Great Throughts Treasury

This site is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Alan William Smolowe who gave birth to the creation of this database.

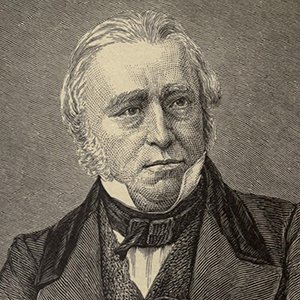

Thomas Macaulay, fully Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay

British Poet,Historian, Essayist, Biographer, Secretary of War, Paymaster-General and Whig Politician

"Some people may think the object of the Baconian philosophy a low object, but they cannot deny that, high or low, it has been attained. They cannot deny that every year makes an addition to what Bacon called fruit. They cannot deny that mankind have made, and are making, great and constant progress in the road which he pointed out to them. Was there any such progressive movement among the ancient philosophers? After they had been declaiming eight hundred years, had they made the world better than when they began? Our belief is that, among the philosophers themselves, instead of a progressive improvement there was a progressive degeneracy. An abject superstition which Democritus or Anaxagoras would have rejected with scorn added the last disgrace to the long dotage of the Stoic and Platonic schools. Those unsuccessful attempts to articulate which are so delightful and interesting in a child shock and disgust us in an aged paralytic; and, in the same way, those wild mythological fictions which charm us when we hear them lisped by Greek poetry in its infancy excite a mixed sensation of pity and loathing when mumbled by Greek philosophy in its old age."

"Some weak men had imagined that religion and morality stood in need of the protection of the licenser. The event signally proved that they were in error. In truth, the censorship had scarcely put any restraint on licentiousness or profaneness. The Paradise Lost had narrowly escaped mutilation: for the Paradise Lost was the work of a man whose politics were hateful to the government. But Etherege’s She Would If She Could, Wycherley’s Country Wife, Dryden’s Translations from the Fourth Book of Lucretius, obtained the Imprimatur without difficulty: for Etherege, Wycherley, and Dryden were courtiers. From the day on which the emancipation of our literature was accomplished, the purification of our literature began. That purification was effected, not by the intervention of senates or magistrates, but by the opinion of the great body of educated Englishmen, before whom good and evil were set, and who were left free to make their choice. During a hundred and sixty years the liberty of our press has been constantly becoming more and more entire; and during those hundred and sixty years the restraint imposed on writers by the general feeling of readers has been constantly becoming more and more strict. At length even that class of works in which it was formerly thought that a voluptuous imagination was privileged to disport itself, love songs, comedies, novels, have become more decorous than the sermons of the seventeenth century. At this day foreigners, who dare not print a word reflecting on the government under which they live, are at a loss to understand how it happens that the freest press in Europe is the most prudish."

"Some years before his death, Dryden altogether ceased to write for the stage. He had turned his powers in a new direction, with success the most splendid and decisive. His taste had gradually awakened his creative faculties. The first rank in poetry was beyond his reach; but he challenged and secured the most honourable place in the second. His imagination resembled the wings of an ostrich: it enabled him to run, though not to soar. When he attempted the highest flights, he became ridiculous; but while he remained in a lower region, he outstripped all competitors."

"Somers spoke last [in the Trial of the Seven Bishops]. He spoke little more than five minutes: but every word was full of weighty matter; and when he sat down, his reputation as an orator and a constitutional lawyer was established."

"Such are the opposite errors which men commit when their morality is not a science but a taste, when they abandon eternal principles for accidental associations. We have illustrated our meaning by an instance taken from history. We will select another from fiction. Othello murders his wife; he gives orders for the murder of his lieutenant; he ends by murdering himself. Yet he never loses the esteem and affection of Northern readers. His intrepid and ardent spirit redeems everything. The unsuspecting confidence with which he listens to his adviser, the agony with which he shrinks from the thought of shame, the tempest of passion with which he commits his crimes, and the haughty fearlessness with which he avows them, give an extraordinary interest to his character. Iago, on the contrary, is the object of universal loathing. Many are inclined to suspect that Shakespeare has been seduced into an exaggeration unusual with him, and has drawn a monster who has no archetype in human nature. Now we suspect that an Italian audience in the fifteenth century would have felt very differently. Othello would have inspired nothing but detestation and contempt. The folly with which he trusts the friendly professions of a man whose promotion he had obstructed, the credulity with which he takes unsupported assertions, and trivial circumstances, for unanswerable proofs, the violence with which he silences the exculpation till the exculpation can only aggravate his misery, would have excited the abhorrence and disgust of the spectators. The conduct of Iago they would assuredly have condemned; but they would have condemned it as we condemn that of his victim. Something of interest and respect would have mingled with their disapprobation. The readiness of the traitor’s wit, the clearness of his judgment, the skill with which he penetrates the dispositions of others and conceals his own, would have insured to him a certain portion of their esteem."

