exactly as he spoke in the Court of Queen’s Bench. But the graces of manner and language must, to a great extent, have been common between the Queen’s Counsel and the Knight of the Shire."

"It is good to be often reminded of the inconsistency of human nature, and to learn to look without wonder or disgust on the weaknesses which are found in the strongest minds."

"It is evident that a portrait-painter who was able only to represent faces and figures such as those which we pay money to see at fairs would not, however spirited his execution might be, take rank among the highest artists. He must always be placed below those who have skill to seize peculiarities which do not amount to deformity. The slighter those peculiarities, the greater is the merit of the limner who can catch them and transfer them to his canvas. To paint Daniel Lambert or the living skeleton, the pig-faced lady or the Siamese twins, so that nobody can mistake them, is an exploit within the reach of a sign-painter. A third-rate artist might give us the squint of Wilkes, and the depressed nose and protuberant cheeks of Gibbon. It would require a much higher degree of skill to paint two such men as Mr. Canning and Sir Thomas Lawrence, so that nobody who had ever seen them could for a moment hesitate to assign each picture to its original. Here the mere caricaturist would be quite at fault. He would find in neither face anything on which he could lay hold for the purpose of making a distinction. Two ample bald foreheads, two regular profiles, two full faces of the same oval form, would baffle his art; and he would be reduced to the miserable shift of writing their names at the foot of his picture. Yet there was a great difference; and a person who had seen them once would no more have mistaken one of them for the other than he would have mistaken Mr. Pitt for Mr. Fox. But the difference lay in delicate lineaments and shades, reserved for pencils of a rare order."

"It is evident, then, that those who are afraid of superficial knowledge do not mean by superficial knowledge knowledge which is superficial when compared with the whole quantity of truth capable of being known. For in that sense all human knowledge is, and always has been, and always will be, superficial. What, then, is the standard? Is it the same two years together in any country? Is it the same at the same moment in any two countries? Is it not notorious that the profundity of one age is the shallowness of the next? that the profundity of one nation is the shallowness of a neighbouring nation? Ramohun Roy passed among Hindoos for a man of profound Western learning; but he would have been but a very superficial member of this Institute. Strabo was justly entitled to be called a profound geographer eighteen hundred years ago. But a teacher of geography who had never heard of America would now be laughed at by the girls of a boarding-school. What would now be thought of the greatest chemist of 1746, or of the greatest geologist of 1746? The truth is that in all experimental science mankind is, of necessity, constantly advancing. Every generation, of course, has its front rank and its rear rank; but the rear rank of a later generation occupies the ground which was occupied by the front rank of a former generation."

"It is evidently on the real distribution of power, and not on names and badges, that the happiness of nations must depend. The representative system, though doubtless a great and precious discovery in politics, is only one of the many modes in which the democratic part of the community can efficiently check the governing few. That certain men have been chosen as deputies of the people,—that there is a piece of paper stating such deputies to possess certain powers,—these circumstances in themselves constitute no security for good government. Such a constitution nominally existed in France; while, in fact, an oligarchy of committees and clubs trampled at once on the electors and the elected. Representation is a very happy contrivance for enabling large bodies of men to exert their power with less risk of disorder than there would otherwise be. But, assuredly, it does not of itself give power. Unless a representative assembly is sure of being supported in the last resort by the physical strength of large masses who have spirit to defend the constitution and sense to defend it in concert, the mob of the town in which it meets may overawe it; the howls of the listeners in its gallery may silence its deliberations; an able and daring individual may dissolve it. And if that sense and that spirit of which we speak be diffused through a society, then, even without a representative assembly, that society will enjoy many of the blessings of good government."

"It is impossible for us, with our limited means, to attempt to educate the body of the people. We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect. To that class we may leave it to refine the vernacular dialects of the country, to enrich those dialects with terms of science borrowed from the Western nomenclature, and to render them by degrees fit vehicles for conveying knowledge to the great mass of the population."

"It is impossible to deny that the polity of the Church of Rome is the very master-piece of human wisdom. In truth, nothing but such a polity could, against such assaults, have borne up such doctrines. The experience of twelve hundred eventful years, the ingenuity and patient care of forty generations of statesmen, have improved that polity to such perfection, that, among the contrivances which have been devised for deceiving and controlling mankind, it occupies the highest place."

"It is in the tragi-comedies that these absurdities strike us most. The two races of men, or rather the angels and the baboons, are there presented to us together. We meet in one scene with nothing but gross, selfish, unblushing, lying libertines of both sexes, who, as a punishment, we suppose, for their depravity, are condemned to talk nothing but prose. But, as soon as we meet with people who speak in verse, we know that we are in society which would have enraptured the Cathos and Madelon of Molière, in society for which Oroondates would have too little of the lover, and Clelia too much of the coquette."

"It is impossible to deny, however, that Walpole’s writings have real merit, and merit of a very rare, though not of a very high, kind. Sir Joshua Reynolds used to say that, though nobody would for a moment compare Claude to Raphael, there would be another Raphael before there was another Claude. And we own that we expect to see fresh Humes and fresh Burkes before we again fall in with that peculiar combination of moral and intellectual qualities to which the writings of Walpole owe their extraordinary popularity."

"It is indeed amusing to turn over some late volumes of periodical works, and to see how many immortal productions have, within a few months, been gathered to the Poems of Blackmore and the novels of Mrs. Behn; how many profound views of human nature, and exquisite delineations of fashionable manners, and vernal, and sunny, and refreshing thoughts, and high imaginings, and young breathings, and embodyings, and pinings, and minglings with the beauty of the universe, and harmonies which dissolve the soul in a passionate sense of loveliness and divinity, the world has contrived to forget. The names of the books and of the writers are buried in as deep an oblivion as the name of the builder of Stonehenge. Some of the well-puffed fashionable novels of eighteen hundred and twenty-nine hold the pastry of eighteen hundred and thirty; and others, which are now extolled in language almost too high-flown for the merits of Don Quixote, will, we have no doubt, line the trunks of eighteen hundred and thirty-one. But, though we have no apprehensions that puffing will ever confer permanent reputation on the undeserving, we still think its influence most pernicious. Men of real merit will, if they persevere, at last reach the station, to which they are entitled, and intruders will be ejected with contempt and derision. But it is no small evil that the avenues to fame should be blocked up by a swarm of noisy, pushing, elbowing pretenders, who, though they will not ultimately be able to make good their own entrance, hinder, in the mean time, those who have a right to enter. All who will not disgrace themselves by joining in the unseemly scuffle must expect to be at first hustled and shouldered back. Some men of talents, accordingly, turn away in dejection from pursuits in which success appears to bear no proportion to desert. Others employ in self-defense the means by which competitors, far inferior to themselves, appear for a time to obtain a decided advantage. There are few who have sufficient confidence in their own powers and sufficient elevation of mind to wait with secure and contemptuous patience, while dunce after dunce presses before them. Those who will not stoop to the baseness of the modern fashion are too often discouraged. Those who do stoop to it are always degraded."