"Such, or nearly such, was the change which passed on the Mogul empire during the forty years which followed the death of Aurungzebe. A succession of nominal sovereigns, sunk in indolence and debauchery, sauntered away life in secluded palaces, chewing bang, fondling concubines, and listening to buffoons. A succession of ferocious invaders descended through the western passes to prey on the defenseless wealth of Hindostan. A Roman conqueror crossed the Indus, marched through the gales of Delhi, and bore away in triumph those treasures of which the magnificence had astounded Roe and Bernier, the Peacock Throne, on which the richest jewels of Golconda had been disposed by the most skilful hands of Europe, and the inestimable Mountain of Light, which, after many strange vicissitudes, lately shone in the bracelet of Runjeet Sing, and is now destined to adorn the hideous idol of Orissa. The Afghan soon followed to complete the work of devastation which the Persian had begun. The warlike tribes of Rajpootana threw off the Mussulman yoke. A band of mercenary soldiers occupied Rohilcund. The Seiks ruled on the Indus. The Jauts spread dismay along the Jumna. The highlands which border on the western sea-coast of India poured forth a yet more formidable race, a race which was long the terror of every native power, and which, after many desperate and doubtful struggles, yielded only to the fortune and genius of England. It was under the reign of Aurungzebe that this wild clan of plunderers first descended from their mountains; and soon after his death every corner of his wide empire learned to tremble at the mighty name of the Mahrattas. Many fertile vice-royalties were entirely subdued by them. Their dominions stretched across the peninsula from sea to sea. Mahratta captains reigned at Poonah, at Gualior, in Guzerat, in Berar, and in Tanjore. Nor did they though they had become great sovereigns therefore cease to be freebooters. They still retained the predatory habits of their forefathers. Every region which was not subject to their rule was wasted by their incursions. Wherever their kettle-drums were heard, the peasant threw his bag of rice on his shoulder, hid his small savings in his girdle, and fled with his wife and children to the mountains or the jungles, to the milder neighbourhood of the hyæna and the tiger. Many provinces redeemed their harvests by the payment of an annual ransom."

"Suppose that Justinian, when he closed the schools of Athens, had called on the last few sages who still haunted the Portico, and lingered round the ancient plane-trees, to show their title to public veneration: suppose that he had said, A thousand years have elapsed since, in this famous city, Socrates posed Protagoras and Hippias; during those thousand years a large proportion of the ablest men of every generation has been employed in constant efforts to bring to perfection the philosophy which you teach; that philosophy has been munificently patronized by the powerful; its professors have been held in the highest esteem by the public; it has drawn to itself almost all the sap and vigour of the human intellect: and what has it effected? What profitable truth has it taught us which we should not equally have known without it? What has it enabled us to do which we should not have been equally able to do without it? Such questions, we suspect, would have puzzled Simplicius and Isidore. Ask a follower of Bacon what the new philosophy, as it was called in the time of Charles the Second, has effected for mankind, and his answer is ready: It has lengthened life; it has mitigated pain; it has extinguished diseases; it has increased the fertility of the soil; it has given new securities to the mariner; it has furnished new arms to the warrior; it has spanned great rivers and estuaries with bridges of form unknown to our fathers; it has guided the thunder-bolt innocuously from heaven to earth; it has lighted up the night with the splendour of the day; it has extended the range of the human vision; it has multiplied the power of the human muscles; it has accelerated motion; it has annihilated distance; it has facilitated intercourse, correspondence, all friendly offices, all dispatch of business; it has enabled man to descend to the depths of the sea, to soar into the air, to penetrate securely into the noxious recesses of the earth, to traverse the land in cars which whirl along without horses, and the ocean in ships which run ten knots an hour against the wind. These are but a part of its fruits, and of its first fruits. For it is a philosophy which never rests, which has never attained, which is never perfect. Its law is progress. A point which yesterday was invisible is its goal to-day, and will be its starting-post to-morrow."

"Such a military force as this was a far stronger restraint on the regal power than any legislative assembly. The army, now the most formidable instrument of the executive power, was then the most formidable check on that power. Resistance to an established government, in modern times so difficult and perilous an enterprise, was in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries the simplest and easiest matter in the world. Indeed, it was far too simple and easy. An insurrection was got up then almost as easily as a petition is got up now. In a popular cause, or even in an unpopular cause favoured by a few great nobles, a force of ten thousand armed men was raised in a week."

"Such night in England ne'er had been, nor ne'er again shall be."

"Surely, said Mr. Milton, and that I may end this long debate with words in which we shall both agree, I hold that, as freedom is the only safeguard of governments, so are order and moderation generally necessary to preserve freedom. Even the vainest opinions of men are not to be outraged by those who propose to themselves the happiness of men for their end, and who must work with the passions of men for their means. The blind reverence for things ancient is indeed so foolish that it might make a wise man laugh, if it were not also sometimes so mischievous that it would rather make a good man weep. Yet, since it may not be wholly cured, it must be discreetly indulged; and therefore those who would amend evil laws should consider rather how much it may be safe to spare, than how much it may be possible to change. Have you not heard that men who have been shut up for many years in dungeons shrink if they see the light, and fall down if their irons be struck off? And so, when nations have long been in the house of bondage, the chains which have crippled them are necessary to support them, the darkness which hath weakened their sight is necessary to preserve it. Therefore release them not too rashly, lest they curse their freedom and pine for their prison."

"Surely this is a hard saying. Before we admit that the Emperor Julian in employing the influence and the funds at his disposal for the extinction of Christianity was doing no more than his duty, before we admit that the Arian Theodoric would have committed a crime if he had suffered a single believer in the divinity of Christ to hold any civil employment in Italy, before we admit that the Dutch government is bound to exclude from office all members of the Church of England, the King of Bavaria to exclude from office all Protestants, the Great Turk to exclude from office all Christians, the King of Ava to exclude from office all who hold the unity of God, we think ourselves entitled to demand very full and accurate demonstration. When the consequences of a doctrine are so startling we may well require that its foundations shall be very solid."

"Temple was a man of the world amongst men of letters, a man of letters amongst men of the world."

"Take chemistry. Our philosopher of the thirteenth century shall be, if you please, an universal genius, chemist as well as astronomer. He has perhaps got so far as to know that if he mixes charcoal and saltpetre in certain proportions and then applies fire there will be an explosion which will shatter all his retorts and aludels; and he is proud of knowing what will in a later age be familiar to all the idle boys in the kingdom. But there are departments of science in which he need not fear the rivalry of Black, Lavoisier, or Cavendish, or Davy. He is in hot pursuit of the philosopher’s stone, of the stone that is to bestow wealth, and health, and longevity. He has a long array of strangely shaped vessels, filled with white and red oil constantly boiling. The moment of projection is at hand; and soon all his kettles and gridirons will be turned into pure gold. Poor Professor Faraday can do nothing of the sort. I should deceive you if I held out to you the smallest hope that he will ever turn your half-pence into sovereigns. But if you can induce him to give at our Institute a course of lectures such as I once heard him give to the Royal Institution to children in the Christmas holidays, I can promise you that you will know more about the effects produced on bodies by heat and moisture than was known to some alchemists who in the middle ages were thought worthy of the patronage of Kings."

"Surely no Christian can deny that every human being has a right to be allowed every gratification which produces no harm to others, and to be spared every mortification which produces no good to others. Is it not a source of mortification to a class of men that they are excluded from political power? If it be, they have, on Christian principles, a right to be freed from that mortification, unless it can be shown that their exclusion is necessary for the averting of some greater evil. The presumption is evidently in favour of toleration. It is for the prosecutor to make out his case."

"That a historian should not record trifles, that he should confine himself to what is important, is perfectly true. But many writers seem never to have considered on what the historical importance of an event depends. They seem not to be aware that the importance of a fact when that fact is considered with reference to its immediate effects, and the importance of the same fact when that fact is considered as part of the materials for the construction of a science, are two very different things. The quantity of good or evil which a transaction produces is by no means necessarily proportioned to the quantity of light which that transaction affords as to the way in which good or evil may hereafter be produced. The poisoning of an emperor is in one sense a far more serious matter than the poisoning of a rat. But the poisoning of a rat may be an era in chemistry; and an emperor may be poisoned by such ordinary means, and with such ordinary symptoms, that no scientific journal would notice the occurrence. An action for a hundred thousand pounds is in one sense a more momentous affair than an action for fifty pounds. But it by no means follows that the learned gentlemen who report the proceedings of the courts of law ought to give a fuller account of an action for a hundred thousand pounds than of an action for fifty pounds. For a cause in which a large sum is at stake may be important only to the particular plaintiff and the particular defendant. A cause, on the other hand, in which a small sum is at stake may establish some great principle interesting to half the families in the kingdom. The case is exactly the same with that class of subjects of which historians treat."

"That advice so pernicious will not be followed, I am well assured; yet I cannot but listen to it with uneasiness. I cannot but wonder that it should proceed from the lips of men who are constantly lecturing us on the duty of consulting history and experience. Have they never heard what effects counsels like their own, when too faithfully followed, have produced? Have they never visited that neighbouring country which still presents to the eye, even of a passing stranger, the signs of a great dissolution and renovation of society? Have they never walked by those stately mansions, now sinking into decay and portioned out into lodging-rooms, which line the silent streets of the Faubourg St. Germain? Have they never seen the ruins of those castles whose terraces and gardens overhang the Loire? Have they never heard that from those magnificent hotels, from those ancient castles, an aristocracy as splendid, as brave, as proud, as accomplished, as ever Europe saw, was driven forth to exile and beggary, to implore the charity of hostile governments and hostile creeds, to cut wood in the back settlements of America, or to teach French in the school-rooms of London? And why were those haughty nobles destroyed with that utter destruction? Why were they scattered over the face of the earth, their titles abolished, their escutcheons defaced, their parks wasted, their palaces dismantled, their heritage given to strangers? Because they had no sympathy with the people, no discernment of the signs of their time; because, in the pride and narrowness of their hearts, they called those whose warnings might have saved them theorists and speculators; because they refused all concession till the time had arrived when no concession would avail."

"That critical discernment is not sufficient to make men poets, is generally allowed. Why it should keep them from becoming poets is not, perhaps, equally evident; but the fact is, that poetry requires not an examining but a believing frame of mind. Those feel it most, and write it best, who forget that it is a work of art; to whom its imitations, like the realities from which they are taken, are subjects, not for connoisseurship, but for tears and laughter, resentment and affection; who are too much under the influence of the illusion to admire the genius which has produced it; who are too much frightened for Ulysses in the cave of Polyphemus to care whether the pun about Outis be good or bad; who forget that such a person as Shakespeare ever existed, while they weep and curse with Lear. It is by giving faith to the creations of the imagination that a man becomes a poet. It is by treating those creations as deceptions, and by resolving them, as nearly as possible, into their elements, that he becomes a critic. In the moment in which the skill of the artist is perceived, the spell of the art is broken. These considerations account for the absurdities into which the greatest writers have fallen when they have attempted to give general rules for composition, or to pronounce judgment on the works of others. They are accustomed to analyze what they feel; they therefore perpetually refer their emotions to causes which have not in the slightest degree tended to produce them. They feel pleasure in reading a book. They never consider that this pleasure may be the effect of ideas which some unmeaning expression, striking on the first link of a chain of associations, may have called up in their own minds,—that they have themselves furnished to the author the beauties which they admire."

"That is the best government which desires to make the people happy and knows how to make them happy. Neither the inclination nor the knowledge will suffice alone; and it is difficult to find them together."

"That history would be more amusing if this etiquette were relaxed will, we suppose, be acknowledged. But would it be less dignified or less useful? What do we mean when we say that one past event is important and another insignificant? No past event has any intrinsic importance. The knowledge of it is valuable only as it leads us to form just calculations with respect to the future. A history which does not serve this purpose, though it may be filled with battles, treaties, and commotions, is as useless as the series of turnpike-tickets collected by Sir Matthew Mite."

"That leader at length arose. The philosophy which he taught was essentially new. It differed from that of the celebrated ancient teachers, not merely in method, but also in object. Its object was the good of mankind, in the sense in which the mass of mankind always have understood and always will understand the word good. Meditor, said Bacon, instaurationem philosophiæ ejusmodi quæ nihil inanis aut abstracti habeat, quæque vitæ humanæ conditiones in melius provehat. [Redargutio Philosophiarum.]"

"That which was eminently his own in his [Bacon’s] system was the end which he proposed to himself. The end being given, the means, as it appears to us, could not well be mistaken. If others had aimed at the same object with Bacon, we hold it to be certain that they would have employed the same method with Bacon. It would have been hard to convince Seneca that the inventing of a safety-lamp was an employment worthy of a philosopher. It would have been hard to persuade Thomas Aquinas to descend from the making of syllogisms to the making of gunpowder. But Seneca would never have doubted for a moment that it was only by means of a series of experiments that a safety-lamp could he invented. Thomas Aquinas would never have thought that his barbara and baralipton would enable him to ascertain the proportion which charcoal ought to bear to saltpetre in a pound of gunpowder. Neither common sense nor Aristotle would have suffered him to fall into such an absurdity. By stimulating men to the discovery of new truth, Bacon stimulated them to employ the inductive method, the only method, even the ancient philosophers and the schoolmen themselves being judges, by which new truth can be discovered. By stimulating men to the discovery of useful truth he furnished them with a motive to perform the inductive process well and carefully. His predecessors had been, in his phrase, not interpreters, but anticipators, of nature. They had been content with the first principles at which they had arrived by the most scanty and slovenly induction. And why was this? It was, we conceive, because their philosophy proposed to itself no practical end, because it was merely in exercise of the mind…. What Bacon did for inductive philosophy may, we think, be fairly stated thus: The objects of preceding speculators were objects which could be attained without careful induction. Those speculators, therefore, did not perform the inductive process carefully. Bacon stirred up men to pursue an object which could be attained only by induction, and by induction carefully performed; and consequently induction was more carefully performed. We do not think that the importance of what Bacon did for inductive philosophy has ever been over-rated. But we think that the nature of his services is often mistaken, and was not fully understood even by himself. It was not by furnishing philosophers with rules for performing the inductive process well, but by furnishing them with a motive for performing it well, that he conferred so vast a benefit on society. To give to the human mind a direction which it shall retain for ages is the rare prerogative of a few imperial spirits. It cannot, therefore, be uninteresting to inquire what was the moral and intellectual constitution which enabled Bacon to exercise so vast an influence on the world."

"That the sacerdotal order should encroach on the functions of the civil government would, in our time, be a great evil. But that which in an age of good government is an evil may, in an age of grossly bad government, be a blessing. It is better that mankind should be governed by wise laws well administered, and by an enlightened public opinion, than by brute violence, by such a prelate as Dunstan than by such a warrior as Penda. A society sunk in ignorance, and ruled by mere physical force, has great reason to rejoice when a class of which the influence is intellectual and moral rises to ascendency. Such a class will doubtless abuse its power: but mental power, even when abused, is still a nobler and better power than that which consists merely in corporeal strength. We read in our Saxon chronicles of tyrants who, when at the height of greatness, were smitten by remorse, who abhorred the pleasures and dignities which they had purchased by guilt, who abdicated their crowns, and who sought to atone for their offences by cruel penances and incessant prayers. These stories have drawn forth bitter expressions of contempt from some writers, who, while they boasted of liberality, were in truth as narrow-minded as any monk of the dark ages, and whose habit was to apply to all events in the history of the world the standard received in the Parisian society of the eighteenth century. Yet surely a system which, however deformed by superstition, introduced strong moral restraints into communities previously governed only by vigour of muscle and by audacity of spirit, a system which taught the fiercest and mightiest ruler that he was, like his meanest bondman, a responsible being, might have seemed to deserve a more respectful mention from philosophers and philanthropists."

"That perfect disinterestedness and self-devotion of which man seems incapable, but which is sometimes found in woman."

"The advice and medicine which the poorest labourer can now obtain, in disease or after an accident, is far superior to what Henry the Eighth could have commanded. Scarcely any part of the country is out of the reach of practitioners who are probably not so far inferior to Sir Henry Halford as they are superior to Dr. Butts. That there has been a great improvement in this respect Mr. Southey allows. Indeed, he could not well have denied it. But, says he, the evils for which these sciences are the palliative have increased since the time of the Druids, in a proportion that heavily overweighs the benefit of improved therapeutics. We know nothing either of the diseases or the remedies of the Druids. But we are quite sure that the improvement of medicine has far more than kept pace with the increase of disease during the last three centuries. This is proved by the best possible evidence. The term of human life is decidedly longer in England than in any former age respecting which we possess any information on which we can rely. All the rants in the world about picturesque cottages and temples of Mammon will not shake this argument! No test of the physical well-being of society can be named so decisive as that which is furnished by bills of mortality. That the lives of the people of this country have been gradually lengthening during the course of several generations, is as certain as any fact in statistics; and that the lives of men should become longer and longer, while their bodily condition during life is becoming worse and worse, is utterly incredible."

"That, on great emergencies, the State may justifiably pass a retrospective act against an offender, we have no doubt whatever. We are acquainted with only one argument on the other side which has in it enough of reason to bear an answer. Warning, it is said, is the end of punishment. But a punishment inflicted, not by a general rule, but by an arbitrary discretion, cannot serve the purpose of a warning. It is therefore useless; and useless pain ought not to be inflicted. This sophism has found its way into several books on penal legislation. It admits, however, of a very simple refutation. In the first place, punishments ex post facto are not altogether useless even as warnings. They are warnings to a particular class which stand in great need of warnings, to favourites and ministers. They remind persons of this description that there may be a day of reckoning for those who ruin and enslave their country in all the forms of law. But this is not all. Warning is, in ordinary cases, the principal end of punishment; but it is not the only end. To remove the offender, to preserve society from those dangers which are to be apprehended from his incorrigible depravity, is often one of the ends. In the case of such a knave as Wild, or such a ruffian as Thurtell, it is a very important end. In the case of a powerful and wicked statesman, it is infinitely more important; so important as alone to justify the utmost severity, even though it were certain that his fate would not deter others from imitating his example. At present, indeed, we should think it extremely pernicious to take such a course, even with a worse minister than Strafford, if a worse could exist; for, at present, Parliament has only to withhold its support from a Cabinet to produce an immediate change of hands. The case was widely different in the reign of Charles the First. That Prince had governed during eleven years without any Parliament, and, even when Parliament was sitting, had supported Buckingham against its most violent remonstrances."

"The ages in which the masterpieces of imagination have been produced have by no means been those in which taste has been most correct. It seems that the creative faculty and the critical faculty cannot exist together in their highest perfection. The causes of this phenomenon it is not difficult to assign. It is true that the man who is best able to take a machine to pieces, and who most clearly comprehends the manner in which all its wheels and springs conduce to its general effect, will be the man most competent to form another machine of similar power. In all the branches of physical and moral science which admit of perfect analysis he who can resolve will be able to combine. But the analysis which criticism can effect of poetry is necessarily imperfect. One element must forever elude its researches; and that is the very element by which poetry is poetry. In the description of nature, for example, a judicious reader will easily detect an incongruous image. But he will find it impossible to explain in what consists the art of a writer who in a few words brings some spot before him so vividly that he shall know it as if he had lived there from childhood; while another, employing the same materials, the same verdure, and the same flowers, committing no inaccuracy, introducing nothing which can be positively pronounced superfluous, omitting nothing which can be positively pronounced necessary, shall produce no more effect than an advertisement of a capital residence and a desirable pleasure-ground."

"That wonderful book, while it obtains admiration from the most fastidious critics, is loved by those who are too simple to admire it."

"The ambition of Oliver was of no vulgar kind. He never seems to have coveted despotic power. He at first fought sincerely and manfully for the Parliament, and never deserted it till it had deserted its duty. If he dissolved it by force, it was not till he found that the few members who remained after so many deaths, secessions, and expulsions were desirous to appropriate to themselves a power which they held only in trust, and to inflict upon England the curse of a Venetian oligarchy. But even when thus placed by violence at the head of affairs, he did not assume unlimited power. He gave the country a constitution far more perfect than any which had at that time been known in the world. He reformed the representative system in a manner which has extorted praise even from Lord Clarendon. For himself he demanded indeed the first place in the commonwealth; but with powers scarcely so great as those of a Dutch stadtholder or an American president. He gave the Parliament a voice in the appointment of ministers, and left to it the whole legislative authority, not even reserving to himself a veto on its enactments; and he did not require that the chief magistracy should be hereditary in his family. Thus far, we think, if the circumstances of the time and the opportunities which he had of aggrandizing himself be fairly considered, he will not lose by comparison with Washington or Bolivar."

"The ambassador [of Russia] and the grandees who accompanied him were so gorgeous that all London crowded to stare at them, and so filthy that nobody dared to touch them. They came to the court balls dropping pearls and vermin."

"The ancient philosophers did not neglect natural science; but they did not cultivate it for the purpose of increasing the power and ameliorating the condition of man. The taint of barrenness had spread from ethical to physical speculations. Seneca wrote largely on natural philosophy, and magnified the importance of that study. But why? Not because it tended to assuage suffering, to multiply the conveniences of life, to extend the empire of man over the material world; but solely because it tended to raise the mind above low cares, to separate it from the body, to exercise its subtilty in the solution of very obscure questions. [Seneca, Nat. Quæst., præf., lib. 3.] Thus natural philosophy was considered in the light merely of a mental exercise. It was made subsidiary to the art of disputation; and it consequently proved altogether barren of useful discoveries."

"The ancient philosophy disdained to be useful, and was content to be stationary. It dealt largely in theories of moral perfection, which were so sublime that they never could be more than theories; in attempts to solve insoluble enigmas; in exhortations to the attainment of unattainable frames of mind. It could not condescend to the humble office of ministering to the comfort of human beings. All the schools contemned that office as degrading; some censured it as immoral. Once indeed Posidonius, a distinguished writer of the age of Cicero and Cæsar, so far forgot himself as to enumerate among the humble blessings which mankind owed to philosophy the discovery of the principle of the arch and the introduction of the use of metals. This eulogy was considered as an affront, and was taken up with proper spirit. Seneca vehemently disclaims these insulting compliments. Philosophy, according to him, has nothing to do with teaching men to rear arched roofs over their heads. The true philosopher does not care whether he has an arched roof or any roof. Philosophy has nothing to do with teaching men the uses of metals. She teaches us to be independent of all material substances, of all mechanical contrivances. The wise man lives according to nature. Instead of attempting to add to the physical comforts of his species, he regrets that his lot was not cast in that golden age when the human race had no protection against the cold but the skins of wild beasts, no screen from the sun but a cavern. To impute to such a man any share in the invention or improvement of a plough, a ship, or a mill, is an insult. In my own time, says Seneca, there have been inventions of this sort, transparent windows, tubes for diffusing warmth equally through all parts of a building, short-hand, which has been carried to such a perfection that a writer can keep pace with the most rapid speaker. But the inventing of such things is drudgery for the lowest slaves; philosophy lies deeper. It is not her office to teach men how to use their hands. The object of her lessons is to form the soul. Non est, inquam, instrumentorum ad usus necessarios opifex. If the non were left out, this last sentence would be no bad description of the Baconian philosophy, and would, indeed, very much resemble several expressions in the Novum Organum. We shall next be told, exclaims Seneca, that the first shoemaker was a philosopher. For our own part, if we are forced to make our choice between the first shoemaker and the author of the three books On Anger, we pronounce for the shoemaker. It may be worse to be angry than to be wet. But shoes have kept millions from being wet; and we doubt whether Seneca ever kept anybody from being angry."

"The ancient writers themselves afford us but little assistance. When they particularize, they are commonly trivial: when they would generalize, they become indistinct. An exception must, indeed, be made in favour of Aristotle. Both in analysis and in combination, that great man was without a rival. No philosopher has ever possessed, in an equal degree, the talent either of separating established systems into their primary elements, or of connecting detached phenomena in harmonious systems. He was the great fashioner of the intellectual chaos; he changed its darkness into light, and its discord into order. He brought to literary researches the same vigour and amplitude of mind to which both physical and metaphysical science are so greatly indebted. His fundamental principles of criticism are excellent. To cite only a single instance:—the doctrine which he established, that poetry is an imitative art, when justly understood, is to the critic what the compass is to the navigator. With it he may venture upon the most extensive excursions. Without it he must creep cautiously along the coast, or lose himself in a trackless expanse, and trust, at best, to the guidance of an occasional star. It is a discovery which changes a caprice into a science."

"The ascendency of the sacerdotal order was long the ascendency which naturally and properly belongs to intellectual superiority."

"The best historians of later times have been seduced from truth, not by their imagination, but by their reason. They far excel their predecessors in the art of deducing general principles from facts. But unhappily they have fallen into the error of distorting facts to suit general principles. They arrive at a theory from looking at some of the phenomena; and the remaining phenomena they strain or curtail to suit the theory. For this purpose it is not necessary that they should assert what is absolutely false; for all questions in morals and politics are questions of comparison and degree. Any proposition which does not involve a contradiction in terms may by possibility be true; and, if all the circumstances which raise a probability in its favour be stated and enforced, and those which lead to an opposite conclusion be omitted or lightly passed over, it may appear to be demonstrated. In every human character and transaction there is a mixture of good and evil: a little exaggeration, a little suppression, a judicious use of epithets, a watchful and searching scepticism with respect to the evidence on one side, a convenient credulity with respect to every report or tradition on the other, may easily make a saint of Laud, or a tyrant of Henry the Fourth."

"The assistance of the Ecclesiastical power had greatly contributed to the success of the Guelfs. That success would, however, have been a doubtful good, if its only effect had been to substitute a moral for a political servitude, and to exalt the Popes at the expense of the Cæsars. Happily the public mind of Italy had long contained the seeds of free opinions, which were now rapidly developed by the genial influence of free institutions. The people of that country had observed the whole machinery of the church, its saints and its miracles, its lofty pretensions and its splendid ceremonial, its worthless blessings and its harmless curses, too long and too closely to be duped. They stood behind the scenes on which others were gazing with childish awe and interest. They witnessed the arrangement of the pullies, and the manufacture of the thunders. They saw the natural faces and heard the natural voices of the actors. Distant nations looked on the Pope as the vicegerent of the Almighty, the oracle of the All-wise, the umpire from whose decisions, in the disputes either of theologians or of kings, no Christian ought to appeal. The Italians were acquainted with all the follies of his youth, and with all the dishonest arts by which he had attained power. They knew how often he had employed the keys of the church to release himself from the most sacred engagements, and its wealth to pamper his mistresses and nephews. The doctrines and rites of the established religion they treated with decent reverence. But, though they still called themselves Catholics, they had ceased to be Papists. Those spiritual arms which carried terror into the palaces and camps of the proudest sovereigns excited only contempt in the immediate neighbourhood of the Vatican. Alexander, when he commanded our Henry the Second to submit to the lash before the tomb of a rebellious subject, was himself an exile. The Romans, apprehending that he entertained designs against their liberties, had driven him from their city; and, though he solemnly promised to confine himself for the future to his spiritual functions, they still refused to readmit him."

"The best portraits are perhaps those in which there is a slight mixture of caricature."

"The best histories may sometimes be those in which a little of the exaggeration of fictitious narrative is judiciously employed. - Something is lost in accuracy, but much is gained in effect. - The fainter lines are neglected, but the great characteristic features are imprinted on the mind forever."

"The best proof that the religion of the people was of this mixed kind is furnished by the Drama of that age. No man would bring unpopular opinions prominently forward in a play intended for representation. And we may safely conclude that feelings and opinions which pervade the whole Dramatic literature of a generation are feelings and opinions of which the men of that generation generally partook. The greatest and most popular dramatists of the Elizabethan age treat religious subjects in a very remarkable manner. They speak respectfully of the fundamental doctrines of Christianity. But they speak neither like Catholics not like Protestants, but like persons who are wavering between the two systems, or who have made a system for themselves out of parts selected from both. They seem to hold some of the Romish rites and doctrines in high respect. They treat the vow of celibacy, for example, so tempting and, in later times, so common a subject for ribaldry, with mysterious reverence. Almost every member of a religious order whom they introduce is a holy and venerable man. We remember in their plays nothing resembling the coarse ridicule with which the Catholic religion and its ministers were assailed, two generations later, by dramatists who wished to please the multitude. We remember no Friar Dominic, no Father Foigard, among the characters drawn by those great poets. The scene at the close of the Knight of Malta might have been written by a fervent Catholic. Massinger shows a great fondness for ecclesiastics of the Romish Church, and has even gone so far as to bring a virtuous and interesting Jesuit on the stage. Ford, in that fine play which it is painful to read and scarcely decent to name, assigns a highly creditable part to the Friar. The partiality of Shakespeare for Friars is well known. In Hamlet, the Ghost complains that he died without extreme unction, and, in defiance of the article which condemns the doctrine of purgatory, declares that he is"

"The author of a great reformation is almost always unpopular in his own age. He generally passes his life in disquiet and danger. It is therefore for the interest of the human race that the memory of such men should be had in reverence, and that they should be supported against the scorn and hatred of their contemporaries by the hope of leaving a great and imperishable name. To go on the forlorn hope of truth is a service of peril. Who will undertake it, if it be not also a service of honour? It is easy enough, after the ramparts are carried, to find men to plant the flag on the highest tower. The difficulty is to find men who are ready to go first into the breach, and it would be bad policy indeed to insult their remains because they fell in the breach and did not live to penetrate to the citadel."

"The characteristic peculiarity of the Pilgrim’s Progress is that it is the only work of its kind which possesses a strong human interest. Other allegories only amuse the fancy. The allegory of Bunyan has been read by many thousands with tears. There are some good allegories in Johnson’s works, and some of still higher merit by Addison. In these performances there is, perhaps, as much wit and ingenuity as in the Pilgrim’s Progress. But the pleasure which is produced by the Vision of Mirza, the Vision of Theodore, the genealogy of Wit, or the contest between Rest and Labour, is exactly similar to the pleasure we derive from one of Cowley’s odes or from a canto of Hudibras. It is a pleasure which belongs wholly to the understanding, and in which the feelings have no part whatever. Nay, even Spenser himself, though assuredly one of the greatest poets that ever lived, could not succeed in the attempt to make allegory interesting. It was in vain that he lavished the riches of his mind on the House of Pride and the House of Temperance. One unpardonable fault, the fault of tediousness, pervades the whole of the Fairy Queen. We become sick of cardinal virtues and deadly sins, and long for the society of plain men and women. Of the persons who read the first canto, not one in ten reaches the end of the first book, and not one in a hundred perseveres to the end of the poem. Very few and very weary are those who are in at the death of the Blatant Beast. If the last six books, which are said to have been destroyed in Ireland, had been preserved, we doubt whether any heart less stout than that of a commentator would have held out to the end."

"The chief peculiarity of Bacon’s philosophy seems to us to have been this, that it aimed at things altogether different from those which his predecessors had proposed to themselves. This was his own opinion. Finis scientiarum, says he, a nemine adhuc bene positus est. And again, Omnium gravissimus error in deviatione ab ultimo doctrinarum fine consistit. Nec ipsa meta, says he elsewhere, adhuc ulli, quod sciam, mortalium posita est et defixa. The more carefully his works are examined, the more clearly, we think, it will appear that this is the real clue to his whole system, and that he used means different from those used by other philosophers, because he wished to arrive at an end altogether different from theirs."

"The church has many times been compared by divines to the ark of which we read in the book of Genesis; but never was the resemblance more perfect than during that evil time when she rode alone, amidst darkness and tempest, on the deluge beneath which all the great works of ancient power and wisdom lay entombed, bearing within her that feeble germ from which a second and more glorious civilization was to spring."

"The best codes extant, if malignantly criticized, will be found to furnish matter for censure in every page… the most copious and precise of human languages furnish but a very imperfect machinery to the legislator."

"The business of everybody is the business of nobody."

"The boast of the ancient philosophers was that their doctrine formed the minds of men to a high degree of wisdom and virtue. This was indeed the only practical good which the most celebrated of those teachers even pretended to effect; and undoubtedly, if they had effected this, they would have deserved far higher praise than if they had discovered the most salutary medicines or constructed the most powerful machines. But the truth is that, in those very matters in which alone they professed to do any good to mankind, in those very matters for the sake of which they neglected all the vulgar interests of mankind, they did nothing, or worse than nothing. They promised what was impracticable; they despised what was practicable; they filled the world with long words and long beards; and they left it as wicked and as ignorant as they found it."

"The cause may easily be assigned. This province of literature is a debatable land. It lies on the confines of two distinct territories. It is under the jurisdiction of two hostile powers; and, like other districts similarly situated, it is ill defined, ill cultivated, and ill regulated. Instead of being equally shared between its two rulers, the Reason and the Imagination, it falls alternately under the sole and absolute dominion of each. It is sometimes fiction. It is sometimes theory."

"The celebrity of the great classical writers is confined within no limits except those which separate civilized from savage man. Their works are the common property of every polished nation; they have furnished subjects for the painter, and models for the poet. In the minds of the educated classes throughout Europe, their names are indissolubly associated with the endearing recollections of childhood,—the old school-room,—the dog-eared grammar,—the first prize,—the tears so often shed and so quickly dried. So great is the veneration with which they are regarded, that even the editors and commentators who perform the lowest menial offices to their memory are considered, like the equerries and chamberlains of sovereign princes, as entitled to a high rank in the table of literary precedence. It is, therefore, somewhat singular that their productions should so rarely have been examined on just and philosophical principles of criticism."

"The character of the Italian statesman seems, at first sight, a collection of contradictions, a phantom as monstrous as the portress of hell in Milton, half divinity, half snake, majestic and beautiful above, grovelling and poisonous below. We see a man whose thoughts and words have no connection with each other, who never hesitates at an oath when he wishes to seduce, who never wants a pretext when he is inclined to betray. His cruelties spring, not from the heat of blood, or the insanity of uncontrolled power, but from deep and cool meditation. His passions, like well-trained troops, are impetuous by rule, and in their most headstrong fury never forget the discipline to which they have been accustomed. His whole soul is occupied with vast and complicated schemes of ambition; yet his aspect and language exhibit nothing but philosophical moderation. Hatred and revenge eat into his heart; yet every look is a cordial smile, every gesture a familiar caress. He never excites the suspicion of his adversaries by petty provocations. His purpose is disclosed only when it is accomplished. His face is unruffled, his speech is courteous, till vigilance is laid asleep, till a vital point is exposed, till a sure aim is taken; and then he strikes for the first and last time. Military courage, the boast of the sottish German, of the frivolous and prating Frenchman, of the romantic and arrogant Spaniard, he neither possesses nor values. He shuns danger, not because he is insensible to shame, but because, in the society in which he lives, timidity ceases to be shameful. To do an injury openly is, in his estimation, as wicked as to do it secretly, and far less profitable. With him the most honourable means are those which are the surest, the speediest, and the darkest. He cannot comprehend how a man should scruple to deceive those whom he does not scruple to destroy. He would think it madness to declare open hostilities against rivals whom he might stab in a friendly embrace or poison in a consecrated wafer."

"The characteristic faults of his style are so familiar to all our readers and have been so often burlesqued that it is almost superfluous to point them out. It is well known that he made less use than any other eminent writer of those strong plain words, Anglo-Saxon or Norman-French, of which the roots lie in the inmost depths of our language; and that he felt a vicious partiality for terms which, long after our own speech had been fixed, were borrowed from the Greek and Latin, and which, therefore, even when lawfully naturalized, must be considered as born aliens, not entitled to rank with the Queen’s English. His constant practice of padding out a sentence with useless epithets, till it became as stiff as the bust of an exquisite; his antithetical forms of expression, constantly employed even when there is no opposition in the ideas expressed; his big words wasted on little things; his harsh inversions, so widely different from those graceful and easy inversions which give variety, spirit, and sweetness to the expression of our great old writers; all these peculiarities have been imitated by his admirers and parodied by his assailants till the public has become sick of the subject."

"The conformation of his mind was such that whatever was little seemed to him great, and whatever was great seemed to him little."